The Audacity of Hope: A Window into the Minds of Filmmakers at Independent Film Week

Next week (September 15 – 19) marks IFP’s annual “Independent FIlm Week” in NYC, herein dozens of fresh-faced and “emerging” filmmakers will once again pitch their shiny new projects in various states of development to jaded Industry executives who believe they’ve seen and heard it all.

Most of you reading this already know that pitching a film in development can be difficult, frustrating work…often because the passion and clarity of your filmmaking vision is often countered by the cloudy cynicism of those who are first hearing about your project. After all, we all know that for every IFP Week success story (and there are many including Benh Zeitlin’s Beasts of the Southern Wild, Courtney Hunt’s Frozen River, Dee Rees’ Pariah, Lauren Greenfield’s The Queen of Versailles, Stacie Passon’s Concussion etc…), there are many, many more films in development that either never get made or never find their way into significant distribution or, god forbid, profit mode.

So what keeps filmmaker’s coming back year after year to events like this? Well, the simple answer is “hope” of course….hope, belief, a passion for storytelling, the conviction that a good story can change the world, and the pure excitement of the possibilities of the unknown.

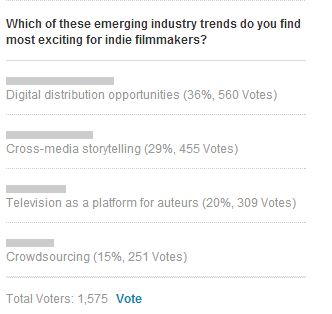

Which is why I found a recent poll hosted on IFP’s Independent Film Week website [right sidebar of the page] so interesting and so telling….in part because the result of the poll runs so counter to my own feelings on the state of independent film distribution.

On its site, IFP asks the following question:

Before you view results so far, answer the question….Which excites YOU the most? Now go vote and see what everyone else said.

** SPOILER ALERT — Do Not Read Forward Until You’ve Actually Voted**

What I find so curious about this is in my role as a independent film distribution educator at The Film Collaborative, I would have voted exactly the other way.

I suspect that a key factor in IFP Filmmakers voting differently than I has something to do with a factor I identified earlier, which I called “the pure excitement of the possibilities of the unknown.” I’m guessing most filmmakers called the thing most “exciting” that they knew the least about. After all 1) “Crowdsourcing” seems familiar to most right now, and therefore almost routine to today’s filmmakers….no matter how amazing the results often are. 2) “Television As a Platform for Auteurs” is also as familiar as clicking on the HBO GO App….even despite the fact that truly independent voices like Lena Dunham have used the platform to become household names. 3) Cross Media Story Telling remains a huge mystery for most filmmakers outside the genre sci-fi and horror realms….especially for independent narrative filmmakers making art house character-driven films. It should be noted that most documentary filmmakers understand it at least a little better. And 4) Digital Distribution Opportunities…of course this is the big one. The Wild West. The place where anything and everything seems possible…even if the evidence proclaiming its success for independents STILL isn’t in, even this many years after we’ve started talking about it.

But still we hope.

From our POV at The Film Collaborative, we see a lot of sales reports of exactly how well our truly independent films are performing on digital platforms….and for the most part I can tell you the results aren’t exactly exciting. Most upsetting is the feeling (and the data to back it) that major digital distribution platforms like Cable VOD, Netflix, iTunes etc are actually increasing the long-tail for STUDIO films, and leaving even less room than before for unknown independents. Yes, of course there are exceptions — for example our TFC member Jonathan Lisecki’s Gayby soared to the top of iTunes during Gay Pride week in June, hitting #1 on iTunes’ indie charts, #3 on their comedy charts, and #5 overall—above such movie-star-studded studio releases as Silver Linings Playbook and Django Unchained. But we all know the saying that the exception can prove the rule.

Yes, more independent film than ever is available on digital platforms, but the marketing conundrums posed by the glut of available content is often making it even harder than ever to get noticed and turn a profit. While Gayby benefited from some clever Pride Week-themed promotions that a major player like iTunes can engineer, this is not easily replicated by individual filmmakers.

For further discussion of the state of independent digital distribution, I queried my colleague Orly Ravid, TFC’s in house guru of the digital distro space. Here’s how she put it:

“I think the word ‘exciting’ is dangerous if filmmakers do not realize that platforms do not sell films, filmmakers / films do.

What *is* exciting is the *access*.

The flip side of that, however, is the decline in inflation of value that happened as a result of middle men competing for films and not knowing for sure how they would perform.

What I mean by that is, what once drove bigger / more deals in the past, is much less present today. I’m leaving theatrical out of this discussion because the point is to compare ‘home entertainment.’

In the past, a distributor would predict what the video stores would buy. Video stores bought, in advance often, based on what they thought would sell and rent well. Sure there were returns but, in general, there was a lot of business done that was based on expectation, not necessarily reality. Money flowed between middle men and distributors and stores etc… and down to the sellers of films. Now, the EXCITING trend is that anyone can distribute one’s film digitally and access a worldwide audience. There are flat fee and low commission services to access key mainstream platforms and also great developing DIY services.

