How did the Sundance documentaries 2012 fare?

Sundance is the preeminent film festival in the world to premiere documentaries. In fact, 10 of the 15 films shortlisted for the 2013 Oscar for best documentary had their debut at the 2012 festival and 4 of the 5 nominees world premiered at the festival.

11 of the documentaries have grossed over $100,000 at the North American box office (with a 12th all but guaranteed). That is just barely less than the number of docs from TIFF, Cannes, Berlin, SXSW, and Tribeca combined that were able to cross the same threshold.

At the top are the two docs that were the day one films last year. If I was the producer of Twenty Feet From Stardom, this fact would make me pretty damn happy. Last year’s Searching for Sugar Man and Queen of Versailles both sold for mid six figures and enjoyed enormous success.Twenty Feet sold on Thursday to Radius and the Weinstein Co. in one of the first deals at the festival. It is scheduled to launch theatrically in the States later this year.

Performing well beyond expectations is Searching for Sugar Man which won the world documentary audience award has grossed just over $3,000,000 in the careful hands of SPC. Acquired for mid six figures the film is easily profitable for the distributor and with distribution in at least 11 other countries and an international gross of over $2,000,000 it is also easily profitable for the filmmakers.

As with a number of films we will get to in a bit, this film had a rather slow rollout and opened to a decent, but not spectacular PSA of $9,153 on 3 screens. As with other top grossing docs from prior year’s this film deals with a would-be star, a Cinderella story, and has a bit of a mystery. For 18 weekends in a row, the film averaged over $1,000 PSA which is nothing short of remarkable. At its widest, it played in 157 screens, but at that point it had already grossed well over a million.

While Queen of Versailles opened to a much higher PSA of $17,109 on 3 screens it also expanded much more quickly and the gross suffered slightly for it. Its widest release was on 89 screens and that happened in its 4th week of release. It had 10 weekends averaging over $1k for the PSA, but basically dropped its count from week 4 on. That said, the run is nothing to complain about and a film of this type was never going to be able to play to the slow burn that Searching For Sugar Man has. What is worth noting, Magnolia chose not to day and date VOD and paid mid six figures for the film. With a total gross of $2,401,999, this film is also quite profitable for the distributor and has been a great performer on iTunes and other digital platforms since its theatrical ended. Internationally it has only been released in the UK where it has grossed $93,707.

The only company to have two documentaries from this year’s fest that grossed over $250k is Indomina. The Imposter and Something From Nothing: The Art of Rap. The latter was a combined deal with BET handling the TV premiere. The total acquisition cost was over $1,000,000.

Two other films that performed surprisingly well are the self-released Detropia and the Oscilloscope acquired concert doc Shut Up and Play the Hits. Detropia left Sundance with offers, but none of which felt right for the ode to those who have stayed in my hometown of Detroit. The filmmakers who are something close to Documentary royalty rose over $60k on Kickstarter. They opened on one screen in Royal Oak (a Detroit Suburb) and grossed $21k for the weekend. While the film has played all right outside of the Midwest, with over 1 month in the big Apple, the bulk of its grosses came from theaters throughout Michigan and the rust belt area. They were able to book both solid art house venues as well as major chains that typically would never screen a documentary. To date, the film has grossed over $377k and is a great model for DIY Theatrical. And while Burn premiered at Tribeca, the doc also did quite well relying on a regional approach. The film about Detroit firefighters has grossed just over $100k with the bulk of it coming from a theater in Chicago and a theater in Metro-Detroit. It too is a DIY, but expanded to far fewer markets.

Shut Up and Play the Hits is a band’s farewell concert doc and so Oscilloscope’s decision to do a special one night engagement at theaters around the country made perfect sense. On 161 screens it grossed $378,751! That total is from one night! It then announced that due to strong demand it would play longer. Though it disappeared from theaters in under a month it managed $510,334 and with fans doing the advertising for Oscilloscope this film is easily profitable.

The Other Dream Team was distributed by the fledgling Film Arcade in partnership with Lionsgate. The film grossed $135,228 during its 7 week run (comparatively short to a number of other films on this list). At its peak, it played in 14 theaters. While not a slam-dunk and most likely at a financial loss to the distributor, this at least shows their potential for future releases.

The Political Issue Docs

The House I Live In sold digital rights to Snag Films, but had a theatrical courtesy of Abramorama and has grossed $186,059 in the US. It opened on two screens to a PSA of $12,122 and has never played in more than 12 theaters. With Snag bound to maximize digital, this is a decent performance that only seems weaker with the high profile names that have gotten on board this film and for winning the Sundance jury prize.

How to Survive a Plague is a major theatrical under performer for Sundance Selects. They paid high six figures for this emotional macro look at Act Up. With the film currently grossing $132,055 theatrically and most likely out of theaters for good save for a decision to bring it back in thanks to its Oscar nomination. Is grosses are not terrible, but far from great. Despite near universal critical praise, it had a number of barriers that it was unable to get over. Gay audiences are not as theatrically loyal as they used to be. They have shown that AIDS is not something they want to relive in the theaters. And straight audiences usually avoid films anchored by gay content. It will inevitably make the bulk of its money on VOD, but considering its potential, this is nothing short of a disaster. Performing much better for the distributor was Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry which at $489,074 just narrowly missed the ½ million mark. The acquisition price was not stated so we can assume it was below mid-six figures and most likely a decently profitable film for Sundance Selects.

5 Broken Cameras has grossed $75,607 in the hands of Kino Lorber and played in theaters for 22 weeks. It never played wider than 6 screens and 15 of the weeks it was in theaters it only played on 1. With next to no advertising costs and an Oscar nomination to boot, this foreign film should recoup for the budget minded specialty distributor. What remains to be seen is if any new theaters will book the film leading up to the Oscars.

The Invisible War (disclaimer:TFC is the sales agent) is a different kind of success. While the film is the lowest grossing US Documentary film to get a theatrical out of Sundance 2012, it did something none of the other films were able to; the release resulted in changes in governmental policy. There were multiple screenings held at the Pentagon and the film had a fantastic festival run to boot. Just as with the also Oscar nominated micro-budget Gasland, the success shouldn’t be judged simply by the audience, but the changes being implemented to military policy. It is also one of the highest grossing films for Cinedigm and has dwarfed the performance of its other festival acquisitions this year. Box office gross $64,010.

Escape Fire on paper would seem to have a lot going for it. The film is about a major crisis that factored into a Presidential Election year. It was distributed by Roadside Attractions who maximized more challenging films like The Cove and Project Nim to mid-high six figure grosses. They also partnered with TUGG to spread the word. However, the film had a number of things working against it; some of which could have been fixed. Their social media campaign was something of a hot mess. Less than a month before announcing their deal with Roadside, the production attempted a second Kickstarter campaign to raise funds for the theatrical, yet they simply stopped. That suggests to me that most likely the deal with Roadside was a service deal. Tugg did add some interest in a few cities, but it opened on 26 screens and was down to 2 the following week. At present, it has just barely out grossed Marina Abramovic, but that film played on fewer screens and most of its run took place after it had premiered on HBO. More importantly, Escape Fire has failed to spark legislative change. Box office gross $87,577.

Also underperforming is West of Memphis produced by Peter Jackson. The film came out the end of December and still has 90 or so theaters yet to open in, but its initial response has been tepid at best. With SPC guaranteeing the maximum payoff possible, this film may ultimately be able to gross about $200,000, but even that mark might not be reached. To date, it has grossed only $57,416 on 9 screens. While the acquisition price is not known, just by virtue of advertising costs alone, this film will not be profitable for the distributor. It will also lose out from not making the Oscar shortlist and having a run time of well over 2 hours.

Marina Abramovic: The Artist is Present was released in theaters by Music Box Films who chose to release the film in just 2 theaters before it premiered on HBO to a gross of over $45k. It ended its run with $86,637 and most of its additional theaters were special engagements at museums and other non-traditional theater venues. This reduced costs for extra markets and as a result of creative thinking, this film is the highest grossing doc to have premiered on HBO this year and outgrossed all the other ones combined.

