Developing Key Art as your film enters the festival circuit

How much to spend on developing key art, and when to spend that money, is one of the many important decisions a filmmaker has to make. Yet like many aspects of the filmmaking process, there is no one-size-fits-all standard. When we were discussing the prospect of my writing this post, one of my colleagues at TFC remarked that for a film that costs, say, $250K to make, a $10-20K or more spend on developing key art (and mind you, this is separate from a marketing budget where you have to pay to get that key art out into the world, and separate still from designing and maintaining a web site) is not unreasonable, assuming one wanted to hire a top agency. Other filmmakers get someone they know to do it for free, if for no other reason than they are out of funds. Most micro-budget indie filmmakers will undoubtedly fall in between these two polar extremes in terms of what they will end up paying, but in the end, what you produce, and when you produce it, is a decision that should not be rushed or taken lightly.

Most filmmakers would agree that good key art is essential…it can be the factor that decides whether somebody will click further to watch your trailer, or move on to another film. If it is carried over to your website effectively, it should inspire confidence in your brand. Good key art can endure and even come to possess an iconic existence of its own that will represent with your film for years or even decades to come.

But good key alone is probably not going to work miracles. If your trailer, website, official reviews, or word of mouth is disappointing, or if insufficient marketing prevents people from even knowing that your film is out there, hiring a top creative film and spending that $10-20K at the expense of everything else doesn’t make any sense. So while key art is too important to take short cuts on, its value won’t be fully realized if the rest of your budget cannot support it.

So let’s say, for the sake of argument, that you don’t have that 10-20K or more lying around for key art. Now, I have worked with dozens of filmmakers to either design (or consult with and/or assist them in developing) their key art. When I have an initial discussion with a filmmaker, I can tell right away which clients probably don’t even have $1K to devote to their the key art. How? Because the first question they ask me (after they see samples of my work) is how much I would charge to produce a poster.

This question always surprises me, especially when it comes from filmmakers for whom this is not their first film, because it reminds me that filmmakers often do not ask the right questions when producing key art.

For example, how can I give them a quote without knowing what shape is their art in, how much time it is going to take to get up to speed about the film…watch it, discuss it, understand it, determine what is possible based on the art that they have, come up with several different directions and mock them up, fail a few times until we come up with something we like, and then go through several refinement stages, figure out printing, cost, logistics? And this doesn’t include mocking each possible direction to pixel-perfection, uprezzing, retouching, or producing style sheets or ancillary artwork, like a top agency would do.

Not appropriately accounting for key art development (and overall marketing strategy) as a line item in their film budgets forces filmmakers into a situation whereby they can only order the services that will fit their budget, rather than coming from a place of asking what will be best for their projects.

So we go through this dance of whittling away steps to cut costs, and in the end, I provide only a range based on an hourly rate, with phases built in, so we can periodically access if we are going over our budget range. This way, how many hoops I jump through will ultimately be up to the filmmaker as we move through the collaborative process.

Another important thing to remember is that you can’t always determine the cost of developing a piece of key art just by looking at it. Oftentimes, the prevailing concept itself might not look all that expensive to produce, but you never know how many twists and turns were required for the creative team to reach that final product.

So, how can a filmmaker get back to asking the right questions?

Producing key art is about ideas and talent, good photography, and a solid understanding of one’s film and how it fits into the marketplace.

It’s also about patience.

This is a scenario we have seen more than a few times: let’s say your film gets into Sundance or Slamdance or Berlin or SXSW and you are racing to finish your film. You haven’t budgeted all that much for key art in the first place, but you feel like you need something to show at the festival. You have a website, but it’s the one that’s been up since your crowdfunding campaign, and it’s not all that pretty. What should you do?

Certainly, there is no one right answer. We have seen filmmakers produce amazing things in a very short amount of time. On the other hand, we have seen other filmmakers really fail miserably, and actually do their film a disservice by making too many decisions too quickly.

But let’s say your first instinct it to produce a poster. Your second instinct should be to make sure your first instinct is correct.

DO YOU EVEN NEED A FULL-SIZE POSTER?

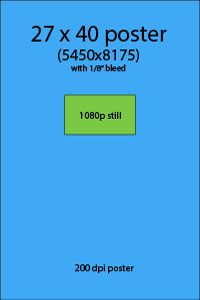

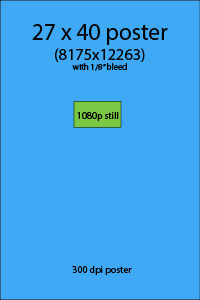

Posters are, technically speaking, quite hard to produce if you don’t have the right art. I’m talking about resolution.

Last year, I wrote a series called Rethinking your Key Art Game Plan, where I discussed the technical requirements for producing a standard 27×40 (or 27×39) inch poster. In particular, I noted how pulling stills from a 1920x1080px master isn’t going to produce enough resolution for a poster, unless you are going for a grainy or blown-out look. These days, more and more filmmakers are working with 4K cameras, which helps quite a bit in this area.

Yet while using 1920×1080 stills to promote your film may not be ideal for a poster, they are perfect for other uses. For example, you can produce 4×6 postcards or a great website background. These might actually reach more people throughout the festival as a whole than a poster that merely hangs for a few hours in a marquee lightbox on the day of your screening.

