Thoughts on the EU Digital Single Market

Some of you may have heard that about a week ago the European Film Commission announced the Digital Single Market Plan (which may also apply to TV licensing). Variety covered the story HERE and HERE.

You can read for yourself what the fuss is all about but essentially, the EU Film Commission’s plan is to combine the 28 European territories into a common market for digital goods, which would eliminate “geo-blocking,” which currently bars viewers from accessing content across borders – and yet purportedly, the plan would preserve the territory by territory sales model. Filmmakers, distributors, the guilds, et al argue that this proposal would only help global players / platforms such Netflix, Amazon and Google, which would benefit from a simpler way to distribute content across Europe.

The IFTA (International Film and Television Alliance) expressed concerns that this would enable only a few multinational companies to control film/tv financing. Variety noted that although politicians insist the idea of multi-territory licenses won’t be part of the plan, those in the content industry remain concerned about passive sales and portability and the impact on windows and marketing.

In the US, digital distribution is just hitting its stride and is also finally getting anchored properly in Europe. Now this idea would be one step closer to one-stop-digital shopping, or selling. Though allegedly that’s not in the plan – but it would sure be a step in that direction.

photo credit: movantia

Some are railing against it and warning against eliminating territory sales and windowing, hurting financing, and truncating important local marketing. Well, maybe and maybe not. I think it depends on the type of film or film industry player involved. A blockbuster studio hit or indie wide release sensation with international appeal may very likely be big enough to sell many territories, be big enough to warrant spending significant marketing money in each territory’s release, and be culturally malleable enough to lend itself to new marketing vision, materials, and strategies per market. On a related note, I remember hits such as Clueless being translated into different languages not just literally, but also culturally – modified for local appeal. That’s great, and possible, for some films.

But for most of the films we distribute at TFC and for the great majority on the festival circuit, they’ll be lucky to sell even 10 territories and many won’t sell even half that. Some sales in Europe are no minimum guarantee or a tiny minimum guarantee, just like it is State-side. Some films are financed per EU territory (government funding often) but that’s on the decline too.

The dilemma here about a digital single market in the EU recalls another common dilemma about whether to hold out for a worldwide Netflix sale or try to sell European TV or just EU period, one territory at a time. I’m not forgetting Asia or Africa but focusing on the more regular sales for American art house (not that selling Europe is an easy task for most American indies in any case). Sure, if you can sell the main Western European countries and a few Eastern ones that’s worthwhile taking into account. However, so often one does not sell those territories, or if one does, it’s for a pittance. Some sales can be for less than 5,000 Euros, or half that, or zero up front and not much more later. It’s not like the release then is career building either or a loss leader. It’s just buried or a drop in a big bucket.

In cases such as these, it makes little sense to hold off for a day that never comes or a day that really won’t do much for you. All this to say, I don’t think this proposal is one-size-fits all but I do think it’s worth trying on especially if you are in the petite section of the cinema aisle. If you are not sure how you measure up, ask around, comparison shop – see what films like yours (genre, style, topic, cast, festival premiere, budget, other names involved and other aspects) have done lately. Sometimes a worldwide Netflix deal may be the best thing that ever happened and I reckon that similarly, sometimes a plug and play EU digital deal (if this vision comes into fruition) will give you all that you could get in terms of accessing European audiences, while saving you money (in delivery and fees etc.). And then, get this, you can focus on direct-to-audience marketing – something few agents or distributors do much of anyway.

I kept this blog entry short as I stand by for more information out of Cannes and beyond and also await our TFC resident EU digital distribution guru Wendy Bernfeld (Advisory Board Member and co-author of the Selling Your Film Outside the U.S. case study book) to weigh in. In the meantime, I think it would be swell if one Cannes do digital in the EU all at once.

Please email me your thoughts to contactus [at] thefilmcollaborative.org or post them on our Facebook page so we can update this blog. We turned off comments here only because of the amount of spam we received in the past.

Orly Ravid May 14th, 2015

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution

Tags: Amazon, arthouse films, digital film distribution, Digital Single Market Plan, EU, Film commission, Google, independent film, International Film and Television Alliance, Netflix, Orly Ravid, Selling Your Film Outside the US, The Film Collaborative, Variety, Wendy Bernfeld

Uncertain state of distribution

At the recent Toronto International Film Festival, veteran independent film distributor Bob Berney gave a state of the industry address on distribution. TIFF was kind enough to make his keynote video available on Youtube (you can find it below), but here are some of the highlights if you don’t have 30 minutes to spare watching it.

-We’re in a chaotic, disruptive state right now with bigger studios making fewer, but massively budgeted films that involve huge risk.

-On the flip side, there are many more outlets now available to get a film into the market. The challenge as a producer is how to get revenue from these outlets in order to fund your next work.

-There are now well funded entities coming to major festivals and buying films without any real plan about how to release them.

-Open Road and Relativity Media are now distributing wide release theatrical films, sometimes as service deals (the production pays them to release, instead of the distribution company paying for rights).

-But platform release films, ones that start with opening in only 2-4 cities and then keep expanding their theatrical runs, are starting to have a tougher time finding a home, a company that will take them on. Fewer distributors are taking the traditional theatrical route and there are now more companies taking the day and date or VOD first route. Films that want a traditional release far outweigh the distribution companies that are willing to take on films for that kind of release.

-Berney believes that a theatrical release is the only way for a film to truly break out in the market in a big way.

-The bar for films that warrant having a large theatrical release has really been raised. The expense to release those films, even if using digital marketing, is big and the market is very competitive. Distributors who fund the marketing and distribution costs for those films are very wary about the ability to recoup.

-This summer there were many indie films that played in theaters against the studio blockbusters and did well. Boyhood, Magic in the Moonlight, Chef, Belle, Begin Again all surpassed expectations about how they would fare against the studio films. Berney believes it was because there was nothing else to see. Either superhero films or these and nothing in between. He guesses that the market could have taken even 4-5 more indie films this summer. People went to see some of those successful titles 2-3 times because there wasn’t much to choose from. Theatrical companies could have picked up more. The Fall season is crowded, but the summer could have used a few more releases.

-Because the deals are so different and the numbers come in sporadically, releasing VOD numbers is still not common.Also there aren’t very many success stories being reported from day and date or VOD only releases.

-Many European companies or smaller indie division within the studio units are not finding deals on their films very viable now. P&Ls for sales coming domestically (US) often have a 0 in the profit column. Sales can’t be counted on any more. Budgets have had to shrink accordingly because large deals aren’t happening so much any more.

Many of the newer players in the digital and VOD arena are constantly looking for content to fill their channels. Those films can play for a while until the audience gets more discerning.

-For any avenue chosen for distribution, the release has to create the feeling of an event to catch an audience’s attention. There is just too much in the market.

There is no one size fits all marketing and distribution plan. Each film needs to have its own plan handcrafted.