Barely registering were a number of world documentary films and Doc Premiere films, in the case of the latter it is perhaps a bit surprising when factoring in the range of successes among the general premiere films (which will be addressed in my next post).

World Doc Jury winner The Law In These Parts grossed $11,227 on one screen for one month thanks to Cinema Guild. Putin’s Kiss which premiered at IDFA was even lower at $9,114 on one screen for about 3 months. Grossing just barely more than both of them are Zeitgeist’s China Heavyweight ($10,550 on 4 screens for 3 months) and Payback ($17,979 on 3 screens for 4 months). The total gross of those two films is less than the box office gross of SXSW acquisition Gregory Crewdson which is still in theaters and clocking in at $42,822. The Ambassador managed $28,102 for Drafthouse which considering they have their own theaters to help release the film, makes it possible that the theatrical wasn’t a total financial loss.

Bones Brigade had a DIY theatrical courtesy of The Film Sales Company and did not report grosses, however a complete case study of what they accomplished is now available on the Topspin Media blog. The film is now available on digital platforms. Big Boys Gone Bananas had an Oscar Qualifying run and Indie Game: The Movie did not report grosses but as was covered in an earlier blog post recouped using a number of other creative DIY methods. They also wrote their own case study and published it on their blog.

Love Free or Die has a DVD/VOD deal with Wolfe, The D Word, About Face, Me @ The Zoo, and Ethel are all HBO Docs. Ethel had an Oscar qualifying theatrical and made the shortlist, but did not get nominated. After successfully raising $29741 on Kickstarter for finishing funds, Me @ the Zoo was acquired for $500,000 and the filmmakers recouped.

Be sure to check in next week for my final post on Sundance 2012 films with a look at the narrative films released over the last year.

Bryan Glick January 23rd, 2013

Posted In: Distribution, Film Festivals

Tags: documentary, documentary film distribution, film distribution, independent film, Sundance Film Festival

Evaluating the New Independent Film Distributors in 2012

Every year there are new companies formed that want to make a big impression in the distribution world. The 2012 crop of new indie distributors is unique in that a lot of them aren’t really new. They include sales companies expanding their reach, Digital companies going theatrical and international companies making a domestic presence with varying levels of success. This post will take a look at how independent film distributors fared over the last year.

Indomina Releasing came out big at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival acquiring four films. They are the only company to have two documentaries from this past year’s fest gross over $250k (The Imposter and Something From Nothing: The Art of Rap). Something from Nothing was a combined deal with BET handling the TV premiere. The total acquisition cost was over $1,000,000, and though it is unknown how the cost was split, it is reasonable to assume that the TV deal was at least half of the paid price. They launched Something from Nothing on 157 screens in the opening weekend and the film grossed $288k. While it is far from their most successful film, by opening as wide as they did and having a partnership with BET, they reduced their liability and at worst it was a modest loss and most likely profitable after digital platforms.

The Imposter only opened on one screen which is where it stayed for its first two weeks racking up almost $50k! It then expanded ever so slowly to 2 then 8 then 13 screens at which point it was in its fifth week of release and had grossed over $150k. From week 5-6 its PSA (per screen average) went up by over 25% and it broke the 250k threshold while playing on 19 screens. At its peak, it played on only 31 screens and was still averaging over $3k PSA. The film, which opened in July, played until early December! When it comes to documentaries with harder to define subjects, it is almost always better to let word of mouth build. With few exceptions, only high profile names should be opened on a larger screen count. With a total North American take of $898,317, this film should be quite profitable for Indomina. The acquisition price is not known, but based on reporting practices, we can assume it was no more than low six figures. It has grossed another almost $2,000,000 worldwide. Finally they released Holy Motors which has soared to the $588k mark in 29 theaters in the US despite being nearly impossible to describe. Not shying away from edgy genre fare or challenging documentaries, the sky is really the limit for this relatively recent entry into the theatrical game.

Also performing quite well is Submarine Deluxe which is a branch of the Braun’s Submarine Entertainment. Following the success of PDA, Submarine has stepped in when top documentaries either didn’t attract the offers they thought they deserved or when things went south with the distributor They recently released Chasing Ice which has grossed over $940k with the $1,000,000 prize in sight. It made the Oscar shortlist for best documentary and though it didn’t make the final cut, it did get an Oscar nomination for best song. It has also targeted some rather untraditional theater choices and markets ranging from Cinemark theaters to one screen arthouses in small towns. They did this with the help of Emerging Pictures. Emerging Pictures has helped with the releases of the four highest grossing docs from Sundance 2012 (Doc distributors take note!) The PSA each week has held relative steady since their major expansion though it did finally see its PSA drop below $1k. It ultimately played on 53 screens. As with some films mentioned above, it has a television deal with National Geographic so this is all just icing on the cake. What remains to be seen though is if Submarine Deluxe will step in for a film that is not also a sales client?

Though not quite equaling the success of the above two companies, there are a lot of positives to be said for The Film Arcade. They released two films in 2012 each grossing around $150k. The Other Dream Team and Simon and the Oaks used very similar release strategies. They opened on just 1 or 2 screens then expanded to 7 and then to about a dozen with PSA’s holding relatively steady for a few weeks after the initial second week drop. The problem is, neither film had long theatrical runs where they were able to maximize locations. They have established a solid partnership with Lionsgate that will help the films on other mediums and both films were truly difficult to sell foreign films. The question is, can they produce a true breakout?

Adopt Films finally at year’s end has shown some potential. They have a good eye for quality foreign films, but have failed in converting that into box office success. They literally bought every award winning film out of Berlin 2012 and despite fantastic reviews for Sister and Tabu, they were unable to convert it into audiences. Sister has grossed less than $25k, Tabu opened on one screen with a PSA of about $5k and a new film, Barbara, was released timed for the Oscar shortlist, but it failed to make the cut. Its opening weekend grosses were passable, but based on the awards campaigning costs and the amount of screens they opened on, it is an immense underperformer compared to other awards fare. That said, in one week Barbara has out-grossed all of Adopt’s films combined. Through its 2nd week it had passed the $200k mark. Adopt has chosen not to report grosses online.

Entertainment One is not a new company at all, but is new to the American marketplace as a distributor. They have long been dominant in Canada and after acquiring Alliance, they are clearly the highest profile Canadian indie distributor. In the US, they have released a number of films that have featured big name stars, but mediocre reviews. While they took in $763,556 from Cosmopolis that is far from a great gross for a film from an established director. They opened on three screens and averaged $23,466 which is solid, but when they expanded the following week to 64 screens, their PSA dropped by almost 90% to $2,453. It only averaged a PSA over $1k for four weekends and then quickly faded out. That is much better than Dustin Lance Black’s directorial debut Virginia which ended its run at $12,728. The also star studded Jesus Henry Christ did slightly better on a lower max screen count of 3, but still only pulled in $20,183 by the end of its run. The 2012 Sundance acquisition Wish You Were Here has yet to be released and it too received less than stellar reviews. That said, even when they have a well-reviewed film, they haven’t always converted it to a success. Carol Channing: Larger than Life was anything but with $22,740. All the more disappointing by the fact that human interest docs are doing quite well as a whole.

They also have A Late Quartet which has quietly grossed over $1.4 mil to date. It has had a PSA over $1k for 9 weeks and will most likely double the gross of Cosmopolis. For a film that stars Christopher Walken, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Catherine Keener, and Imogen Poots this still feels kind of like a flop.