Title Treatments

Create a proper title treatment using a vector-based program such as Adobe Illustrator, turn it into an Outline shape (rather than editable lines of type), and save it as an .eps file so it can be reproduced consistently.

(If you didn’t catch all of that last part, just convey to your designer. If your designer doesn’t get it either, hire a new designer.)

Another dilemma we’ve seen filmmakers run into is that they only have very limited still photography at the time they enter the film festival circuit, and don’t have the time or budget to do a photo shoot. Rather than force these images into a full-size poster that you have mixed feelings about, it might be better to take frame grabs from your film and produce something that’s 1440x2100px (the size needed for iTunes…VOD art generally needs to be 2:3 proprotions) and that you are satisfied with. This size would also be OK for a 4×6 postcard. You can worry about a 27×40 poster later.

Alternatively, many filmmakers simply brand a few press images from the film with their title. Work with a designer to create a great Title Treatment (the design of the title of your film) and brand the film that way, so there will be consistency when you do swing back to the key art.

SHORT-TERM OR LONG-TERM KEY ART

But let’s say you do have the art to do a full-size poster. There’s still a question of whether you design for the short term or the long term. More and more films are being released digitally without much theatrical play. Moreover, what you produce for a theatrical may not even be suitable for VOD. A panel at IFP last fall addressed this exact question, and there was apparently much disagreement:

“This panel drove home several completely contradictory messages, all in the space of one engaging hour. The first was that now you need more art than ever, to keep your audience engaged through daily social media updates both before and after your film is released. The second was that films should adhere to the same few images, so that they become recognizable brand markers. What’s a filmmaker to do?

[…]

Another catch-22 discussed during the panel was VOD vs. theatrical art. As much as it benefits a film to project a singular identity, it’s rare for a single design to suit both purposes well.

The experience of viewing a poster inside a lightbox at the theater is very different from the experience of browsing titles on Netflix, and key art must adjust accordingly. Besides the obvious (smaller space, bigger images) the VOD art typically focuses more on celebrity, genre, and easily conveyed aspects of the storytelling.”

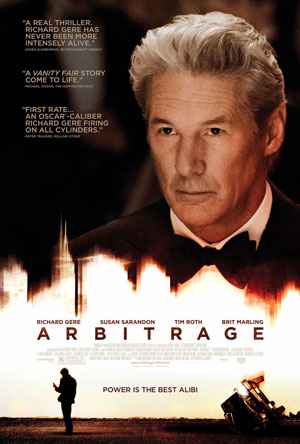

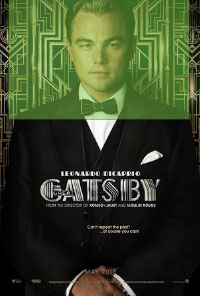

They provided the following graphic as an example of the differences between theatrical art and key art for VOD.

Sawyer Studios Theatrical vs. VOD Digital Art Slide

It is quite clear that the some of the theatrical posters do not work very well for VOD. But I am not convinced that at least some of the VOD posters here could not have worked for theatrical (apart from the fact that a few of ones for VOD are just plain bad). These days, even as one is doing a theatrical, the same poster can be seen all over the Internet, and perhaps on postcards too. So whatever you produce, you should think about how the image looks when it is viewed at a variety of sizes, and pay special attention to the iTunes size and the Netflix size.

Perhaps the designers of the theatrical posters in this graphic did not consider this when they were designing. (Or perhaps a marketing team came along and wanted something else for VOD.) The point is, think as far ahead as possible and aim towards producing key art that will work for both theatrical and for VOD. Because if it does need to be redesigned, there’s a good chance that you will be the one paying for it, one way or another.

THE HIDDEN COST OF USING POSTERS ON THE FILM FESTIVAL CIRCUIT

Many of you know that TFC also offers Festival Distribution as one of our services. We get asked all the time for posters. Sometimes three, or five, are requested. But we generally do not send them for every festival. Here’s why:

Digital Printing

Printing fewer than 15 posters

We have used Uprinting in the past and recommend them for one-off digital printing.

So let’s say your film gets into Sundance or Slamdance and you need to print a few posters. You can get 3 posters printed and sent directly to the festival for $80. That’s not going to break the bank. But if you commit to doing that for every festival thereafter, you must be prepared to lose at least $40 (the cost of 1 to print and ship) of your festival fee each time you book somewhere.

If you are thinking that you can simply print a bunch of posters and send to festivals yourself, there also a few things to remember. First, poster tubes cost money (although Fedex will supply their own packaging, but their shipping rates are expensive), and when all is said and done, mailing them yourself doesn’t cost all that much less than having a printer ship directly. Believe me, I’ve tried.

Offset Printing

Printing more than 100 posters

America’s Printer has always done a great job for us with 4 color printing, and can even ship them individually for you.

In terms of printing, you also may not want to order too many at once (for example, you can have them printed in 4-color offset printing in quantities from 100-1000, which will cost $600-$800 ) because you will undoubtedly want to add additional laurels (for art house films) or awards or even quotes to the one sheet as you get further into the festival circuit. Printing too many will lock you into something you may not wish to use forever. But printing as few as 30 digitally will cost as much as printing 500 using an offset printer, so there’s a bit of a “doughnut hole” here.