-Given the risk and expense, distributors are going to be much more discerning about what films they are passionate about and believe in before offering a deal.They want to be very sure there is an audience for a theatrical release before committing to such a deal.

-The Blu Ray market is still huge for certain types of films. Genre including family, horror, sci fi still do business on disc for Walmart and Redbox.

-Certain theaters are catching onto the idea of making the cinema an experience. Food, bigger seats, more varied showtimes, 4D seats are all increasing the feeling of an event in the cinema.

-Theaters are still resisting the idea of day and date. Regal and Cinemark chains are adamant about preserving the theatrical window. But AMC is more open to experimentation as long as the distributor will pay a 4 wall fee to rent their theaters. IFC and Magnolia own their own theater chains so they have been the most aggressive about trying Ultra VOD and day and date release. IFC buys about 50 films a year that they run though VOD and day and date releases.

-Due to regulation, Canada has not been able to experiment with this kind of releasing model yet.

-Berney still believes in the power of the theatrical release to affect an audience and that it is the best way to make a film break out.

-Netflix has been the savior for films that may not get a pay TV deal. Essentially, subscription VOD is on par with selling to HBO or Showtime. But Netflix takes far more films than those broadcasters.

-Social media advertising is allowing a more targeted and lower cost alternative to traditional advertising, plus providing much needed data on which to base strategic marketing decisions. Also these tools allow filmmakers to get clips, trailers, images etc to get out more widely for a lower cost and build pre release awareness that wasn’t even possible 10 years ago.

-There are just so many more opportunities now to get a film out, but it will take some time for the business side, the money making side, to catch up. That’s the uncertainty we are dealing with now.

Sheri Candler September 19th, 2014

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Theatrical

Tags: Bob Berney, digital film distribution, Picturehouse Films, State of Film Distribution, theatrical release, Toronto International Film Festival, VOD

Distribution preparation for independent filmmakers-Part 4 Deliverables

By Orly Ravid and Sheri Candler

In the past 3 posts, we have covered knowing the market BEFORE making your film, how to incorporate the festival circuit into your marketing and distribution efforts and understanding terms, the foreign market and release patterns. In this post, we will discuss the items that will be required by sales agents, distributors (primarily digital distributors) and even digital platforms (if you are thinking of selling directly to your audience with less middlemen) before a deal can be signed and the film can be distributed.

Know your deliverables

Distribution is an expensive and complicated process and all distribution contracts contain a list of required delivery items (often attached at the end of the document as an exhibit) in order to complete the agreement. Without the proper items, sales agents and distributors will not be interested in making a deal. Your film must have all proper paperwork, music licenses, and technical specifications in order and these delivery items will incur additional costs to your production. Make sure to include a separate budget for deliverables within the cost of your production.

US sales agents and distributors will require insurance covering errors and omissions (E&O) at minimum levels of $1,000,000 per occurrence, $3,000,000 in the aggregate with a deductible of $10,000, in force for three years. E&O insurance protects the producer and distributor (usually for the distributor’s catalog of films) against the impact of lawsuits arising from accusations of libel, slander, invasion of privacy, infringement of copyright etc and can cost the producer in the range of $3,000 to $5,000. E&O insurance is required BEFORE any deal is signed, not after, and can take 3-5 days to obtain if all rights and releases, a title report and music clearances can be supplied.

Digital aggregators in general do not require E&O insurance unless it is for cable VOD and Netflix (these do). However, they do require closed captioning (around $900), subtitling (if you intend to distribute in non English speaking territories, usually costs around $3 per minute) and a ratings certificate (if distributing in some foreign territories, prices vary according to run time and ratings board).

The production will need to supply a Quality Control (QC) report, preferably from a reputable encoding house. If you film fails QC for iTunes and other digital platforms, it can be costly to fix the problems with the file and it will lead to a delay of the film’s release. MANY problems can be found in the QC process so whatever you think you are saving by encoding yourself or via a less reputable company, you will more than make up for in having to redo it. The most common problems arise from duplicate frames or merged frames as a result of changing frame rates; audio dropouts or other audio problems; sync problems from closed caption or subtitling files.

Distributors will accept a master in Apple ProRes HQ 422 file on an external hard drive or HD Cam. By far, the digital drive is preferable to tape and unless your distributor specifically requests HD Cam, do not go to the expense of creating this. The master should NOT have pre roll advertising, website URLs, bars/tones/countdowns, ratings information, or release date information. For digital files, content must begin and end with at least one frame of black.

Other delivery items required by sales agents/distributors include: trailer (preferably 2 minutes) in the same aspect ratio as the film with no nudity or profanity; chapter points using the same time code as the master file; key art files as a layered PSD or EPS with minimum 2400 pixels wide at 300 dpi; at least 3-5 still images in high resolution (traditional distributors often require as many as 50 still images) and already approved by talent; DVD screeners; press kit which includes a synopsis, production notes, biographies for key players, director, producer, screenwriter, and credit list of both cast and crew; pdf of the original copyright document for the screenplay and the motion picture; IRS W-9 form or tax forms from governments of the licensor; music cue sheet and music licenses.

There are technical specifications that need to be met as far as the video and audio files. Most post production supervisors are aware of these. It is also not unheard of to be asked to supply 35 mm prints for foreign distribution if a theatrical release is desired or contractually obligated.

Sometimes if your film is considered a hot property, a distributor might be willing to create the delivery items at their expense in exchange for full recoupment and/or a greater cut of the revenues. But do not count on this. We have heard from many filmmakers who didn’t clear music rights for their films, assuming a distributor would take on this expense, and were sorely disappointed to find none would do that. If you can’t supply the delivery list, no agreement will be signed.

Sheri Candler July 23rd, 2014

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, International Sales

Tags: deliverables, Digital Distribution, digital film distribution, distribution contracts, film distribution, film distributors, independent film, Orly Ravid, preparing for film distribution, Sheri Candler

Sneak Peek #4: Carpe Diem for Indie Filmmakers in the Digital/VOD Sector

In this final excerpt from our upcoming edition of Selling Your Film Outside the U.S., Wendy Bernfeld of Amsterdam-based consultancy Rights Stuff talks about the current situation in Europe for independent film in the digital on demand landscape.

There have been many European platforms operating in the digital VOD space for the last 8 years or so, but recent changes to their consumer pricing structures and offerings that now include smaller foreign films, genre films and special interest fare as well as episodic content have contributed to robust growth. European consumers are now embracing transactional and subscription services , and in some cases ad-supported services, in addition to free TV, DVD and theatrical films. Many new services are being added to traditional broadcasters’ offerings and completely new companies have sprung up to take advantage of burgeoning consumer appetite for entertainment viewable anywhere, anytime and through any device they choose.

From Wendy Bernfeld’s chapter in the forthcoming Selling Your Film Outside the U.S.:

Snapshot

For the first decade or so of the dozen years that I’ve been working an agent, buyer, and seller in the international digital pay and VOD sector, few of the players, whether rights holders or platforms, actually made any serious money from VOD, and over the years, many platforms came and went.