Performing below expectations is TWC-Radius. While this ultra-VOD off-shoot of The Weinstein Company paid $2,000,000 each for Lay the Favorite and Bachelorette, the films combined for a theatrical take of less than $550,000. Bachelorette did debut at #1 on iTunes, but with having to pay the premium price for 60 theaters to book the film and the outsized advertising expense to launch the film and by default the TWC-Radius label, it is at best barely profitable. Despite opening in 61 theaters, Lay the Favorite has grossed less than $25k. Or in simpler terms, the film was seen by more people at Sundance than it was in its entire 61 screen theatrical run. The rest of the titles on the Radius label are basically the leftovers of TWC mistakes including The Details and Butter. None of these have averaged over $1k PSA in their opening weekends.

Looking ahead to 2013, Picturehouse is back and we will see if they strike for anything at this year’s Sundance festival. I also expect Indomina Releasing and Entertainment One to flex some muscle.

Next week, I will look at how the Sundance 2012 documentaries fared in release. Stay tuned!

Bryan Glick January 17th, 2013

Posted In: Distribution, Distributor ReportCard

Tags: Adopt Films, BET, Entertainment One, Film Arcade, independent film, independent film distribution, Indomina, Lionsgate, Submarine Deluxe, TWC Radius

The Independent’s Guide to Film Exhibition and Delivery 2013

2012 was a profound and often painful year in terms of the rapid technological change impacting the delivery and exhibition of independent film.

2012 was the year we wrapped our heads around the idea that there are virtually no more 35mm projectors in theatrical multiplexes, and that the Digital Cinema Package (DCP) has taken its throne as king – right alongside its wicked little stepchild, the BluRay.

2012 was the year it became clear that the delivery and exhibition formats we’ve been relying on for the last few years (especially HDCAMs) are no longer sufficient, and that in order to keep pace with the marketplace, we must now embrace the next round of digital evolution.

There are many filmmakers who will now want to stop reading, thinking “ughh, techie-nerd speak, that’s for my editor and post-supervisor to worry about.” You may believe you are first and foremost an artist and a storyteller, but in today’s world your paintbrushes are digital capturing devices, and your canvas is the wide array of digital delivery systems available to you. To shield yourself from the reality of how technological change will affect your final product is to face sobering and expensive complications later that will dramatically impact your ability to exhibit your film in today’s venues (including film festivals, theatres, and other public screening venues), as well as meet the needs of distributors and platforms worldwide.

And, so, for this New Year, I offer this “Guide to Exhibition & Delivery 2013,” a quasi-techie survival guide to the landscape of technological change in the foreseeable future, keeping in mind that this may all look very different again when we revisit this just a year from now…

What changed in 2012?

As 2012 began, major film festivals worldwide had largely coalesced around the HDCAM (despite slight but annoying differences in North American and European frame rates); and distributors and direct-to-consumer platforms were largely satisfied with HDCAM or Quicktime file-format deliveries, although varying platforms required different file specifications which could prove difficult for independent filmmakers to match (most notably iTunes). In addition, a large sector of the distribution landscape, including small film festivals, educational institutions (universities, museums, etc), and even small art house theaters remained content to screen on DVD and other standard-definition formats. The high-definition BluRay – with its beautiful image quality and powerful economic edge in terms of cost of production, shipping, and deck rental — was also emerging as an alternative to HDCAM, Digibeta, and DVD exhibition, despite the warnings by the techie/quality-control class that BluRays would be perilously unreliable in a live exhibition context.

But behind the scenes, the engine of the corporate machine driving studio film distribution was already fast at work driving top-down change. Finally, after years of financial impasse as to how to equip the theatrical network with digital projectors, the multinational Sony / Technicolor / Christie Digital / Cinedigms of the world had immersed themselves fully in the space and converted the North American multiplex system to a digital, file-based projection standard set by DCI LLC (a consortium of the major studios) – saving the studios immeasurably in print and shipping costs, as well as standardizing and upgrading image quality and providing additional security against piracy. This standardization as defined by the DCI studio consortium had already been growing in Europe for years before the North American market caught up, and became known worldwide as the DCP (Digital Cinema Package).

Once the largest technological and exhibition purveyors worldwide had made their move towards standardizing film exhibition, the writing was already on the wall, although it would take several more months to make its impact fully felt in the independent world.

What is a DCP?

A Digital Cinema Package (DCP) is a collection of digital files used to store and convey digital cinema audio, image, and data streams. General practice adopts a file structure that is organized into a number of Material eXchange Format (MXF) files, which are separately used to store audio and video streams, and auxiliary index files in XML format. The MXF files contain streams that are compressed, encoded, and (usually) encrypted, in order to reduce the huge amount of required storage and to protect from unauthorized use (if desired). The image part is JPEG 2000 compressed, whereas the audio part is linear PCM. The (optional) adopted encryption standard is AES 128 bit in CBC mode.

The most common DCP delivery method uses a specialty hard disk (most commonly the CRU DX115) designed specifically for digital cinema servers to ingest the files. These hard drives were originally designed for military use but have since been adopted by digital cinema for their hard wearing and reliable characteristics. The hard drives are usually formatted in the Linux EXT2 or EXT3 format as D-Cinema servers are typically Linux based and are required to have read support for these file systems.

Hard drive units are normally hired from a digital cinema encoding company, sometimes (in the case of studios pictures) in quantities of thousands. The drives are delivered via express courier to the exhibition site. Other, less common, methods adopt a full digital delivery, using either dedicated satellite links or high speed Internet connections.

In order to protect against the piracy fears that often surround digital distribution, DCP typically apply AES encryption to all MXF files. The encryption keys are generated and transmitted via a KDM (Key Delivery Message) to the projection site. KDMs are XML files containing encryption keys that can be used only by the destination device. A KDM is associated to each playlist and defines the start and stop times of validity for the projection of that particular feature.

As a result of all the standardized formatting and encryption features, the DCP offers a quality product generally considered to be superior to 35mm (while simultaneously conforming to the beloved 24 fps rate of 35mm), and a product that can theoretically be shared around the world with less variables and greater reliability than most formats (since 35mm) to date. Given the confusing array of formats facing filmmakers in recent years, there are many ways that the DCP revolution seems a singular advancement worth applauding, and at least on the surface, as a clear way forward for film exhibition and delivery for years to come.

So what’s wrong with that?… DCP survival for independents.

Before running out to master your film on DCP now, it is important to consider at least the following mitigating factors, 1) the utility of the format, 2) the price of DCP (including the hidden costs), and 3) the newness of the format and the inherent dangers associated with new formats, and 4) the ways that DCP will not save you from the usual headaches of delivery, and is in many ways an existential threat to independent film distribution as we currently know it.

With regards to the utility of DCP, remember that it is currently a cinema exhibition product, not a format that will be useful for delivery to distributors, consumer-facing platforms, DVD replicators etc. So, obviously you must be quite sure that you have actually made a theatrical film, and by this I mean theatrical in the broadest sense possible…i.e. will your film actually find life in cinematic venues including top film festivals etc. Following the industry at large, film festivals around the globe are in hyper-drive to convert to DCP as their preferred or even exclusive format. Going into the film festival circuit in 2013 and forward in any mainstream/meaningful way without a DCP…especially for narrative features….will be challenging to say the least (although likely still doable if you are willing to forfeit some bookings and some quality controls). But if you aren’t sure yet if your film will actually command significant public exhibition at major festivals and theatrical venues, you probably shouldn’t dive into the pool just yet.

Not surprisingly, the largest concern to independents is the issue of price. While nowhere near to the old cost of 35mm, DCP does represent a significant increase in mastering cost over HDCAM, Digibeta etc. In researching this article, most labs quoted me a rate of approx. $2,000 for a ninety minute feature, plus additional costs for the specialty hard drives and cables etc. that put the total closer to $2,500 +. As is the case with most digital products, however, it appears the costs are already headed downward as more and more independent labs get into the space, and it seems reasonable to assume that the price-conscious shopper should be able to find $1,500 and even $1,000 DCPs in the near future (especially with in-house lab deals working for specific distribution companies).