And many filmmakers just don’t have that much loose cash to spend.

Our recommendation is to only get a large quantity of posters made if you have a theatrical. In the meantime, you may want to limit the festivals to which you have posters sent to Industry festivals where buyers are present. For the other festivals, supply them with a link to the hi-res version of your one-sheet: many festivals will print on their own. This is especially helpful for international festivals. They may not print larger as large as 27×40, but at least the cost comes out of their budget, not yours.

TIPS ON LANDING ON THE RIGHT CONCEPT

I was asked to write this article to address the question of how one decides on the best visual representation for one’s film. In other words, what should you put in your poster?

The short answer is, there is not just one answer. You can ask 5 different people and they might each tell you something slightly different. But let me try to break it down with a few tips.

- Whatever you do, it should be polished and look like some thought was put into it. You would think that I’d be setting the bar a little higher as the first tip. But no. If someone whose film were premiering at a A- or B- list festival showed me the their poster, and it looked like the VOD poster for Arthur Newman or The English Teacher in the graphic above, I would tell them to either scrap it and start over, or to leave it at home.

- Know your marketing strategy before you start designing. I could write a blog just on this topic. More than one, actually. The number one problem that filmmakers have in this regard is that they are too close to their own film. So first, it’s important to talk to your team, and to others outside your team (shameless plug alert: also a perfectly good thing to talk about when you are consulting with TFC via one of our membership packages) about where your film fits into the market and who is going to be buying it…literally…which distributors, which niche market. If you feel that your film has crossover potential to a second niche audience, find a way to cater to both, but don’t dilute the message to serve two masters. Make sure you have the art to support whatever strategy you come up with. A designer can help you evaluate this, but this whole process might have to be repeated if the art comes up short. The task is for buyers to see the market potential. If you feel like a concept “cheapens” your film, don’t dismiss it completely until you’ve talked to somebody who can give you some perspective. Take your time and don’t rush. Build your brand thoughtfully. You are making key art to sell your film, not so you can hang a cool poster in your office.

- Hire a real designer. Don’t just get someone who knows Photoshop to do it for you for free. Make sure there is budget for this before you make your film. Ditto a web designer. Get someone who knows the industry. Someone who will watch your film and discuss ideas at length and who can at least talk through several directions with you before committing. Loop this person into the market strategy discussions.

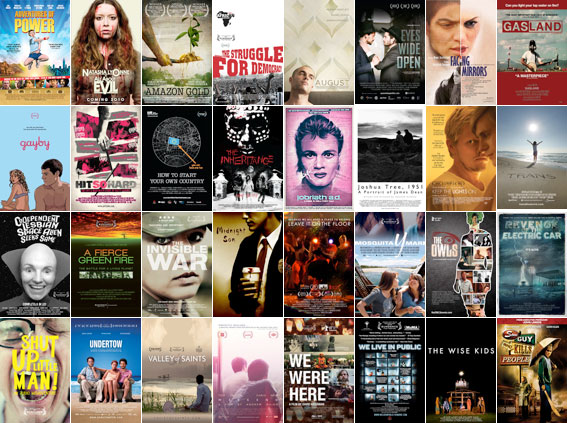

- Your art should stand out but not be too obscure. What do I mean by this? Two tests: (1) Get a reality check—before you brainstorm, take a look at the artwork in the Criterion Collection. This is an example of what NOT to do. These films are mostly classics that are being rebranded in a pretty pretentious way. It’s fine for them. But not for you. You do not want to make a poster like this. Maybe some day. Not now. (2) Take the key art that your designer mocks up and paste it in a screen shot of the iTunes Store in the “Independent” genre (or a more specific genre in the store). Make it look like it were in the store already. How does it stand up? Would you notice it? Is the title completely readable? Would anyone recognize that *one* slightly recognizable star you have in your film at this size?

- Look at existing key art in the genres your film is attempting to target. Grab these poster images off the web, and give those to your designer as a reference. For certain type of films, it’s OK to be reductive. Others, you’ll want to be more original. For example, for docs and horror, go for originality and/or quirkiness. For foreign language narrative films set in exotic locales, go for scenic beauty plus audience identification with the protagonists. For LGBT films, go for sex or edge. For non-LGBT narrative films, put the most famous actor you have on the poster. For comedies: it better be amusing. For romance: it better be romantic. For thriller: it better thrill. Some of this seems obvious, but it also can be a lot easier said than done. There is no one right way, but there are many wrong ways. It’s important that you know what those are.

- Make a great trailer to go with your art. Hooking them with a poster does no good if the trailer they watch right afterward underwhelms. Think about your niche when producing this trailer. Think about how your poster gives folks a preview of what they will see in the trailer, and then exceed their expectations. Produce a trailer that’s PG. You can also produce another one that’s not, but you will need one that has no nudity, curses, drugs or sex toys for digial platforms. So now you’ve been warned. Encorporate your Title Treatment into the trailer to tie in your branding.