However, the tables have turned significantly, and particularly for certain types of films such as mainstream theatrical features, TV shows and kids programming, VOD has been strengthening, first in English-language mainstream markets such as the United States, then in the United Kingdom, and now more recently across Europe and other foreign language international territories. While traditional revenues (eg DVD,) have dropped generally as much as 20% – 30%, VOD revenues—from cable, telecom, IPTV, etc.—have been growing, and, depending on the film and the circumstances, have sometimes not only filled that revenue gap, but exceeded it.

For smaller art house, festival, niche, or indie films, particularly overseas, though, VOD has not yet become as remunerative. This is gradually improving now in 2014 in Europe, but for these special gems, more effort for relatively less money is still required, particularly when the films do not have a recognizable/strong cast, major festival acclaim, or other wide exposure or marketing.

What type of film works and why?

Generally speaking, the telecoms and larger mainstream platforms prioritize mainstream films in English or in their local language. In Nordic and Benelux countries, and sometimes in France, platforms will accept subtitled versions, while others (like Germany, Spain, Italy, and Brazil) require local language dubs. However, some platforms, like Viewster, will accept films in English without dubbed or subtitled localized versions, and that becomes part of the deal-making process as well. This is the case, particularly for art house and festival films, where audiences are not surprised to see films in English without the availability of a localized version.

Of course, when approaching platforms in specific regions that buy indie, art house, and festival films, it is important to remember that they do tend to prioritize films in their own local language and by local filmmakers first. However, where there is no theatrical, TV exposure, or stars, but significant international festival acclaim, such as SXSW, IDFA, Berlinale, Sundance, or Tribeca, there is more appetite. We’ve also found that selling a thematic package or branded bundle under the brand of a festival, like IDFA, with whom we have worked (such as “Best of IDFA”) makes it more recognizable to consumers than the individual one-off films.

What does well: Younger (i.e., hip), drama, satire, action, futuristic, family and sci-fi themes tend to travel well, along with strong, universal, human-interest-themed docs that are faster-paced in style (like Occupy Wall Street, economic crisis, and environmental themes), rather than traditionally educational docs or those with a very local slant.

What does less well: World cinema or art house that is a bit too slow-moving or obscure, which usually finds more of a home in festival cinema environments or public TV than on commercial paid VOD services, as well as language/culture-specific humor, will not travel as well to VOD platforms.

Keep in mind that docs are widely represented in European free television, so it’s trickier to monetize one-offs in that sector, particularly on a pay-per-view basis. While SVOD or AVOD offerings (such as the European equivalents of Snagfilm.com in the US) do have some appetite, monetization is trickier, especially in the smaller, non-English regions. Very niche films such as horror, LGBTQ, etc. have their fan-based niche sites, and will be prominently positioned instead of buried there, but monetization is also more challenging for these niche films than for films whose topics are more generic, such as conspiracy, rom-com, thrillers, kids and sci-fi, which travel more easily, even in the art house sector.

However, platforms evolve, as do genres and trends in buying. Things go in waves. For example, some online platforms that were heavily active in buying indie and art house film have, at least for now, stocked up on feature films and docs. They are turning their sights to TV series in order to attract return audiences (hooked on sequential storytelling), justify continued monthly SVOD fees, and /or increase AVOD returns.

Attitude Shifts

One plus these days is that conventional film platform buyers can no longer sit back with the same historic attitudes to buying or pricing as before, as they’re no longer the “only game in town” and have to be more open in their programming and buying practices. But not only the platforms have to shift their attitude.

To really see the growth in audiences and revenues in the coming year or two, filmmakers (if dealing direct) and/or their representatives (sales agents, distributors, agents) must act quickly, and start to work together where possible, to seize timing opportunities, particularly around certain countries where VOD activities are heating up. Moreover, since non-exclusive VOD revenues are cumulative and incremental, they should also take the time to balance their strategies with traditional media buys, to build relationships, construct a longer-term pipeline, and maintain realistic revenue expectations.

This may require new approaches and initiatives, drawing on DIY and shared hybrid distribution, for example, when the traditional sales agent or distributor is not as well-versed in all the digital sector, but very strong in the other media—and vice versa. Joining forces, sharing rights, or at least activities and commissions is a great route to maximize potential for all concerned. One of our mantras here at Rights Stuff is “100% of nothing is nothing.” Rights holders sitting on the rights and not exploiting them fully do not put money in your pockets or theirs, or new audiences in front of your films.

Thus, new filmmaker roles are increasingly important. Instead of sitting back or abdicating to third parties, we find the more successful filmmakers and sales reps in VOD have to be quite active in social media marketing, audience engagement, and helping fans find their films once deals are done.

To learn more about the all the new service offerings available in Europe to the savvy producer or sales agent, read Wendy’s entire chapter in the new edition of Selling Your Film Outside the US when it is released later this month. If you haven’t read our previous edition of Selling Your Film, you can find it HERE.

Sheri Candler May 15th, 2014

Posted In: book, Digital Distribution, Distribution, International Sales

Tags: attitude shift, AVOD, digital film distribution, dubbing, Europe, Rights Stuff, self distribution, Selling Your Film Outside the U.S., subtitling, SVOD, VOD, Wendy Bernfeld

Considerations before starting distribution

Written by Orly Ravid and Sheri Candler

Now that the line up for feature films screening in Park City has been announced and the Berlinale is starting to reveal its selections, let’s turn our attention to the potential publicity and sales opportunities that await these films.

For those with lower budget, no-notable-names-involved films heading to Park City this January, we understand the excitement and hopefulness of the distribution offers you believe your film will attract, but we also want to implore you to be aware that not every film selected for a Park City screening will receive a significant distribution offer. There are a many other opportunities, perhaps BETTER opportunities, for your film to reach a global (not just domestic) audience, but if you aren’t prepared for both scenarios, the future of your film could be bleak.

For any other filmmaker whose film is NOT heading to Park City, this post will be vital.

Have you been a responsible filmmaker?

What does this mean? Time and again we at The Film Collaborative see filmmakers willingly, enthusiastically going into debt, either raising money from investors or credit cards or second mortgages (eek!) in order to bring their stories to life. But being a responsible filmmaker means before you started production, you clearly and realistically understood the market for your film. When you expect your film to: get TV sales, international sales, a decent Netflix fee, a theatrical release, a cable VOD/digital release, do you understand the decision making process involved in the buying of films for release? Do you understand how many middlemen may stand in the money chain before you get your share of the money to pay back financing? Was any research on this conducted BEFORE the production started? With the amount of information on sites like The Film Collaborative, MovieMaker, Filmmaker Magazine, IndieWire and hundreds of blogs online, there is no longer an excuse for not knowing the answers to most of these questions well before a production starts. This research is now your responsibility once you’ve taken investors’ money (even if the investor is yourself) and you want to pursue your distribution options. Always find out about middlemen before closing a deal, even for sales from a sales agent’s or distributor’s website, there may be middlemen involved that take a hefty chunk that reduces yours.