Following the initial mastering costs, the files can be replicated onto additional custom hard drives for prices in the range of $300 – $400, which is at least relatively commensurate with HDCAM replication. This replication process is controversial however — there is no doubt that one can decide to skirt this cost by transferring the files to standard over-the-counter hard drives that run in the range of $100 (we have already distributed one film theatrically and successfully using standard, low-price hard drives). But many labs and exhibitors will warn you against this, telling you that using non-custom hard drives and cables increase the chance that the server at the venue will not be able read the files, and therefore unable to ingest and project the film when it counts most.

In fact, to avoid these potential compatibility issues with differing hard drives, cables etc, some exhibitors (most notably Landmark) are requiring distributors and filmmakers to use specific labs who encode all their content, which perilously puts the modes of production in the hands of the few, and may ultimately keep the cost artificially high. And while indeed there are many reasons to fear compatibility issues between DCP and server (I have already heard of/attended numerous screenings cancelled or delayed in 2012 due to DCP compatibility issues), it is in fact this level of lab and exhibitor control over the product that makes me very nervous about the future of DCP in the independent distribution space.

The most dramatic example of the DCP “threat” to indie distribution is the emergence of the onerous VPF (Virtual Projection Fee) that is now being applied at many (if not most) mainstream theatrical venues (including art house chains like Landmark). The VPF is an $800 – $1,000 per screen fee that is added to the distributor or DIY filmmaker’s distribution costs, either leveraged against the film rental or added as a an additional cost to the four-wall. This fee may go down after 20 or so screens, or in a films 3rd or 4th week of adding cities, but otherwise it is largely a fixed fee tacked against the already low profits of most independent theatricals today.

The reason for the fee stems from the fact that the projection companies mentioned earlier (Sony, Christie Digital, etc.) in fact financed the introduction of the digital projectors into the theaters, so the VPF fees largely go towards the recoupment of their investments. But, even once these initial investments have been paid off, it is likely that the VPF will continue as a valuable money-maker for the tech companies, and is not likely to disappear any time soon. And in this age where the financial model of independent theatrical distribution hangs so perilously on a knife’s edge anyway, the VPF almost feels like a coup-de-grace dooming small theatrical releases from the get-go.

Another troublesome aspect of DCP distribution is the very encryption technology that was meant to make the product safer from piracy, but also adds an additional level of bureaucracy and cost that most independents cannot realistically afford. The encryption keys (known as KDMs) are controlled entirely by large labs like Technicolor, and are transferred directly from companies like Technicolor to specific theaters within specific venues for limited windows of time. Anyone who has been involved with the free-wheeling nature of independent distribution knows that relying on large labs for print trafficking and shepherding is expensive and time-consuming, and cuts deeply into already marginal profits. And if you are creating DCPs for film festival distribution, the very idea that a single theater in a far-flung locale must rely on a 3rd party lab to get a specific KDM code for its screenings seems akin to courting disaster to me. Indeed, I know several independent festivals that are not accepting DCPs at this point, simply because they refuse to subject themselves to the whims of the studio KDMs.

For the above reasons and more, I’ve encountered several Industry folks who have been so blunt as to tell me, “DCPs were invented to put independents out of business.”

While I’m not quite ready to go there, I will add that the most pernicious aspect of DCP introduction into the market in my opinion is the way that they are already creating a new two-tier distribution market between those larger festivals and venues that can afford DCP projection and those mid-sized and smaller than cannot and perhaps never will be (given the prohibitive cost of the projector technology). As such, DCP does not replace the HDCAMs, Digibetas etc of old, it is rather an additional format that independents must contend with – good in some situations, useless in others – and yet an additional cost to add to your contemporary distribution budget.

As a result of the emerging two-tiered system; with DCP for the better-funded venues and alternatives for the smaller, less-funded; there remains a gaping hole in the contemporary exhibition system which is increasingly filled by the most seductive and problematic format available to independent filmmakers today – and by that of course I mean the BluRay.

The bastard step-child, the BluRay.

Yes I used the word bastard deliberately and with purpose, because the BluRay is the most enticing and simultaneously cruel of the contemporary exhibition/delivery formats.

For independent filmmakers and exhibitors (including theaters, festivals, and other venues) alike, the BluRay seems at first glance an ideal option – inexpensive to produce and inexpensive to ship – to go along with inexpensive players and projectors that can be bought at consumer-level prices. And the quality of both image and sound is usually shockingly good – usually commensurate with the best HDCAM ever had to offer.

As such, the economics of film exhibition have lead to an explosion of BluRay use in 2012, with the format beginning the year as an enticing alternative but quickly emerging as the mainstay of mid-to small size venues in both North America and Europe. But just as quickly as BluRay has emerged, a truism about today’s BluRay technology has become painfully clear – it exists at consumer-level pricing because it is not a professional product – and its failure rate in live exhibition context is dangerously (if not outright unacceptably) high.

Consider the following: In recent years prior to 2012, it was nearly unheard of that a booking at a theater or festival should need to be cancelled or delayed due to exhibition format failure…because formats like 35mm or BetaSP or Digibeta or HDCAM were nothing if not reliable. But suddenly in 2012, the cancelled screening, or the delay mid-screening, or the skipping and freezing of a disc mid-screening became commonplace. To our dismay, it has become normal in 2012 to stop a screening mid-stream for a few moments to switch to a back-up DVD to replace a faulty BluRay. In our haste to transform to the miracles that BluRays seemed to afford us, a variable of chaos and unreliability has been introduced…and as yet there are no easy answers to this conundrum anywhere in sight.

There are numerous factors that account for BluRay unreliability – too many in fact to list in their entirety in this posting. There are many compression issues – resulting in variable gigbyte-per-layer Blurays from 25GB per layer to dual layer to triple layer to quadruple layer discs etc. These are profoundly complicated by player-compatibilty issues – meaning that many BluRays that play perfectly in one player will not even load in another. There are also significant regional differences between BluRay formats – similar but even more complicated than the old PAL vs. NTSC coding schemes. Layer onto this the fact that BluRays are fragile and scratch easily and do not traffic well and are easily lost, and we have arrived upon a formula for delivery chaos, to say the least.

As of today, as we go to print on this post, an uneasy truce on the proper protocol of BluRay delivery seems to be emerging Industry wide…for the moment at least. If you are going to screen your film on BluRay, you must provide at least a DVD back-up in case something goes wrong. Ideally, you should provide 2 BluRays, each of which have been tested, and a DVD back up as well. You still might experience screenings where your film will be stopped mid-stream, and replaced by one of the back-ups, but at least you won’t likely face the humiliation of a fully cancelled screening.

It’s hard to call this progress….but for the moment this is the price we are paying for digital evolution. The irony is…if BluRays were just a little cheaper than they currently are (generally somewhere between $10 – $40 each following an initial $300 – $500 investment), we might all dispense with attempting to traffic them completely, and just provide pristine BluRays for each screening (with somewhat less propensity for failure). This might solve some of the trafficking and delicacy issues, but this does not seem realistic for most filmmakers just yet, especially as so many other factors still come to bear. To be clear, the issues of BluRay unreliability are far more complex than just scratches and trafficking issues, so providing pristine BluRays to each booking will not solve all the issues, and DVD backup will still be necessary for the foreseeable future.

The further irony here is that DVDs, long since seen as less reliable although in all other ways preferable over the old VHS format, have now become the stalwart back-up to the BluRay…for even the traditional 5% failure rate for the DVDR format have become models of reliability as compared with the mercurial nature of the contemporary BluRay. Thankfully, today’s DVDs rarely fail in a pinch…

Where do we go from here?

When finishing a film in early 2013, filmmakers are now faced with the question of what delivery formats to create to meet delivery and exhibition demands. However, given the volatility of the current delivery landscape, it may be actually best to NOT commit to any particular exhibition format, and instead finish your film in a digital (hard-drive) format that you can keep as a master at a trusted lab for future needs down the road. It is advisable to have your film in the most flexible format possible, until you are forced by circumstance to deliver a specific format for a specific purpose.