Another reason to take your time with your key art: use it as a way to get your audience involved. Maybe they haven’t heard from you since your Kickstarter campaign. Maybe you’ll pick up some Facebook fans at your first couple of festival screenings. Why not find a creative way to create a dialogue with the people who are supporting you?

As I stated at the beginning of this post, you will encounter a lot of opinions out there along the way. And “success” when it comes to key art is nearly impossible to measure objectively…is your campaign successful if people like it (even if they don’t really love your film)? If a buyer ends up using it? If your film does well in the marketplace? While there are many films that industry peeps can point to and credit key art for that film’s success, the vast majority of films will not fall into this category. Nor will they be offered a 7-figure deal from a major studio at Sundance. In the end, though, one of the toughest transitions a filmmaker has to make is the switch from proud parent to business person. Put yourself in the mindset of someone who knows nothing about your film: does the key art you produced really make people want to see your film? And will they even remember your brand when the time comes when they actually can see it? Everything else, as they say, is crap.

David Averbach January 8th, 2014

Posted In: Key Art

Tags: artwork costs, Film Festivals, hiring a designer, iTunes, key art, Netflix, postcards, poster sizes, posters, The Film Collaborative, theatrical vs VOD, title treatment

Rethinking Your Key Art Game Plan, Part 2

Guest blogger is The Film Collaborative’s Creative Director, David Averbach, who has worked with dozens of TFC Clients and other filmmakers to help them create and refine their key art. See Part I HERE

Note: This Key Art series is intended for micro-budget filmmakers whose crew is not under a union contract. If your film’s crew is under an IATSE contract, you will need to abide by the rules regarding still photographers on set as forth by the union. We have been advised that there may be penalties involved by bringing an intern or PA in to shoot stills.

Last week, in Part 1 of this blog series, I discussed how relying solely on 1920×1080 pixel frame grabs was a bad idea if one wanted to create a poster that featured some sort of main image. In an ideal world, your entire film would be shot on a 5K camera, and you could pull as many frames from the footage as you wanted. That would be Plan A. But in the real world, many filmmakers emerge from their shoots with only 1080p frame grabs, and that’s not going to work.

Another problem is about marketing. During the chaos of a film shoot, filmmakers often forget to think about the art they might need to support a variety of possible marketing ideas and concepts, and are therefore left with fewer choices and placed in an ultimately weaker position vis à vis possible options on how to market their film without an expensive and inconvenient reshoot.

This blog series offers some concrete advice on how you can protect your film’s marketing future by adding a few inexpensive steps to your key art game plan.

A photographer on the set with a second 5K camera is great if you can afford it. That would be Plan B. But if your budget is limited (or even if it isn’t), last week I suggested a third plan—a “Plan C”—that as far as I’m concerned should be executed whether your film is entirely being shot on a 5K camera or whether there is a professional photographer on set or not. I’m sure I made some of you cringe by suggesting that you pick up a cheap but powerful point-and-shoot camera and putting an intern or production assistant in charge of shooting “hi-res scraps”—basically a lot of shots of the characters in various poses during the down time on a film shoot—that can be utilized down the line by a designer to execute the envisioned poster. The bottom line is this: as a designer myself, I’d rather have the opportunity to work with shots taken from a cheap but decent camera than nothing at all.

One of the reasons I suggested this is that while professional photographers undoubtedly bring a great deal of talent to a set, their exact skill set may not be entirely conducive to producing key art elements. A photographer’s eye for composition usually relies on what they see in bounds of their view-finder, and having them do some of the things that I’m going suggest here in Part 2 of this key art blog series may cause a bit of pushback and confusion. It’s best to let them do what they usually do and concurrently (i.e. Plan C) have a go with the point-and-shoot/intern thing. Of course you don’t have to use a point-and-shoot camera if you have a better one available. But I work with a lot of filmmakers whom I feel would find an excuse not to do this if there were more work/more cost involved. And if you use an intern or a production assistant, or perhaps a rotate through a handful of them, you’re giving them something real to do, which will inspire them to do a better job in everything they are their to do for you. It’s a win-win. Have them take as many photos as they can. Just make sure you buy some extra high capacity compact flash cards.

Now onto Part 2…

You may have an idea of what you want your poster to look like even before you begin your film shoot. Great. But don’t plan for that to be the only idea you execute. You should produce the photos necessary to execute MANY ideas. Here are some possible concepts.

Have a discussion about marketing before your shoot and come up with two dozen ideas. They don’t have to be all that specific. If your film involves one main character, or a pair of characters, then let’s assume for the moment that you could feature them in some way in terms of poster real estate…Accordingly, my first example will be to think a bit about how you could execute a concept that features a single image that takes up the entire poster. Again, you decide what that single image should be…perhaps it’s your main character. Perhaps it’s two characters. Perhaps it’s something else. But here’s the takeaway: at this stage, don’t produce a shot. Produce ELEMENTS.