Where does your film fit in the marketplace?

Top festivals like Sundance, Berlin, Cannes, Toronto give a film the start of a pedigree, but if your film doesn’t have that, significant distribution offers from outside companies will be limited. Don’t compare the prospects for your film to previous films on its content or tone alone. If your film doesn’t have prestige, or names, or similar publicity coverage or a verifiable fanbase, it won’t have the same footprint in the market.

Your distribution strategy may be informed by the size of your email database, the size of the social media following of the film and its cast/crew, web traffic numbers and visitor locations from your website analytics, and the active word of mouth and publicity mentions happening around it. These are the elements that should help gauge your expectations about your film’s impact as well as its profitability. Guess what the impact is if you don’t have these things or they are small? Yeah…

Understand the difference between a Digital Aggregator and a Distributor?

Distributors take exclusive ownership of your film for an agreed upon time. Aggregators have direct relationships with digital platforms and often do not take an ownership stake. Sometimes distributors also have direct relationships with digital platforms, and so they themselves can also serve as an aggregator of sorts. However, sometimes it is necessary for a distributor to work with outside aggregators to access digital platforms.

Do understand that the digital platform takes a first dollar percentage from the gross revenue (typically 30%), then aggregators get to recoup their fees and expenses from what is passed through them, but there are some that only take a flat fee upfront and pass the rest of the revenue back. Then distributors will recoup any of their expenses and their fee percentage, then comes sales agents with their expenses and fees. And finally, the filmmaker will get his or her share. Many filmmakers and film investors do not understand this and wonder why money doesn’t flow back into their pockets just a few months after initial release. You guys are in the back of the line so hopefully, if you signed a distribution agreement, you received a nice advance payment. Think how many cuts are coming out of that $5.99 consumer rental price? How many thousands will you have to sell to see some money coming in?

Windowing.

If you do decide to release on your own, knowing how release windows work within the industry is beneficial. Though the time to sequence through each release window is getting shorter, you still need to pay attention to which sales window you open when, especially in the digital space. Anyone who has ever had a Netflix account knows that, as a consumer, you would rather watch a film using the Netflix subscription you have already paid for rather than shell out more cash to buy or rent a stream of the latest movies. But from a filmmaker/distributor’s perspective, this initial Transactional VOD (TVOD) window maximizes profits because, unlike a flat licensing fee deal from Netflix, the film gets a percentage of every transactional VOD purchase. So if you release your film on Netflix or another subscription service (SVOD) right away without being paid a significant fee for exclusivity, you are essentially giving the milk away. And when that happens, you can expect to see transactional purchases (a.k.a. demand for the cow) decrease.

Furthermore, subscription sites like Netflix will likely use numbers from transactional purchases to inform, at least in part, their decision as to whether or not to make an offer on a film in the first place. In other words, showing sales data, showing you have a real audience behind your film, is a key ingredient to getting on any platform where you need to ask permission to be on it. Netflix is not as interested in licensing independent film content as it once was. It is likely that if your film is not a strong performer theatrically, or via other transactional VOD sites, it may not garner a significant Netflix licensing fee or they may refuse to take it onto the platform.

Also be aware that some TV licensing will be contingent on holding back subscription releases for a period of time. If you think your film is a contender for a broadcast license, you may want to hold off on a subscription release until you’ve exhausted that avenue. Just don’t wait too long or the awareness you have raised for your film will die out.

Direct distribution from your website

Your website and social channels are global in their reach. Unless you are paid handsomely for all worldwide distribution rights to your film, your North American distributor should not run the channels where you connect with your audience; the audience you have spent months or years on your own to build and hope to continue to build. These channels can be used to sell access to your film far more profitably for you than going through several middlemen.

Many low budget American films are not good candidates for international sales because the audience worldwide isn’t going to be big enough to appeal to various international distributors. Rather than give your rights to a sales agent for years just to see what they can do, think seriously about selling to global audiences from your own website and from sites such as Vimeo, Youtube, and iTunes. In agreements we make with distributors for our members, we negotiate the ability to sell worldwide to audiences directly off of a website without geo-blocking unsold territories. If you are negotiating agreements with other distributors, the right to sell directly can be extremely beneficial to carve out. If you do happen to sell your film in certain international territories, it is wise to also make sure you do not distribute on your site in a way that will conflict with any worldwide street dates and any other distribution holdbacks or windowing that may be required per your distribution contract.

You can sell DVDs, merchandise, downloads and streaming off your own site with the added benefit of collecting contact email addresses for use throughout your filmmaking career. Above all, don’t hold out for distribution opportunities that may not come when publicity and marketing is happening. So many times we are contacted by filmmakers who insist on spending a year or more on the festival circuit with no significant distribution offers in sight and they are wasting their revenue potential by holding back on their own distribution efforts. You can play festivals AND sell your films at the same time. Many regional fests no longer have a policy against films with digital distribution in place. When the publicity and awareness is happening, that’s the time to release.

Festival distribution is a thing

Did you know that festivals will pay screening fees to include your film in their program? It’s true! But there is a caveat. Your film must have some sort of value to festival programmers. How does a film have value? By premiering at a world class festival (Sundance, Berlin, SXSW etc or at a prestige niche festival) or having notable name cast. Those are things that other festivals prize and are willing to pay for.

You should try to carve out your own festival distribution efforts if a sales or distribution agreement is presented. That way you will see these festival screening fees and immediately start receiving revenue. Our colleagues, Jeffrey Winter and Bryan Glick, typically handle festival distribution for members of The Film Collaborative without needing to take ownership rights over the film (unlike a sales agent). TFC shares in a percentage of the screening fee and that is the only way we make money from festival distribution. No upfront costs, no ownership stake.

Deliverables

This is an expense that many new filmmakers are unfamiliar with and without the proper delivery items, sales agents and distributors will not be able/interested in distributing your film. You may also find that even digital platforms will demand some deliverables. At TFC (as well as with any sales agent/distributor), we require E&O insurance with a minimum coverage of $1,000,000 per occurrence, $3,000,000 in the aggregate, in force for a term of three years. The cost to purchase this insurance is approximately $3000-$5000. Also, a Closed Captioning file is required for all U.S. titles on iTunes. The cost can be upwards of $900 to provide this file. Additionally, many territories (such as UK, Australia, New Zealand and others) are now requiring official ratings from that territory’s film classification board, the cost of which can add up if you plan to make your film available via iTunes globally. For distributors, closed captioning and foreign ratings are recoupable expenses that they pay for upfront, but if you are self distributing through an aggregator service, this expense is on you upfront.