The most flexible and useful format to initiate most exhibition/delivery formats at the moment is the Apple ProRes 422 digital file. Apple ProRes is a line of intermediate codecs, which means they are intended for use during video editing, and not for practical end-user viewing. The benefit of an intermediate codec is that it retains higher quality than end-user codecs while still requiring much less expensive disk systems compared to uncompressed video. It is comparable to Avid’s DNxHD codec or CineForm who offer similar bitrates which are also intended to be used as intermediate codecs. ProRes 422 is a DCT based intra-frame-only codec and is therefore simpler to decode than distribution-oriented formats like H.264.

From your ProRes 422 file, you will be able to make any format you need for today’s distribution landscape….from DCPs and BluRays to HDCAMs and any digital files you may need for platform distribution worldwide. This makes it ideal as an intermediary format as you consider your next steps forward.

In 2013, the needs of your exhibition formats and delivery formats will likely be determined by how successful your film turns out to be. If your film turns out to be truly theatrical, you will likely need a combination of DCPs and HDCAMs and BluRays to meet the demands. But if your film turns out to have limited public exhibition applications, then perhaps a mix of BluRays, DVDs, and digital files may be all you need. Rather than make those decisions in advance, we recommend you pursue a delivery strategy that lets the marketplace make those decisions for you.

In 2013, these delivery strategies will be impacted by the rate of technological development, just as they were in 2012. For the time being, it seems to wisest to counsel that we not get ahead of ourselves, and deliver films as a ProRes 422 file available for quick turnaround at a trusted lab with multi-format output capacity. From there, we can be assured of the ability to take our opportunities whenever and wherever they may lead us.

Jeffrey Winter January 7th, 2013

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Theatrical

Tags: BluRay, DCP, Digibeta, Digital Cinema Package, digital delivery systems for film, digital film distribution, file formats for film, HDCam, independent cinema, independent film, independent film distribution, Jeffrey Winter, KDM, theatrical distribution

Rethinking Your Key Art Game Plan, Part 2

Guest blogger is The Film Collaborative’s Creative Director, David Averbach, who has worked with dozens of TFC Clients and other filmmakers to help them create and refine their key art. See Part I HERE

Note: This Key Art series is intended for micro-budget filmmakers whose crew is not under a union contract. If your film’s crew is under an IATSE contract, you will need to abide by the rules regarding still photographers on set as forth by the union. We have been advised that there may be penalties involved by bringing an intern or PA in to shoot stills.

Last week, in Part 1 of this blog series, I discussed how relying solely on 1920×1080 pixel frame grabs was a bad idea if one wanted to create a poster that featured some sort of main image. In an ideal world, your entire film would be shot on a 5K camera, and you could pull as many frames from the footage as you wanted. That would be Plan A. But in the real world, many filmmakers emerge from their shoots with only 1080p frame grabs, and that’s not going to work.

Another problem is about marketing. During the chaos of a film shoot, filmmakers often forget to think about the art they might need to support a variety of possible marketing ideas and concepts, and are therefore left with fewer choices and placed in an ultimately weaker position vis à vis possible options on how to market their film without an expensive and inconvenient reshoot.

This blog series offers some concrete advice on how you can protect your film’s marketing future by adding a few inexpensive steps to your key art game plan.

A photographer on the set with a second 5K camera is great if you can afford it. That would be Plan B. But if your budget is limited (or even if it isn’t), last week I suggested a third plan—a “Plan C”—that as far as I’m concerned should be executed whether your film is entirely being shot on a 5K camera or whether there is a professional photographer on set or not. I’m sure I made some of you cringe by suggesting that you pick up a cheap but powerful point-and-shoot camera and putting an intern or production assistant in charge of shooting “hi-res scraps”—basically a lot of shots of the characters in various poses during the down time on a film shoot—that can be utilized down the line by a designer to execute the envisioned poster. The bottom line is this: as a designer myself, I’d rather have the opportunity to work with shots taken from a cheap but decent camera than nothing at all.

One of the reasons I suggested this is that while professional photographers undoubtedly bring a great deal of talent to a set, their exact skill set may not be entirely conducive to producing key art elements. A photographer’s eye for composition usually relies on what they see in bounds of their view-finder, and having them do some of the things that I’m going suggest here in Part 2 of this key art blog series may cause a bit of pushback and confusion. It’s best to let them do what they usually do and concurrently (i.e. Plan C) have a go with the point-and-shoot/intern thing. Of course you don’t have to use a point-and-shoot camera if you have a better one available. But I work with a lot of filmmakers whom I feel would find an excuse not to do this if there were more work/more cost involved. And if you use an intern or a production assistant, or perhaps a rotate through a handful of them, you’re giving them something real to do, which will inspire them to do a better job in everything they are their to do for you. It’s a win-win. Have them take as many photos as they can. Just make sure you buy some extra high capacity compact flash cards.

Now onto Part 2…

You may have an idea of what you want your poster to look like even before you begin your film shoot. Great. But don’t plan for that to be the only idea you execute. You should produce the photos necessary to execute MANY ideas. Here are some possible concepts.

Have a discussion about marketing before your shoot and come up with two dozen ideas. They don’t have to be all that specific. If your film involves one main character, or a pair of characters, then let’s assume for the moment that you could feature them in some way in terms of poster real estate…Accordingly, my first example will be to think a bit about how you could execute a concept that features a single image that takes up the entire poster. Again, you decide what that single image should be…perhaps it’s your main character. Perhaps it’s two characters. Perhaps it’s something else. But here’s the takeaway: at this stage, don’t produce a shot. Produce ELEMENTS.

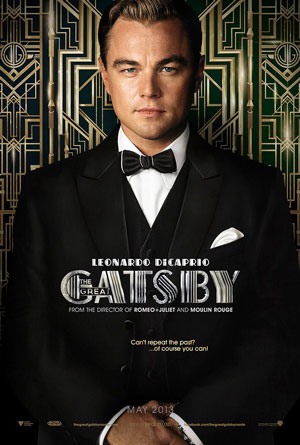

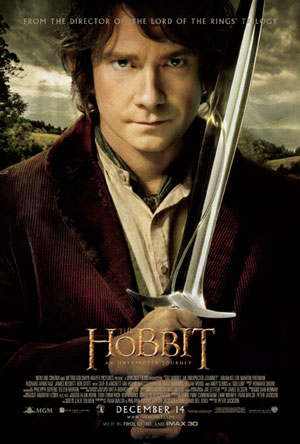

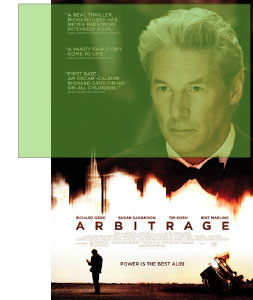

Let’s have a look at a few posters from current movies that involve a single shot. If these movies aren’t your taste, it doesn’t really matter…the concepts can be applied to almost anything or any style of poster.

|

|

|

Looking at these posters closely in as full a resolution as I could find online, they have one thing in common: each image of the actor is a cutout placed in front of a different background from which the shot was taken. Artbitrage is the most blown-up…if you walk up to this poster in a theater and had a close look, I suspect, you’d see quite a bit of distortion. In The Hobbit, they’ve added a bit of noise to mask the upresing and blend it in with the colors of the bucolic background scene, but I suspect the picture was a much higher res to begin with. Gatsby remains the clearest photo, and the crispness works well with the art deco concept. A designer could create any of these looks with a photo of like the one of Leo DiCaprio, but it would be hard to create a Gatsby-like effect with the photo of Richard Gere.

In the absence of a large format camera in a studio environment, to get as full a resolution as possible, here’s what I suggest, and I know this is a bit unorthodox, but it’s pretty straightforward. Set up a white sheet as a background, or if your subject has a lot of fly-away hair, you may want to try it with a green or blue screen. (I found a cheap one here.) This will allow the designer to take away the background to produce a cutout. This is really no big deal for a graphic designer, unless there is a ton of hair involved, in which case, be sure to try it with a number of different backgrounds. This isn’t a shampoo ad, so shaving off a little hair is forgivable in this arena.