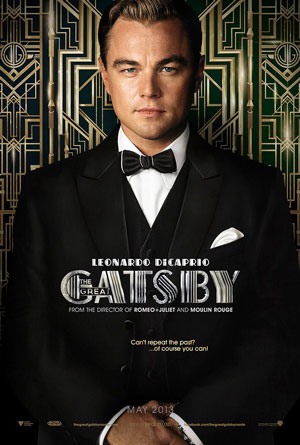

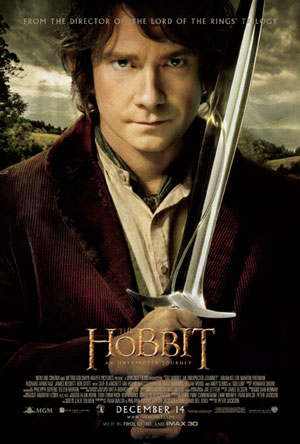

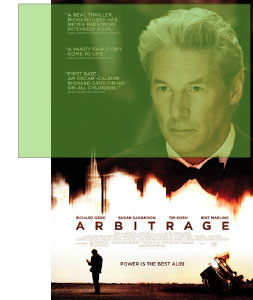

Let’s have a look at a few posters from current movies that involve a single shot. If these movies aren’t your taste, it doesn’t really matter…the concepts can be applied to almost anything or any style of poster.

|

|

|

Looking at these posters closely in as full a resolution as I could find online, they have one thing in common: each image of the actor is a cutout placed in front of a different background from which the shot was taken. Artbitrage is the most blown-up…if you walk up to this poster in a theater and had a close look, I suspect, you’d see quite a bit of distortion. In The Hobbit, they’ve added a bit of noise to mask the upresing and blend it in with the colors of the bucolic background scene, but I suspect the picture was a much higher res to begin with. Gatsby remains the clearest photo, and the crispness works well with the art deco concept. A designer could create any of these looks with a photo of like the one of Leo DiCaprio, but it would be hard to create a Gatsby-like effect with the photo of Richard Gere.

In the absence of a large format camera in a studio environment, to get as full a resolution as possible, here’s what I suggest, and I know this is a bit unorthodox, but it’s pretty straightforward. Set up a white sheet as a background, or if your subject has a lot of fly-away hair, you may want to try it with a green or blue screen. (I found a cheap one here.) This will allow the designer to take away the background to produce a cutout. This is really no big deal for a graphic designer, unless there is a ton of hair involved, in which case, be sure to try it with a number of different backgrounds. This isn’t a shampoo ad, so shaving off a little hair is forgivable in this arena.

First, take a normal full body shot in portrait orientation just so there is at least one shot of the entire scene you are trying to capture.

But this shot will not be the one that is used. Instead, break the photo up into several shots…the trick is not to hold the camera in portrait orientation but keep it in landscape while you do this…then later on your designer reassemble them into a unified whole.

Why do it this way? Last week, I showed you what you can expect to achieve with a 16.1 megapixel camera:

![]()

Doing it this way will give you the most resolution to work with…

You may need to do it a few times to insure consistency in terms of lighting etc., but with the magic of photoshop, this shouldn’t be much of an issue. You’d want to be careful not to break the shot in the middle of any complicated parts, such as the person’s eyes or mouth, for example.

Start with the person’s face…make sure not to cut off the top of the head (even though two of heads in the posters here are cropped)…

|

|

|

Then quickly lower the camera vertically and take another shot, so that the second overlaps just a bit, to get the upper part of the torso.

|

|

|

Make sure to take dozens of shots like these, so that you have enough photographs to mix and match, as sometimes the pictures can vary in terms of lighting, or your hand is not in the exact position, etc. If there is a prop involved, I would not have that in the shot, but just have them grip something similar and photoshop the item (like a sword) back in later. (Remember to also take pictures of the prop using this technique.)

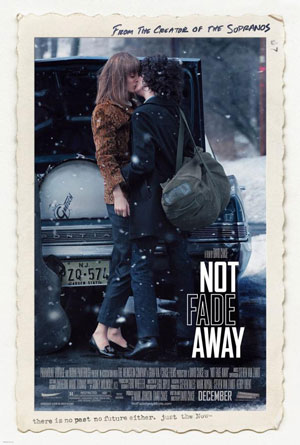

Perhaps you don’t want to feature just one character…after all, your film may not involve such a recognizable star as Richard or Leonardo. Let’s say you really want a particular shot of two of your main characters in some sort of pose. Like in the following film, Not Fade Away.

|

|

|

|

It is a bit counter-intuiative, but what I would do here is photograph the two characters in front of a solid background, not in front of the car. Then take a background photo (using the same technique here) of the car without the people. Then have your designer photoshop them together later. I would even go a step further and take a picture of the car without its background, and then take the trees as a separate photo. You never know how the composition will work best with your title treatment, or in different orientations (have a look at key art that is modified for a landscape orientation in iTunes trailer art…you’ll want to be able to move things around to create the look you want in the space that is allotted).

The point is that you are producing elements, not photos. Therefore, don’t just do this type of work for your actors/characters. Do it for your locations as well. You never know what background you may want to use, and the more shots you take, the more options you will have.

Of course, all this requires thinking ahead. But you will be glad you did.

Found this post informative? Check out David’s advice on Developing Key Art as your film enters the festival circuit.