You may also be asked to submit delivery items to a sales agent or a distributor such as a HD Video Master, a NTSC Digi- Beta Cam down conversion and a full length NTSC Digi-Beta Pan & Scan tape all accompanied by a full Quality Control report, stereo audio on tracks 1&2, the M&E mix on tracks 3&4 and these may cost $2000-$5000 depending on the post house you use. If your tapes fail QC and you need to go back and fix anything, the cost could escalate upwards of $15,000. Then there are the creative deliverables such as still photography, key art digital files if they exist, electronic press kit if it exists or the video footage to be assembled into one, the trailer files if they exist. Also, all talent contracts and releases, music licenses and cue sheets, chain of title, MPAA rating if available etc.

Distribution is a complicated and expensive process. Be sure you have not completely raided your production budget or allocated a separate budget (much smarter!) in order to distribute directly to your audience and for the delivery items that will be needed if you do sign an agreement with another distribution entity. Also, seek guidance, preferably from an entity that is not going to take an ownership stake in the film for all future revenue over a long period of time.

For those headed to Park City, good luck with your prospects. TFC will be on the ground so keep up with our Tweets and Facebook posts. If the offers aren’t what you envisioned for your film, be ready to mobilize your own distribution efforts.

Sheri Candler December 19th, 2013

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution

Tags: Berlin, cable VOD, digital aggregators, digital distributors, digital film distribution, independent film distribution, Netflix, Orly Ravid, Park City, release windows, Sheri Candler, Sundance, The Film Collaborative

The Audacity of Hope: A Window into the Minds of Filmmakers at Independent Film Week

Next week (September 15 – 19) marks IFP’s annual “Independent FIlm Week” in NYC, herein dozens of fresh-faced and “emerging” filmmakers will once again pitch their shiny new projects in various states of development to jaded Industry executives who believe they’ve seen and heard it all.

Most of you reading this already know that pitching a film in development can be difficult, frustrating work…often because the passion and clarity of your filmmaking vision is often countered by the cloudy cynicism of those who are first hearing about your project. After all, we all know that for every IFP Week success story (and there are many including Benh Zeitlin’s Beasts of the Southern Wild, Courtney Hunt’s Frozen River, Dee Rees’ Pariah, Lauren Greenfield’s The Queen of Versailles, Stacie Passon’s Concussion etc…), there are many, many more films in development that either never get made or never find their way into significant distribution or, god forbid, profit mode.

So what keeps filmmaker’s coming back year after year to events like this? Well, the simple answer is “hope” of course….hope, belief, a passion for storytelling, the conviction that a good story can change the world, and the pure excitement of the possibilities of the unknown.

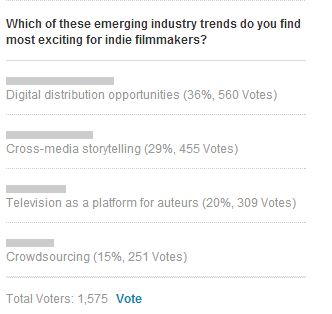

Which is why I found a recent poll hosted on IFP’s Independent Film Week website [right sidebar of the page] so interesting and so telling….in part because the result of the poll runs so counter to my own feelings on the state of independent film distribution.

On its site, IFP asks the following question:

Before you view results so far, answer the question….Which excites YOU the most? Now go vote and see what everyone else said.

** SPOILER ALERT — Do Not Read Forward Until You’ve Actually Voted**

What I find so curious about this is in my role as a independent film distribution educator at The Film Collaborative, I would have voted exactly the other way.

I suspect that a key factor in IFP Filmmakers voting differently than I has something to do with a factor I identified earlier, which I called “the pure excitement of the possibilities of the unknown.” I’m guessing most filmmakers called the thing most “exciting” that they knew the least about. After all 1) “Crowdsourcing” seems familiar to most right now, and therefore almost routine to today’s filmmakers….no matter how amazing the results often are. 2) “Television As a Platform for Auteurs” is also as familiar as clicking on the HBO GO App….even despite the fact that truly independent voices like Lena Dunham have used the platform to become household names. 3) Cross Media Story Telling remains a huge mystery for most filmmakers outside the genre sci-fi and horror realms….especially for independent narrative filmmakers making art house character-driven films. It should be noted that most documentary filmmakers understand it at least a little better. And 4) Digital Distribution Opportunities…of course this is the big one. The Wild West. The place where anything and everything seems possible…even if the evidence proclaiming its success for independents STILL isn’t in, even this many years after we’ve started talking about it.

But still we hope.

From our POV at The Film Collaborative, we see a lot of sales reports of exactly how well our truly independent films are performing on digital platforms….and for the most part I can tell you the results aren’t exactly exciting. Most upsetting is the feeling (and the data to back it) that major digital distribution platforms like Cable VOD, Netflix, iTunes etc are actually increasing the long-tail for STUDIO films, and leaving even less room than before for unknown independents. Yes, of course there are exceptions — for example our TFC member Jonathan Lisecki’s Gayby soared to the top of iTunes during Gay Pride week in June, hitting #1 on iTunes’ indie charts, #3 on their comedy charts, and #5 overall—above such movie-star-studded studio releases as Silver Linings Playbook and Django Unchained. But we all know the saying that the exception can prove the rule.

Yes, more independent film than ever is available on digital platforms, but the marketing conundrums posed by the glut of available content is often making it even harder than ever to get noticed and turn a profit. While Gayby benefited from some clever Pride Week-themed promotions that a major player like iTunes can engineer, this is not easily replicated by individual filmmakers.

For further discussion of the state of independent digital distribution, I queried my colleague Orly Ravid, TFC’s in house guru of the digital distro space. Here’s how she put it:

“I think the word ‘exciting’ is dangerous if filmmakers do not realize that platforms do not sell films, filmmakers / films do.

What *is* exciting is the *access*.

The flip side of that, however, is the decline in inflation of value that happened as a result of middle men competing for films and not knowing for sure how they would perform.

What I mean by that is, what once drove bigger / more deals in the past, is much less present today. I’m leaving theatrical out of this discussion because the point is to compare ‘home entertainment.’

In the past, a distributor would predict what the video stores would buy. Video stores bought, in advance often, based on what they thought would sell and rent well. Sure there were returns but, in general, there was a lot of business done that was based on expectation, not necessarily reality. Money flowed between middle men and distributors and stores etc… and down to the sellers of films. Now, the EXCITING trend is that anyone can distribute one’s film digitally and access a worldwide audience. There are flat fee and low commission services to access key mainstream platforms and also great developing DIY services.

The problem is, that since anyone can do this, so many do it. An abundance of choice and less marketing real estate to compel consumption. Additionally, there is so much less of money changing hands because of anticipation or expectation. Your film either performs on the platforms or on your site or Facebook page, or it does not. Apple does not pay up front. Netflix pays a fee sort of like TV stations do, but only based on solid information regarding demand. And Cable VOD is as marquee-driven and not thriving for the small film as ever.

The increasing need to actually prove your concept is going to put pressure on whomever is willing to take on the marketing. And if no one is, most films under the impact of no marketing will, most likely, make almost no impact. So it’s exciting but deceptive. The developments in digital distribution have given more power to filmmakers not to be at the mercy of gatekeepers. However, even if you can get into key digital stores, you will only reach as many people and make as much money as you have marketed for or authentically connected to.”