First, take a normal full body shot in portrait orientation just so there is at least one shot of the entire scene you are trying to capture.

But this shot will not be the one that is used. Instead, break the photo up into several shots…the trick is not to hold the camera in portrait orientation but keep it in landscape while you do this…then later on your designer reassemble them into a unified whole.

Why do it this way? Last week, I showed you what you can expect to achieve with a 16.1 megapixel camera:

![]()

Doing it this way will give you the most resolution to work with…

You may need to do it a few times to insure consistency in terms of lighting etc., but with the magic of photoshop, this shouldn’t be much of an issue. You’d want to be careful not to break the shot in the middle of any complicated parts, such as the person’s eyes or mouth, for example.

Start with the person’s face…make sure not to cut off the top of the head (even though two of heads in the posters here are cropped)…

|

|

|

Then quickly lower the camera vertically and take another shot, so that the second overlaps just a bit, to get the upper part of the torso.

|

|

|

Make sure to take dozens of shots like these, so that you have enough photographs to mix and match, as sometimes the pictures can vary in terms of lighting, or your hand is not in the exact position, etc. If there is a prop involved, I would not have that in the shot, but just have them grip something similar and photoshop the item (like a sword) back in later. (Remember to also take pictures of the prop using this technique.)

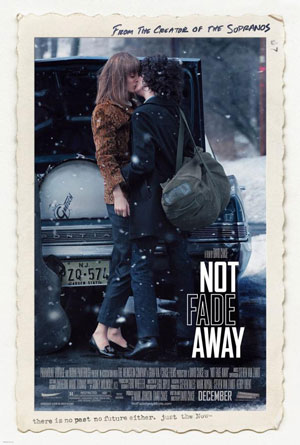

Perhaps you don’t want to feature just one character…after all, your film may not involve such a recognizable star as Richard or Leonardo. Let’s say you really want a particular shot of two of your main characters in some sort of pose. Like in the following film, Not Fade Away.

|

|

|

|

It is a bit counter-intuiative, but what I would do here is photograph the two characters in front of a solid background, not in front of the car. Then take a background photo (using the same technique here) of the car without the people. Then have your designer photoshop them together later. I would even go a step further and take a picture of the car without its background, and then take the trees as a separate photo. You never know how the composition will work best with your title treatment, or in different orientations (have a look at key art that is modified for a landscape orientation in iTunes trailer art…you’ll want to be able to move things around to create the look you want in the space that is allotted).

The point is that you are producing elements, not photos. Therefore, don’t just do this type of work for your actors/characters. Do it for your locations as well. You never know what background you may want to use, and the more shots you take, the more options you will have.

Of course, all this requires thinking ahead. But you will be glad you did.

Found this post informative? Check out David’s advice on Developing Key Art as your film enters the festival circuit.

David Averbach December 21st, 2012

Tags: film marketing, film posters, graphic design, key art, Photoshop, set photography, The Film Collaborative, unit publicist

Rethinking Your Key Art Game Plan, Part 1

Over the next several weeks, The Film Collaborative’s Creative Director, David Averbach, who has worked with dozens of TFC Clients and other filmmakers to help them create and refine their key art, will talk about ways you can avoid the problem of finding out all too late that you don’t actually have the proper materials to produce the key art you want to make.

Note: This Key Art series is intended for micro-budget filmmakers whose crew is not under a union contract. If your film’s crew is under an IATSE contract, you will need to abide by the rules regarding still photographers on set as forth by the union. We have been advised that there may be penalties involved by bringing an intern or PA in to shoot stills.

See Part II HERE

Takeaway: For narrative feature films, understanding the technical aspects of producing key art and thinking ahead to your key art while on your film set can save time, money and a heck of a lot of aggravation down the line.

If I had a nickel for every narrative feature filmmaker who has told me that they got a photographer, professional or otherwise, to come to their film set and shoot photos but in the end they didn’t show up or didn’t do a good job, or was only there for one day out of a sixteen day shoot, and therefore there was nothing to show for that effort in terms of producing images that could be incorporated into a poster, and therefore were only really left with the prospect of using frame grabs from their film, I’d be rich I could probably buy a Starbuck’s gift card that would last me a week or two.

I hope this series of posts can offer some helpful suggestions for you to avoid this situation for your next film.

First let me say that while I design movie posters, I don’t really have a background in filmmaking itself. If there is anything incorrect/inaccurate, generally unfeasible included here, or if you have anything you think I should add, please feel free to let me know. That said, it’s clear to me that in the heat of the film shoot, filmmakers often forget to think about or are so focused on the film shoot that they can’t get around to thinking about the art they might need to support a variety of possible marketing ideas and concepts, and are therefore down the road left with fewer choices and placed in an ultimately weaker position vis à vis possible options on how to market their film or sell it to a potential buyer without an expensive and inconvenient reshoot. (I’m working under the assumption that you are the type of filmmaker who has neither endless funds for a photo shoot 6 months after your shoot ends nor the energy to pull in yet another favor from some photographer you or one of your colleagues may have worked with in the past.)

There are two parts to tackling this problem. The first has to do with understanding resolution: what you have, what you need and how to bridge the two. The second has to do with beginning to think about your marketing strategy even before your film shoot, and preparing to build the raw materials you would need to execute any number of possible marketing directions.

So let’s talk about resolution first. (I’ll get to marketing strategy in Parts 2 and 3 of this series).

Knowing the resolution of your frame grabs

If you’re lucky enough to work with a 4K or 5K camera, such as a RED camera, meaning that the max output resolution is over 5000 pixels wide (5120×2560 on a RED) (which is about 6.5 times that of 1080p (1920×1080), those will produce beautiful film stills. So if you were to shoot your entire film in 5K, much of this next part won’t apply to you. In the real world, according to my DP friend, most people don’t and can’t afford the drive space and rig to do that in production. So if this is the case the highest output for a film grab might still be 1920×1080.

Now 1080p cameras that have a good quality and large sensor with a full chip (DP friend: preferrably not a 1/3 chip), will produce beautiful images…wonderfully clear, and of course you can blow them up to a certain extent without anyone noticing. But if you want your image to take up most of the width of your poster, you will have a resolution problem. The bottom line is, with 1080p output, if you want a theatrical poster using just a few main images, you won’t be able to really rely on frame grabs alone.

While frame grabs will probably work just fine to produce the key art for a DVD cover or a digital release, they are simply not going to cut it for a one sheet. And even while some films will never end up getting a proper theatrical release, all filmmakers tend to want a theatrical (sized) poster, especially if their film gets into a top-tier film festival.

Why won’t frame grabs work well? Well, Bill Clinton said it best: arithmetic.

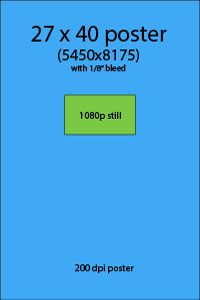

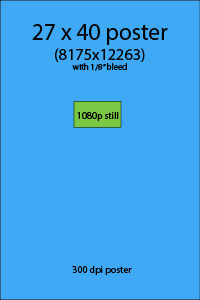

Perhaps not every filmmaker knows how 1080p correlates to print resolution. As I state above, something that is shot in 1080p (16:9 aspect ratio) is 1920×1080 pixels in dimension. How many pixels will you need for a poster? Well, posters are usually 27×40 plus a ¼” bleed, and the minimum resolution is about 200 dpi (or dots per inch). That means that a poster needs to be at least 5500 pixels wide and that a frame grab would be up-res’d be almost a factor of 3 in order for it to stretch horizontally on a one sheet to even get up to 200dpi.

|

|

Until all cameras are 5K resolution and one can easily shoot their whole film this way, part of the collateral damage from the transition to digital is that this is yet one more thing that a filmmaker has to think about…in the days of 35mm, it was common practice to pick a frame of the film and scan it into a large still for use in a poster, but if the maximum output or effective maximum output from your camera is 1080p, you don’t have that luxury.