David Averbach December 21st, 2012

Tags: film marketing, film posters, graphic design, key art, Photoshop, set photography, The Film Collaborative, unit publicist

Rethinking Your Key Art Game Plan, Part 1

Over the next several weeks, The Film Collaborative’s Creative Director, David Averbach, who has worked with dozens of TFC Clients and other filmmakers to help them create and refine their key art, will talk about ways you can avoid the problem of finding out all too late that you don’t actually have the proper materials to produce the key art you want to make.

Note: This Key Art series is intended for micro-budget filmmakers whose crew is not under a union contract. If your film’s crew is under an IATSE contract, you will need to abide by the rules regarding still photographers on set as forth by the union. We have been advised that there may be penalties involved by bringing an intern or PA in to shoot stills.

See Part II HERE

Takeaway: For narrative feature films, understanding the technical aspects of producing key art and thinking ahead to your key art while on your film set can save time, money and a heck of a lot of aggravation down the line.

If I had a nickel for every narrative feature filmmaker who has told me that they got a photographer, professional or otherwise, to come to their film set and shoot photos but in the end they didn’t show up or didn’t do a good job, or was only there for one day out of a sixteen day shoot, and therefore there was nothing to show for that effort in terms of producing images that could be incorporated into a poster, and therefore were only really left with the prospect of using frame grabs from their film, I’d be rich I could probably buy a Starbuck’s gift card that would last me a week or two.

I hope this series of posts can offer some helpful suggestions for you to avoid this situation for your next film.

First let me say that while I design movie posters, I don’t really have a background in filmmaking itself. If there is anything incorrect/inaccurate, generally unfeasible included here, or if you have anything you think I should add, please feel free to let me know. That said, it’s clear to me that in the heat of the film shoot, filmmakers often forget to think about or are so focused on the film shoot that they can’t get around to thinking about the art they might need to support a variety of possible marketing ideas and concepts, and are therefore down the road left with fewer choices and placed in an ultimately weaker position vis à vis possible options on how to market their film or sell it to a potential buyer without an expensive and inconvenient reshoot. (I’m working under the assumption that you are the type of filmmaker who has neither endless funds for a photo shoot 6 months after your shoot ends nor the energy to pull in yet another favor from some photographer you or one of your colleagues may have worked with in the past.)

There are two parts to tackling this problem. The first has to do with understanding resolution: what you have, what you need and how to bridge the two. The second has to do with beginning to think about your marketing strategy even before your film shoot, and preparing to build the raw materials you would need to execute any number of possible marketing directions.

So let’s talk about resolution first. (I’ll get to marketing strategy in Parts 2 and 3 of this series).

Knowing the resolution of your frame grabs

If you’re lucky enough to work with a 4K or 5K camera, such as a RED camera, meaning that the max output resolution is over 5000 pixels wide (5120×2560 on a RED) (which is about 6.5 times that of 1080p (1920×1080), those will produce beautiful film stills. So if you were to shoot your entire film in 5K, much of this next part won’t apply to you. In the real world, according to my DP friend, most people don’t and can’t afford the drive space and rig to do that in production. So if this is the case the highest output for a film grab might still be 1920×1080.

Now 1080p cameras that have a good quality and large sensor with a full chip (DP friend: preferrably not a 1/3 chip), will produce beautiful images…wonderfully clear, and of course you can blow them up to a certain extent without anyone noticing. But if you want your image to take up most of the width of your poster, you will have a resolution problem. The bottom line is, with 1080p output, if you want a theatrical poster using just a few main images, you won’t be able to really rely on frame grabs alone.

While frame grabs will probably work just fine to produce the key art for a DVD cover or a digital release, they are simply not going to cut it for a one sheet. And even while some films will never end up getting a proper theatrical release, all filmmakers tend to want a theatrical (sized) poster, especially if their film gets into a top-tier film festival.

Why won’t frame grabs work well? Well, Bill Clinton said it best: arithmetic.

Perhaps not every filmmaker knows how 1080p correlates to print resolution. As I state above, something that is shot in 1080p (16:9 aspect ratio) is 1920×1080 pixels in dimension. How many pixels will you need for a poster? Well, posters are usually 27×40 plus a ¼” bleed, and the minimum resolution is about 200 dpi (or dots per inch). That means that a poster needs to be at least 5500 pixels wide and that a frame grab would be up-res’d be almost a factor of 3 in order for it to stretch horizontally on a one sheet to even get up to 200dpi.

|

|

Until all cameras are 5K resolution and one can easily shoot their whole film this way, part of the collateral damage from the transition to digital is that this is yet one more thing that a filmmaker has to think about…in the days of 35mm, it was common practice to pick a frame of the film and scan it into a large still for use in a poster, but if the maximum output or effective maximum output from your camera is 1080p, you don’t have that luxury.

The end result will produce a blurry image at best and a pixelated image at worst. While this might be good for a background image, if you would like to use a close-up of someone’s face or a full body shot, this is just not going to look good.

Now that we’ve agreed that we need still photographs, what steps can you take to ensure that you will get something that you can use, both in terms of quality and content?

How to make sure you have images for key art—no matter what your budget

You are shooting with a great camera that can take great stills. But what if you can’t spare the time to use the camera you’re shooting on to also do stills?