Now, don’t we all feel excited? Well maybe that’s not exactly the word….but I would still say “hopeful.”

To further lighten the mood, I’d like to add a word or two about my choice for the emerging trend I find most exciting — and that is crowdsourcing. This term is meant to encompass all activities that include the crowd–crowdfunding, soliciting help from the crowd in regard to time or talent in order to make work, or distributing with the crowd’s help. Primarily, I am going to discuss it in terms of raising money.

Call me old-fashioned, but I still remember the day (like a couple of years ago) when raising the money to make a film or distribute it was by far the hardest part of the equation. If filmmakers work within ultra-realistic budget parameters, crowd-sourcing can and usually does take a huge role in lessening the financial burdens these days. The fact is, with an excellently conceived, planned and executed crowdsourcing campaign, the money is now there for the taking…as long as the filmmaker’s vision is strong enough. No longer is the cloudy cynicism of Industry gatekeepers the key factor in raising money….or even the maximum limit on your credit cards.

I’m not implying that crowdsourcing makes it easy to raise the money….to do it right is a whole job unto itself, and much hard work is involved. But these factors are within a filmmaker’s own control, and by setting realistic goals and working hard towards them, the desired result is achieved with a startling success rate. And it makes the whole money-raising part seem a lot less like gambling than it used to….and you usually don’t have to pay that money back.

To me, that is nothing short of miraculous. And the fact that it is democratic / populist in philosophical nature, and tends to favor films with a strong social message truly thrills me. Less thrilling is the trend towards celebrities crowdsourcing for their pet projects (not going to name names here), but I don’t subscribe to a zero-sum market theory here which will leave the rest of us fighting over the crumbs….so if well-known filmmakers need to use their “brand” to create the films they are most passionate about…I won’t bash them for it.

In fact, there is something about this “brand-oriented” approach to crowdsourcing that may be the MOST instructive “emerging trend” that today’s IFP filmmakers should be paying attention to…as a way to possibly tie digital distribution possibilities directly to the the lessons of crowdsourcing. The problem with digital distribution is the “tree-falls-in-the-forest” phenomenon….i.e. you can put a film on a digital platform, but no-one will know it exists. But crowdsourcing uses the exact opposite principal….it creates FANS of your work who are so moved by your work that they want to give you MONEY.

So, what if you could bring your crowdsourcing community all the way through to digital distribution, where they can be the first audience for your film when it is released? This end-to-end digital solution is really bursting with opportunity…although I’ll admit right here that the work involved is daunting, especially for a filmmaker who just wants to make films.

As a result, a host of new services and platforms are emerging to explore this trend, for example Chill. The idea behind this platform (and others) is promising in that it encourages a “social window” to find and engage your audience before your traditional digital window. Chill can service just the social window, or you can choose also to have them service the traditional digital window. Crowdfunding integration is also built in, which offers you a way to service your obligations to your Kickstarter or Indiegogo backers. They also launched “Insider Access” recently, which helps bridge the window between the end of the Kickstarter campaign and the release.

Perhaps it is not surprising therefore, that in fact, the most intriguing of all would be a way to make all of the “emerging trends” work together to create a new integrated whole. I can’t picture what that looks like just yet…and I guess that is what makes it all part of the “excitement of the possibilities of the unknown.”

Jeffrey Winter will be attending IFP Week as a panelist and participant in the Meet the Decision Makers Artists Services sessions.

Jeffrey Winter September 12th, 2013

Posted In: crowdfunding, Digital Distribution, DIY, Film Festivals, iTunes, Long Tail & Glut of Content, Marketing

Tags: cable VOD, cross media storytelling, crowdfunding, Crowdsourcing, digital film distribution, Gayby, hope, IFP, Independent Film Week, iTunes, Jonathan Lisecki, Netflix, Orly Ravid, The Film Collaborative

The Independent’s Guide to Film Exhibition and Delivery 2013

2012 was a profound and often painful year in terms of the rapid technological change impacting the delivery and exhibition of independent film.

2012 was the year we wrapped our heads around the idea that there are virtually no more 35mm projectors in theatrical multiplexes, and that the Digital Cinema Package (DCP) has taken its throne as king – right alongside its wicked little stepchild, the BluRay.

2012 was the year it became clear that the delivery and exhibition formats we’ve been relying on for the last few years (especially HDCAMs) are no longer sufficient, and that in order to keep pace with the marketplace, we must now embrace the next round of digital evolution.

There are many filmmakers who will now want to stop reading, thinking “ughh, techie-nerd speak, that’s for my editor and post-supervisor to worry about.” You may believe you are first and foremost an artist and a storyteller, but in today’s world your paintbrushes are digital capturing devices, and your canvas is the wide array of digital delivery systems available to you. To shield yourself from the reality of how technological change will affect your final product is to face sobering and expensive complications later that will dramatically impact your ability to exhibit your film in today’s venues (including film festivals, theatres, and other public screening venues), as well as meet the needs of distributors and platforms worldwide.

And, so, for this New Year, I offer this “Guide to Exhibition & Delivery 2013,” a quasi-techie survival guide to the landscape of technological change in the foreseeable future, keeping in mind that this may all look very different again when we revisit this just a year from now…

What changed in 2012?

As 2012 began, major film festivals worldwide had largely coalesced around the HDCAM (despite slight but annoying differences in North American and European frame rates); and distributors and direct-to-consumer platforms were largely satisfied with HDCAM or Quicktime file-format deliveries, although varying platforms required different file specifications which could prove difficult for independent filmmakers to match (most notably iTunes). In addition, a large sector of the distribution landscape, including small film festivals, educational institutions (universities, museums, etc), and even small art house theaters remained content to screen on DVD and other standard-definition formats. The high-definition BluRay – with its beautiful image quality and powerful economic edge in terms of cost of production, shipping, and deck rental — was also emerging as an alternative to HDCAM, Digibeta, and DVD exhibition, despite the warnings by the techie/quality-control class that BluRays would be perilously unreliable in a live exhibition context.

But behind the scenes, the engine of the corporate machine driving studio film distribution was already fast at work driving top-down change. Finally, after years of financial impasse as to how to equip the theatrical network with digital projectors, the multinational Sony / Technicolor / Christie Digital / Cinedigms of the world had immersed themselves fully in the space and converted the North American multiplex system to a digital, file-based projection standard set by DCI LLC (a consortium of the major studios) – saving the studios immeasurably in print and shipping costs, as well as standardizing and upgrading image quality and providing additional security against piracy. This standardization as defined by the DCI studio consortium had already been growing in Europe for years before the North American market caught up, and became known worldwide as the DCP (Digital Cinema Package).

Once the largest technological and exhibition purveyors worldwide had made their move towards standardizing film exhibition, the writing was already on the wall, although it would take several more months to make its impact fully felt in the independent world.