The end result will produce a blurry image at best and a pixelated image at worst. While this might be good for a background image, if you would like to use a close-up of someone’s face or a full body shot, this is just not going to look good.

Now that we’ve agreed that we need still photographs, what steps can you take to ensure that you will get something that you can use, both in terms of quality and content?

How to make sure you have images for key art—no matter what your budget

You are shooting with a great camera that can take great stills. But what if you can’t spare the time to use the camera you’re shooting on to also do stills?

On to Plan B. Hire a professional photographer, or at least someone with a really nice camera. In an ideal situation, you would get another 5D to take stills to complement the main motion picture camera. (Per my DP friend…Snug up to the lens…use Zeiss prime lenses for sharness or Canon L series lenses if going for more of a softer thing. If you can’t do that with your budget, use a monopod and critically check focus). This is great advice. If you have the budget for it.

But creating images for a poster is more than just producing nice photos. Shadowing the film shoot with a still camera often produces shots that are great for press stills, but may not be all that useful for a poster. Of course it depends on what kind of poster you will want to make. But in the end, it’s good to have a Plan C, and not in the sense that you need a third option because the first two didn’t work. I mean a concurrent Plan C.

This is it: Think of shots for key art as publicity shots, not as enlarged film stills. (And by “publicity shots,” I don’t mean for the actors, I mean publicity shots for the characters, so make sure they stay in character while you shoot them.) It’s fine to do what my DP friend says, but you need to do more. There’s lots of down time on a shoot. Actors are present and in costume and makeup. Move away from the action of the film. Use that hired photographer. Or use hire an intern with a good eye. Use that second 5K camera. Or get an inexpensive 16 megapixel camera. It doesn’t really matter. Just do it. Start outside around lunchtime, when the light is best. Find a white wall, or hang up a sheet outside somewhere. Think about what kind of poster you’d want to make. Develop half a dozen concepts (more on this in parts 2 & 3). Take it seriously. Start shooting.

What you should be creating here is this: Hi-res Scraps. You don’t know how you will use them, but at least you will have something.

Don’t have the budget for a second 5K camera? Fine. But we’ve gotten to a point where consumer cameras can actually produce extremely high quality and high resolution images. Last year, I bought this point-and-shoot camera on Amazon. It’s 16.1 megapixels. It lists right now at $150, but I think I bought it for $109 at one of those after Christmas sales. Every filmmaker has the budget for this much. You’ll be paying a lot more to correct this down the road if you feel this will put your budget over the edge.

See how much more you can get in terms of resolution when using a 16 megapixel camera as compared to a frame grab?

Is this a crappy camera? Compared to the ones you are using to film your shoot, absolutely. But graphic designers have their bag of tricks. Perhaps you’ve heard of Photoshop? We can make even images from these cameras look great. If the right shots are taken. So now there is no excuse to come back from a film shoot empty handed in terms of images for your key art… It is like buying key art insurance: you may not need to use it, but in a pinch you’ll be glad you have it.

Next week, in Part Two, I’ll give you some examples of a few concepts every film should have their “key art still person” shoot.

David Averbach December 12th, 2012

Tags: film marketing, film shoots, images, independent film, key art, One Sheets, Photograhers, posters, resolution, stills

Premiere to Release-Why does it take so long?

Written by Orly Ravid

Now that Sundance has announced its new line up, it seems appropriate to discuss the issue of a film’s distribution after premiering or acquisition at festivals.

It is often the case that films do not get released until 6 months to a year or even more from when the film had its festival premiere…At least this is the case when traditional distribution is pursued as opposed to planning the distribution and marketing to coincide with the premiere and work off that plan accordingly.

Here are 10 reasons for the delay in time between a premiere launch at a festival and traditional distribution into the marketplace:

1. The time it takes to find buyers. These days the market cycle is longer than it’s ever been. Sometimes even a year after a festival or market, sometimes longer to sell titles. It’s a buyer’s market, so few films enjoy the pleasure of contested bidding that forces prices up and faster closings. Sundance, of course, is one of the few festivals that commands such a dynamic and more films than at most other festivals will secure distribution, at least domestically, as a result of premiering there.

2. Once a deal is closed, then there’s the contract and delivery which takes time… months sometimes.

3. Long lead times for press are required, at least four months, and that planning usually does not happen until after deal closure.

4. The distributor needs time to find open slots/appropriate slots in the calendar for theatrical – and it’s competitive out there so getting a booking takes time, and getting the right one for the film takes even more time, again, months. Sometimes even 6 months is needed to book the right theatre for the right time.. Some of the best screens are locked in well in advance.

5. Cash flow is needed to launch marketing campaigns. This can be an issue for some distributors. Recouping some revenue from previous releases will be needed in order to fund future ones.

6. Major digital outlets take several months to upload and make a film available. Cable VOD has solicitation windows. DVD and digital also require set up times and announcing the title and marketing it ahead of time so again months of planning and slotting. One wants to be strategic about release time.

7. The time of release is sometimes specific to the film. It may be theme driven and demand specific timing or it may want to avoid direct competition. Also inventory shifts in retail stores dictate the optimal time for DVD release (ie. certain times of year, like Christmas or Halloween, call for more of a certain kind of film).

8. Internal scheduling of the distributor. As you know, distributors will have other releases that they need to navigate given what their key outlets have planned.

9. Grass roots and other marketing also demand lead time.

10. Overall, the difference between DIY and traditional distribution is that in DIY, you can plan months in advance to set up the outlets and use the press attention at a festival premiere to catapult the film into the market, even if you aren’t 100% sure which festival will be your premiere. Having everything in place to pull the trigger when you get that acceptance puts you in a good position to release. In traditional distribution, the distributor cannot do advance planning and so the planning starts after the initial buzz has been created at the festival.

I know some of you have been confused or frustrated by the lag time between a festival premiere of a film and the release. Hopefully this helps to explain the matter.

Orly Ravid November 30th, 2012

Posted In: Distribution, Film Festivals, International Sales, Uncategorized

Tags: cable VOD, DVD release, film distribution, film promotion, film sales, independent film premiere, independent film release, Sundance Film Festival, theatrical release, traditional film distribution

The State of International Sales for Independent Films

In our continuing look at film sales, today we are featuring an interview with an international sales agent for independent films, Ariel Veneziano of Recreation Media. He has handled international sales for many films including the highest grossing documentary of its time Michael Moore’s Bowling For Columbine, the highest grossing independent film of all time Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, and America’s most watched television show CSI: Crime Scene Investigation. The Film Collaborative works closely with Recreation Media for its international sales efforts.

SC: How are things different now than they were 5-10 years ago?

AV: In one word: worse. Sorry to start this off on a down note!

SC: Do you mean money-wise or just sales interest at all?

AV: I think both. It is best to acknowledge what the reality is. At the same time, there are some opportunities that have emerged, new ways of doing business that didn’t exist several years ago. It is important for filmmakers to have a reality check that there have been changes in the way viewers consume media and that has led to radical changes in the market. People go to movie theaters to see independent films much less than they did. Although global box office appears higher, this is only for a very small percentage of films. We’re talking Twilight, Iron Man, Dark Knight, James Bond. That share of the box office numbers is cannibalizing all of the other films out there.

Home entertainment revenues have been shrinking. DVD is progressively becoming marginal, and while broadcasters are multiplying, the license fees they are paying, especially for independent product, are getting smaller. While VOD and digital distribution are on the rise revenue wise, there is also an overabundance of product being made because of the sudden availability of low cost production methods.