On to Plan B. Hire a professional photographer, or at least someone with a really nice camera. In an ideal situation, you would get another 5D to take stills to complement the main motion picture camera. (Per my DP friend…Snug up to the lens…use Zeiss prime lenses for sharness or Canon L series lenses if going for more of a softer thing. If you can’t do that with your budget, use a monopod and critically check focus). This is great advice. If you have the budget for it.

But creating images for a poster is more than just producing nice photos. Shadowing the film shoot with a still camera often produces shots that are great for press stills, but may not be all that useful for a poster. Of course it depends on what kind of poster you will want to make. But in the end, it’s good to have a Plan C, and not in the sense that you need a third option because the first two didn’t work. I mean a concurrent Plan C.

This is it: Think of shots for key art as publicity shots, not as enlarged film stills. (And by “publicity shots,” I don’t mean for the actors, I mean publicity shots for the characters, so make sure they stay in character while you shoot them.) It’s fine to do what my DP friend says, but you need to do more. There’s lots of down time on a shoot. Actors are present and in costume and makeup. Move away from the action of the film. Use that hired photographer. Or use hire an intern with a good eye. Use that second 5K camera. Or get an inexpensive 16 megapixel camera. It doesn’t really matter. Just do it. Start outside around lunchtime, when the light is best. Find a white wall, or hang up a sheet outside somewhere. Think about what kind of poster you’d want to make. Develop half a dozen concepts (more on this in parts 2 & 3). Take it seriously. Start shooting.

What you should be creating here is this: Hi-res Scraps. You don’t know how you will use them, but at least you will have something.

Don’t have the budget for a second 5K camera? Fine. But we’ve gotten to a point where consumer cameras can actually produce extremely high quality and high resolution images. Last year, I bought this point-and-shoot camera on Amazon. It’s 16.1 megapixels. It lists right now at $150, but I think I bought it for $109 at one of those after Christmas sales. Every filmmaker has the budget for this much. You’ll be paying a lot more to correct this down the road if you feel this will put your budget over the edge.

See how much more you can get in terms of resolution when using a 16 megapixel camera as compared to a frame grab?

Is this a crappy camera? Compared to the ones you are using to film your shoot, absolutely. But graphic designers have their bag of tricks. Perhaps you’ve heard of Photoshop? We can make even images from these cameras look great. If the right shots are taken. So now there is no excuse to come back from a film shoot empty handed in terms of images for your key art… It is like buying key art insurance: you may not need to use it, but in a pinch you’ll be glad you have it.

Next week, in Part Two, I’ll give you some examples of a few concepts every film should have their “key art still person” shoot.

David Averbach December 12th, 2012

Tags: film marketing, film shoots, images, independent film, key art, One Sheets, Photograhers, posters, resolution, stills

Tips on producing Creative for your film

by David Averbach, Creative Director, The Film Collaborative

In the past two and a half years, The Film Collaborative has worked closely with hundreds of films. When it comes to Creative, such as key art, trailers, web sites, press kits and stills, we see a lot of small and not-so-small mistakes. As Creative Director of TFC, it’s my job to flag anything that could pose a problem, whether it’s on the film festival circuit, being presented to film buyers, or being prepared for digital distribution. In the coming months, I’m going to try and tackle many of these items one by one in depth. The first blog, if it indeed will fit in just one post, will focus on the technical, aesthetic and practical concerns involved with creating key art. In the meantime, I offer some teaser “tips”:

Trailers.

If your film is having a theatrical release, or even if it’s not, chances are that you will want it to be on iTunes one day, either in the iTunes store for sale/rent, or on iTunes Movie Trailers before your theatrical. Apple is very strict with their trailer specs: you’ll need to produce either a 1080p or 720p .mov file that is either uncompressed or outputted in ProRes HQ. They will not accept up-res’d or otherly compressed trailers. So make sure you leave room in your budget to produce such a file, because you may need your lab to do it for you. The good news is that a 2 minute trailer will generally fit on a data DVD, or a USB thumb drive, so you won’t need to buy a special hard drive to submit.

But there is one more catch: the trailer needs to basically be PG, or approved for appropriate audiences. Remember, trailers are not behind Apple’s pay wall. Apple will reject trailers that have expletives (even in subtitles) and nudity of any sort (including sex toys), and could reject a trailer for the same things that the might cause the MPAA to give the trailer anything but a green band if it were ever to be submitted for a rating, such as underage drinking, pot smoking, excessive violence, etc. So while cursing and nudity will definitely be rejected, for those of you who point to other trailers on iTunes with someone snorting cocaine in them, I would respond to you this way: why risk it? Are these things so essential to your trailer that you would want to have to pay your lab or editor to redo it, while at the same time postponing getting your trailer up? Remember, the majority of Apple’s trailers come pre-rated by the MPAA, who is known for being wildly inconsistent when it comes to their rating rationales. I have no reason to believe Apple is any different, and we know so little about their process that it doesn’t make sense to take chances. So if you want to create a racy trailer, that’s fine. Just also remember to create a squeaky clean version as well.

Press Kits.