What is a DCP?

A Digital Cinema Package (DCP) is a collection of digital files used to store and convey digital cinema audio, image, and data streams. General practice adopts a file structure that is organized into a number of Material eXchange Format (MXF) files, which are separately used to store audio and video streams, and auxiliary index files in XML format. The MXF files contain streams that are compressed, encoded, and (usually) encrypted, in order to reduce the huge amount of required storage and to protect from unauthorized use (if desired). The image part is JPEG 2000 compressed, whereas the audio part is linear PCM. The (optional) adopted encryption standard is AES 128 bit in CBC mode.

The most common DCP delivery method uses a specialty hard disk (most commonly the CRU DX115) designed specifically for digital cinema servers to ingest the files. These hard drives were originally designed for military use but have since been adopted by digital cinema for their hard wearing and reliable characteristics. The hard drives are usually formatted in the Linux EXT2 or EXT3 format as D-Cinema servers are typically Linux based and are required to have read support for these file systems.

Hard drive units are normally hired from a digital cinema encoding company, sometimes (in the case of studios pictures) in quantities of thousands. The drives are delivered via express courier to the exhibition site. Other, less common, methods adopt a full digital delivery, using either dedicated satellite links or high speed Internet connections.

In order to protect against the piracy fears that often surround digital distribution, DCP typically apply AES encryption to all MXF files. The encryption keys are generated and transmitted via a KDM (Key Delivery Message) to the projection site. KDMs are XML files containing encryption keys that can be used only by the destination device. A KDM is associated to each playlist and defines the start and stop times of validity for the projection of that particular feature.

As a result of all the standardized formatting and encryption features, the DCP offers a quality product generally considered to be superior to 35mm (while simultaneously conforming to the beloved 24 fps rate of 35mm), and a product that can theoretically be shared around the world with less variables and greater reliability than most formats (since 35mm) to date. Given the confusing array of formats facing filmmakers in recent years, there are many ways that the DCP revolution seems a singular advancement worth applauding, and at least on the surface, as a clear way forward for film exhibition and delivery for years to come.

So what’s wrong with that?… DCP survival for independents.

Before running out to master your film on DCP now, it is important to consider at least the following mitigating factors, 1) the utility of the format, 2) the price of DCP (including the hidden costs), and 3) the newness of the format and the inherent dangers associated with new formats, and 4) the ways that DCP will not save you from the usual headaches of delivery, and is in many ways an existential threat to independent film distribution as we currently know it.

With regards to the utility of DCP, remember that it is currently a cinema exhibition product, not a format that will be useful for delivery to distributors, consumer-facing platforms, DVD replicators etc. So, obviously you must be quite sure that you have actually made a theatrical film, and by this I mean theatrical in the broadest sense possible…i.e. will your film actually find life in cinematic venues including top film festivals etc. Following the industry at large, film festivals around the globe are in hyper-drive to convert to DCP as their preferred or even exclusive format. Going into the film festival circuit in 2013 and forward in any mainstream/meaningful way without a DCP…especially for narrative features….will be challenging to say the least (although likely still doable if you are willing to forfeit some bookings and some quality controls). But if you aren’t sure yet if your film will actually command significant public exhibition at major festivals and theatrical venues, you probably shouldn’t dive into the pool just yet.

Not surprisingly, the largest concern to independents is the issue of price. While nowhere near to the old cost of 35mm, DCP does represent a significant increase in mastering cost over HDCAM, Digibeta etc. In researching this article, most labs quoted me a rate of approx. $2,000 for a ninety minute feature, plus additional costs for the specialty hard drives and cables etc. that put the total closer to $2,500 +. As is the case with most digital products, however, it appears the costs are already headed downward as more and more independent labs get into the space, and it seems reasonable to assume that the price-conscious shopper should be able to find $1,500 and even $1,000 DCPs in the near future (especially with in-house lab deals working for specific distribution companies).

Following the initial mastering costs, the files can be replicated onto additional custom hard drives for prices in the range of $300 – $400, which is at least relatively commensurate with HDCAM replication. This replication process is controversial however — there is no doubt that one can decide to skirt this cost by transferring the files to standard over-the-counter hard drives that run in the range of $100 (we have already distributed one film theatrically and successfully using standard, low-price hard drives). But many labs and exhibitors will warn you against this, telling you that using non-custom hard drives and cables increase the chance that the server at the venue will not be able read the files, and therefore unable to ingest and project the film when it counts most.

In fact, to avoid these potential compatibility issues with differing hard drives, cables etc, some exhibitors (most notably Landmark) are requiring distributors and filmmakers to use specific labs who encode all their content, which perilously puts the modes of production in the hands of the few, and may ultimately keep the cost artificially high. And while indeed there are many reasons to fear compatibility issues between DCP and server (I have already heard of/attended numerous screenings cancelled or delayed in 2012 due to DCP compatibility issues), it is in fact this level of lab and exhibitor control over the product that makes me very nervous about the future of DCP in the independent distribution space.

The most dramatic example of the DCP “threat” to indie distribution is the emergence of the onerous VPF (Virtual Projection Fee) that is now being applied at many (if not most) mainstream theatrical venues (including art house chains like Landmark). The VPF is an $800 – $1,000 per screen fee that is added to the distributor or DIY filmmaker’s distribution costs, either leveraged against the film rental or added as a an additional cost to the four-wall. This fee may go down after 20 or so screens, or in a films 3rd or 4th week of adding cities, but otherwise it is largely a fixed fee tacked against the already low profits of most independent theatricals today.

The reason for the fee stems from the fact that the projection companies mentioned earlier (Sony, Christie Digital, etc.) in fact financed the introduction of the digital projectors into the theaters, so the VPF fees largely go towards the recoupment of their investments. But, even once these initial investments have been paid off, it is likely that the VPF will continue as a valuable money-maker for the tech companies, and is not likely to disappear any time soon. And in this age where the financial model of independent theatrical distribution hangs so perilously on a knife’s edge anyway, the VPF almost feels like a coup-de-grace dooming small theatrical releases from the get-go.

Another troublesome aspect of DCP distribution is the very encryption technology that was meant to make the product safer from piracy, but also adds an additional level of bureaucracy and cost that most independents cannot realistically afford. The encryption keys (known as KDMs) are controlled entirely by large labs like Technicolor, and are transferred directly from companies like Technicolor to specific theaters within specific venues for limited windows of time. Anyone who has been involved with the free-wheeling nature of independent distribution knows that relying on large labs for print trafficking and shepherding is expensive and time-consuming, and cuts deeply into already marginal profits. And if you are creating DCPs for film festival distribution, the very idea that a single theater in a far-flung locale must rely on a 3rd party lab to get a specific KDM code for its screenings seems akin to courting disaster to me. Indeed, I know several independent festivals that are not accepting DCPs at this point, simply because they refuse to subject themselves to the whims of the studio KDMs.