Piracy is a threat to revenues. People still watch movies, but they don’t always pay for them. There is now a generation who sees this like going to the faucet and turning on the water, you don’t pay for every glass you fill. You pay a monthly fee and you can get a lot of water. Same with many internet subscriptions, one fee, unlimited choice. The good side to digital and particularly online distribution is the ability to, in theory at least, reach a broad audience without need for a large infrastructure. Are there ways to capitalize on that trend? Yes. Are they easy? Not necessarily, it is a very fast moving situation and even the so called experts who have done this for years, they don’t know what is going on. There’s a lot of chaos here, the wild west.

SC: If we were to look at 5 years ago, what would have been a pretty normal deal scenario for an independent film with no names, but some festival pedigree?

AV: If we’re talking about one of the major festivals, like Cannes, Venice, Berlin that you could put on the poster, those are the big 3, you could have made several hundred thousand dollars in worldwide sales. But that’s not necessarily the case anymore.

SC: Right, I was noticing out of Toronto in September that films with more than notable names were being picked up in groups for $5 million, when their budgets must be nearer to $20 million combined. Lionsgate/Roadside Attractions bought Stuart Blumberg’s “Thanks for Sharing,”(Gwyneth Paltrow, Mark Ruffalo, Tim Robbins), Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini’s “Imogene” (Kristin Wiig, Annette Benning, Matt Dillon) and Joss Whedon’s “Much Ado About Nothing”, all of them for a reported $5 million. So those films are not making their money back in advances. It used to be you could be made whole or close to it, but now that is not nearly the case.

AV: Right, it means you have to be smarter with the budgets, keep them low. Smarter with the finance plans and use soft money, something that isn’t going to be high risk for investors. What happened in the music industry is now happening to film. When is the last time you bought a CD? With technology progressing so fast, storage capacity growing, speed of transmission of data, availability of mobile devices. Few people are going to want a DVD collection, why? I can access a gazillion movies in my cloud storage. So if people aren’t really spending money on music, the revenues for albums have gone way down. Why would they continue to spend for films? If you want to know what the future holds for the film industry, look at the music industry.

And because there is so much uncertainty, buyers are trying to safeguard themselves. They are being much more particular about titles they take on and for what prices because they don’t know how well it will sell.

SC: So when you go to a market, what attracts their interest to buy anything?

AV: Bigger theatrical pictures. For foreign buyers, they want to know the film will have a wide domestic theatrical release. Some domestic distributors can promise that like Weinstein, Summit, or if you are an international sales agent who struck a deal with a studio early on to release the film with a minimum 1000 screens, buyers are receptive to that.

Cast of course makes a difference. Certain genres like action do very well. Everything related to action travels well. So, adventure, sci fi, thriller, fantasy are all cousins of the action genre and those typically do well.

SC: One genre I see a lot in indie film is the “coming of age” drama story. How well does that kind of story do?

AV: AWFUL in terms of revenue. I am talking as a businessman. As a viewer, I love coming of age dramas, but I can’t sell them. Nobody wants to buy them unless: 1) it is directed by a world class filmmaker. If it is a Woody Allen or Terrence Malick film, you’ll sell it 2) big names in the cast and when it comes to getting buyers excited about the cast level, the bar has gotten a lot higher as far as this 3) based on a best-selling novel 4) selection in a MAJOR festival. For international revenue that would be Cannes, Berlin, Venice. Sundance has an impact domestically, but internationally people don’t care. Toronto the same, it is fine for a repeat screening, but if that is your only claim to fame, not going to help you that much.

Coming of age drama is one of the worst for travel; that and comedy. Buyers just flee unless it comes with any or lots of those 4 criteria. So Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life, fits 3 of those criteria. World class director, A level cast, major festival selection. That is desirable to buyers.

SC: So you are really saying that a microbudget indie film with all of those things absent really has no chance for a buy at a foreign market?

AV: None. Absolutely zero.

SC: This is good to know, we’re tempering expectations here. This doesn’t mean there is no audience for the film. It simply means that it has no value to a buyer.

AV: It is going to bring in too little money for them that it isn’t worth investing in. But you’re right, does it mean you can’t put it on iTunes or some other online outlets on your own and get people in foreign countries to pay to see it? You can absolutely do that. But since it is such a wild-west scenario at the moment, the revenue could still be zero for you.

SC: Are you saying that there are no prospects even in broadcast for this kind of film?

AV: No prospects, but as with anything there are a few exceptions. A Lifetime movie, like a women in peril kind of film. If it was bought by Lifetime in the US, then there could be some broadcast value elsewhere. But that is a very specific kind of film, very formulaic.

SC: What about a low budget documentary? What if it was picked up by HBO in the States?

AV: Now we’re mixing types of films. Docs are a little bit different, but it depends on what they are about. If it strikes the right chord with something timely, you find the right broadcaster who is filling their schedule with a thematic type of programming and your doc fits that profile, then boom you have a deal. A small deal probably, but still a deal. A theatrical doc is the exception, docs are mostly for TV. Having it on HBO? No, it doesn’t make a difference. Not PBS either. It is more about the right subject matter, being topical.

The brands broadcast buyers respond to for narratives are Syfy Channel, Lifetime, Disney, Nickelodeon, maybe Hallmark. Again, those films are very specific and formulaic. No fancy effects, no flashbacks and weird montage, just very straightforward stories.

SC: A foreign sales agent does what? You go to markets, but what is done in between? Should I get a specialist foreign sales agent or a worldwide sales agent?

AV: Typically domestic and foreign markets are two different animals. There are some sales companies that can act as a good one stop shop, handling both within the same company and that can simplify administration. But the option to hire a dedicated domestic sales agent – also known as a producer’s rep – is a common way to go as well.

What we do as a sales agent is that we help you maximize revenue on the film from all available sources around the world. So that entails marketing, highlighting an existing campaign or creating a new one; working the press, getting a film into the right festival. Then leveraging the relationships we already have with buyers around the world. Negotiating and papering the deals. Delivering the movies. Invoicing and collecting the revenue. Monitoring how a film does in a territory and requesting (or demanding!) the revenue reports. Structuring the deal correctly so you can have some money up front and then see more money later down the road – if the film does well. It is a “technical” job and is very relationship driven.

Probably the most important aspect for a filmmaker in electing a sales agent, is working with someone you can establish a relationship of trust with. Trust can be an elusive thing sometimes. You keep hearing stories about filmmakers being ripped off by sales agents. Some films are probably not meant to be handled by a sales agent because it is just too many layers of middlemen for too little available revenue, and the filmmaker would have been better off handling it themselves for the amount of sales revenue that can be gained from it. It will be a lot of work though for the filmmakers and some people are very naïve about that, thinking ‘oh who needs a sales agent?’ and they take their film to markets or put it up for sale themselves online and at the end of the day, a lot less revenue comes in than they thought. It is a lot harder to make money than it seems…

SC: Sometimes filmmakers try to call buyers and they find their calls aren’t returned. Buyers don’t know who they are.

AV: Trust me, sometimes we have trouble getting them to return our calls too! And they do know who we are.

SC: What is the typical length of time for a sales agent agreement?

AV: There are two types of agreements. One is a straight distribution agreement where the sales agent comes on just to sell the film into territories. Another is when a sales agent comes in with a minimum guarantee, some money upfront. If they put in some money, they will be more demanding on the terms. If it is just straight distribution, the filmmaker has more leverage to negotiate it. So a typical term is 10-15 years.

SC: Why does it need to be that long?

AV: Well there are two questions here. The first is the sales agent’s engagement term. How long is the agent going to be selling the film? And the second is for how long is the agent allowed to sell the rights? How long will the contract last for each deal brokered? I might sell the film to a buyer in the first year, but the buyer might want a 20 year contract on that film especially if it is an all rights deal where they can exploit each window over a long length of time. They might spend a lot of money to release the film theatrically and make up the bulk of that money on DVD/VOD and then digital then broadcast which can then mean relicense and relicense over a long period of time. You know, when you watch TV, there are rerun movies, things that came out a long time ago. Those have been relicensed over time. So if you are going to all this effort and expense, you want to have a long period of revenue coming in on that.