Do you NEED a “designed” press kit? You know, the kind that has edge-to-edge bleed? The short answer: probably not, unless your film gets into a top-tier festival in Europe with a film market, such as Belinale/EFM or Cannes/Marché du film. Because if you don’t, it will be like showing up in a tweed jacket to a black tie wedding. Those Europeans have really nice press kits, with all of their fund and film foundation logos, so it’s best to play the game. And I believe that Berlinale asks for a certain number of printed copies to be sent to them in advance, and Cannes makes their press kits available for download right from the film detail page, so make sure you keep this in mind. Otherwise, there’s really no reason why your press kit can’t be a PDF of a Word document.

But that doesn’t mean it has to be boring. Why not use the same or similar fonts to the ones in your key art (you can even ask your designer to give you the fonts or your title treatment for this purpose) and create a really good-looking press kit yourself. But if you’re doing it in Word, don’t despair too much about how it looks when it is printed out. Very few people will do this, so don’t import hi-res photos into Word…it will only weigh your final document down. Use web-res photos (72 dpi sized down to no larger than 7.5″ wide) so that they can fit in your document and your file size can still remain relatively low. The last thing you want is a 12MB press kit…it’s just bad form. Keep it under 2MB, but absolutely no more than 4MB. Also keeping it in Word allows you to update it more regularly with new quotes or laurels. If you need samples, there are many examples of good-looking press kits on the TFC site.

Press Stills.

The stills you include in your press kit do not have to be the same set as the ones you make available to the Press and to film festivals? Why? Because in your press kit, they will be viewed as a group. In a review article or in a film festival catalog, there will be no more than a handful, and more often than not, they will only choose one, and you won’t get to choose which. Regrettably, many filmmakers send us photos to put up that are just plain dull; that have unreasonable copyright restrictions; or that are lo-res or poor quality. So, what questions should you be asking yourself when accessing photos? Here are a few: Does this photo represent the film well enough if that’s the only photo used? Will this photo make anyone want to see my film? Is this photo compelling? Engaging? Do you have a famous or recognizable star in your film? How will that photo look when placed next to six others in a festival catalog? Am I thinking about marketing when I chose this photo or am I thinking about art? If this were the only photo shown, does it make sense in conjunction with the synopsis I’m providing about my film?

Another recommendation: Embargo the main still you choose for your key art. Otherwise, your campaign can look unnecessarily narrow. If you look at the film carousel on TFC’s home page, you’ll see that each film has a different image as the main image in the carousel than from the image used most prominently in the poster.

And if you are using 1080p stills, which are only 1980 pixels wide (about 6.5 inches at 300dpi) do not crop your images, as festivals may need to use every inch to fit the design spec of their catalogs. Many festivals like having 16:9 images.

And for Pete’s sake, do not be stingy with your press stills. Make them available. Easily. Don’t require passwords or permission or complicated ways to download. You don’t have to offer every still this way, but you should have 5-10 that can go out into the world without complications.

Key Art.

Design your posters to be 2:3. Not the proportions of 8.5×11, or 11×17, or something else. This will give you the greatest flexibility as you move forward with marketing.

So, if we’re talking web-res, like for IMDB of if you’re submitting for VOD, 1200×1800 is a great size to give them, although Apple requires 1666×2500. They don’t display the art this big, but they appreciate being sent these sizes, not tiny thumbnails.

But even before you are submitting, have your designer output samples in a variety of sizes, like 600×900, 300×450, 200×300 and 150×225 (all multiples of 2:3), or resize them yourself in Photoshop or Apple’s Preview app. Why? Because you need to access your art and see how it’s going to look in a variety of sizes. What will it look like when it appears in the iTunes store or Netflix or Flixter next to an array of other titles? What happens when you see it a little bigger, like on a detail page? Can you make out the title and the main image? This is probably the most important question you need to ask regarding the value of your key art, and you need to do it in the size it will be when it’s finished.

How about printed one-sheets? Printed posters in the U.S. are either 27×39 or 27×40. It’s close to 2:3 but not exactly. And you may need up to a .25” bleed on all sides. So tell your designers to design to 27.5 x 41.25. That is 2:3, so you can then take your huge poster file and resize it down to your webres sizes. Make sure to leave plenty of room on all sides, so you’ll be able to crop it to the size your printer can print, and also you won’t run into the risk of having the edges of your poster blocked by a marquee and making your poster feel unnecessarily cramped.

Website.

Do you need a website? Yes. Will people think less of your film if you throw up a generic-looking WordPress site? Yes. Stay away from flash sites…they are pretty but costlier and harder to maintain and not viewable on many, many mobile devices. The best sites integrate Facebook, have a trailer, provide a list of where the film is screening, and have a place where film festivals/industry can go to get what they need. This is the minimum. I believe that it’s better for your site to inspire confidence by good aesthetics and do less than for your site to do everything under the sun and look like heck. Because there’s always your Facebook fan page as well. I’m certain that our Director of Social Network Marketing has a lot to say on this subject, so maybe in the future, you’ll see a joint blog post where the two of us can hash out the relationship between website form and function.

I hope these tips were helpful. And TFC members, keep in mind that if you need advice about any of your creative, you can request that some of the hours you receive for distribution analysis with your TFC membership go toward advice about your Creative.

David Averbach August 1st, 2012