For the above reasons and more, I’ve encountered several Industry folks who have been so blunt as to tell me, “DCPs were invented to put independents out of business.”

While I’m not quite ready to go there, I will add that the most pernicious aspect of DCP introduction into the market in my opinion is the way that they are already creating a new two-tier distribution market between those larger festivals and venues that can afford DCP projection and those mid-sized and smaller than cannot and perhaps never will be (given the prohibitive cost of the projector technology). As such, DCP does not replace the HDCAMs, Digibetas etc of old, it is rather an additional format that independents must contend with – good in some situations, useless in others – and yet an additional cost to add to your contemporary distribution budget.

As a result of the emerging two-tiered system; with DCP for the better-funded venues and alternatives for the smaller, less-funded; there remains a gaping hole in the contemporary exhibition system which is increasingly filled by the most seductive and problematic format available to independent filmmakers today – and by that of course I mean the BluRay.

The bastard step-child, the BluRay.

Yes I used the word bastard deliberately and with purpose, because the BluRay is the most enticing and simultaneously cruel of the contemporary exhibition/delivery formats.

For independent filmmakers and exhibitors (including theaters, festivals, and other venues) alike, the BluRay seems at first glance an ideal option – inexpensive to produce and inexpensive to ship – to go along with inexpensive players and projectors that can be bought at consumer-level prices. And the quality of both image and sound is usually shockingly good – usually commensurate with the best HDCAM ever had to offer.

As such, the economics of film exhibition have lead to an explosion of BluRay use in 2012, with the format beginning the year as an enticing alternative but quickly emerging as the mainstay of mid-to small size venues in both North America and Europe. But just as quickly as BluRay has emerged, a truism about today’s BluRay technology has become painfully clear – it exists at consumer-level pricing because it is not a professional product – and its failure rate in live exhibition context is dangerously (if not outright unacceptably) high.

Consider the following: In recent years prior to 2012, it was nearly unheard of that a booking at a theater or festival should need to be cancelled or delayed due to exhibition format failure…because formats like 35mm or BetaSP or Digibeta or HDCAM were nothing if not reliable. But suddenly in 2012, the cancelled screening, or the delay mid-screening, or the skipping and freezing of a disc mid-screening became commonplace. To our dismay, it has become normal in 2012 to stop a screening mid-stream for a few moments to switch to a back-up DVD to replace a faulty BluRay. In our haste to transform to the miracles that BluRays seemed to afford us, a variable of chaos and unreliability has been introduced…and as yet there are no easy answers to this conundrum anywhere in sight.

There are numerous factors that account for BluRay unreliability – too many in fact to list in their entirety in this posting. There are many compression issues – resulting in variable gigbyte-per-layer Blurays from 25GB per layer to dual layer to triple layer to quadruple layer discs etc. These are profoundly complicated by player-compatibilty issues – meaning that many BluRays that play perfectly in one player will not even load in another. There are also significant regional differences between BluRay formats – similar but even more complicated than the old PAL vs. NTSC coding schemes. Layer onto this the fact that BluRays are fragile and scratch easily and do not traffic well and are easily lost, and we have arrived upon a formula for delivery chaos, to say the least.

As of today, as we go to print on this post, an uneasy truce on the proper protocol of BluRay delivery seems to be emerging Industry wide…for the moment at least. If you are going to screen your film on BluRay, you must provide at least a DVD back-up in case something goes wrong. Ideally, you should provide 2 BluRays, each of which have been tested, and a DVD back up as well. You still might experience screenings where your film will be stopped mid-stream, and replaced by one of the back-ups, but at least you won’t likely face the humiliation of a fully cancelled screening.

It’s hard to call this progress….but for the moment this is the price we are paying for digital evolution. The irony is…if BluRays were just a little cheaper than they currently are (generally somewhere between $10 – $40 each following an initial $300 – $500 investment), we might all dispense with attempting to traffic them completely, and just provide pristine BluRays for each screening (with somewhat less propensity for failure). This might solve some of the trafficking and delicacy issues, but this does not seem realistic for most filmmakers just yet, especially as so many other factors still come to bear. To be clear, the issues of BluRay unreliability are far more complex than just scratches and trafficking issues, so providing pristine BluRays to each booking will not solve all the issues, and DVD backup will still be necessary for the foreseeable future.

The further irony here is that DVDs, long since seen as less reliable although in all other ways preferable over the old VHS format, have now become the stalwart back-up to the BluRay…for even the traditional 5% failure rate for the DVDR format have become models of reliability as compared with the mercurial nature of the contemporary BluRay. Thankfully, today’s DVDs rarely fail in a pinch…

Where do we go from here?

When finishing a film in early 2013, filmmakers are now faced with the question of what delivery formats to create to meet delivery and exhibition demands. However, given the volatility of the current delivery landscape, it may be actually best to NOT commit to any particular exhibition format, and instead finish your film in a digital (hard-drive) format that you can keep as a master at a trusted lab for future needs down the road. It is advisable to have your film in the most flexible format possible, until you are forced by circumstance to deliver a specific format for a specific purpose.

The most flexible and useful format to initiate most exhibition/delivery formats at the moment is the Apple ProRes 422 digital file. Apple ProRes is a line of intermediate codecs, which means they are intended for use during video editing, and not for practical end-user viewing. The benefit of an intermediate codec is that it retains higher quality than end-user codecs while still requiring much less expensive disk systems compared to uncompressed video. It is comparable to Avid’s DNxHD codec or CineForm who offer similar bitrates which are also intended to be used as intermediate codecs. ProRes 422 is a DCT based intra-frame-only codec and is therefore simpler to decode than distribution-oriented formats like H.264.

From your ProRes 422 file, you will be able to make any format you need for today’s distribution landscape….from DCPs and BluRays to HDCAMs and any digital files you may need for platform distribution worldwide. This makes it ideal as an intermediary format as you consider your next steps forward.

In 2013, the needs of your exhibition formats and delivery formats will likely be determined by how successful your film turns out to be. If your film turns out to be truly theatrical, you will likely need a combination of DCPs and HDCAMs and BluRays to meet the demands. But if your film turns out to have limited public exhibition applications, then perhaps a mix of BluRays, DVDs, and digital files may be all you need. Rather than make those decisions in advance, we recommend you pursue a delivery strategy that lets the marketplace make those decisions for you.

In 2013, these delivery strategies will be impacted by the rate of technological development, just as they were in 2012. For the time being, it seems to wisest to counsel that we not get ahead of ourselves, and deliver films as a ProRes 422 file available for quick turnaround at a trusted lab with multi-format output capacity. From there, we can be assured of the ability to take our opportunities whenever and wherever they may lead us.

Jeffrey Winter January 7th, 2013

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Theatrical

Tags: BluRay, DCP, Digibeta, Digital Cinema Package, digital delivery systems for film, digital film distribution, file formats for film, HDCam, independent cinema, independent film, independent film distribution, Jeffrey Winter, KDM, theatrical distribution