The problem is, that since anyone can do this, so many do it. An abundance of choice and less marketing real estate to compel consumption. Additionally, there is so much less of money changing hands because of anticipation or expectation. Your film either performs on the platforms or on your site or Facebook page, or it does not. Apple does not pay up front. Netflix pays a fee sort of like TV stations do, but only based on solid information regarding demand. And Cable VOD is as marquee-driven and not thriving for the small film as ever.

The increasing need to actually prove your concept is going to put pressure on whomever is willing to take on the marketing. And if no one is, most films under the impact of no marketing will, most likely, make almost no impact. So it’s exciting but deceptive. The developments in digital distribution have given more power to filmmakers not to be at the mercy of gatekeepers. However, even if you can get into key digital stores, you will only reach as many people and make as much money as you have marketed for or authentically connected to.”

Now, don’t we all feel excited? Well maybe that’s not exactly the word….but I would still say “hopeful.”

To further lighten the mood, I’d like to add a word or two about my choice for the emerging trend I find most exciting — and that is crowdsourcing. This term is meant to encompass all activities that include the crowd–crowdfunding, soliciting help from the crowd in regard to time or talent in order to make work, or distributing with the crowd’s help. Primarily, I am going to discuss it in terms of raising money.

Call me old-fashioned, but I still remember the day (like a couple of years ago) when raising the money to make a film or distribute it was by far the hardest part of the equation. If filmmakers work within ultra-realistic budget parameters, crowd-sourcing can and usually does take a huge role in lessening the financial burdens these days. The fact is, with an excellently conceived, planned and executed crowdsourcing campaign, the money is now there for the taking…as long as the filmmaker’s vision is strong enough. No longer is the cloudy cynicism of Industry gatekeepers the key factor in raising money….or even the maximum limit on your credit cards.

I’m not implying that crowdsourcing makes it easy to raise the money….to do it right is a whole job unto itself, and much hard work is involved. But these factors are within a filmmaker’s own control, and by setting realistic goals and working hard towards them, the desired result is achieved with a startling success rate. And it makes the whole money-raising part seem a lot less like gambling than it used to….and you usually don’t have to pay that money back.

To me, that is nothing short of miraculous. And the fact that it is democratic / populist in philosophical nature, and tends to favor films with a strong social message truly thrills me. Less thrilling is the trend towards celebrities crowdsourcing for their pet projects (not going to name names here), but I don’t subscribe to a zero-sum market theory here which will leave the rest of us fighting over the crumbs….so if well-known filmmakers need to use their “brand” to create the films they are most passionate about…I won’t bash them for it.

In fact, there is something about this “brand-oriented” approach to crowdsourcing that may be the MOST instructive “emerging trend” that today’s IFP filmmakers should be paying attention to…as a way to possibly tie digital distribution possibilities directly to the the lessons of crowdsourcing. The problem with digital distribution is the “tree-falls-in-the-forest” phenomenon….i.e. you can put a film on a digital platform, but no-one will know it exists. But crowdsourcing uses the exact opposite principal….it creates FANS of your work who are so moved by your work that they want to give you MONEY.

So, what if you could bring your crowdsourcing community all the way through to digital distribution, where they can be the first audience for your film when it is released? This end-to-end digital solution is really bursting with opportunity…although I’ll admit right here that the work involved is daunting, especially for a filmmaker who just wants to make films.

As a result, a host of new services and platforms are emerging to explore this trend, for example Chill. The idea behind this platform (and others) is promising in that it encourages a “social window” to find and engage your audience before your traditional digital window. Chill can service just the social window, or you can choose also to have them service the traditional digital window. Crowdfunding integration is also built in, which offers you a way to service your obligations to your Kickstarter or Indiegogo backers. They also launched “Insider Access” recently, which helps bridge the window between the end of the Kickstarter campaign and the release.

Perhaps it is not surprising therefore, that in fact, the most intriguing of all would be a way to make all of the “emerging trends” work together to create a new integrated whole. I can’t picture what that looks like just yet…and I guess that is what makes it all part of the “excitement of the possibilities of the unknown.”

Jeffrey Winter will be attending IFP Week as a panelist and participant in the Meet the Decision Makers Artists Services sessions.

Jeffrey Winter September 12th, 2013

Posted In: crowdfunding, Digital Distribution, DIY, Film Festivals, iTunes, Long Tail & Glut of Content, Marketing

Tags: cable VOD, cross media storytelling, crowdfunding, Crowdsourcing, digital film distribution, Gayby, hope, IFP, Independent Film Week, iTunes, Jonathan Lisecki, Netflix, Orly Ravid, The Film Collaborative

Dorothy, we ARE in Kansas. Forget about Oz

I feel like a broken record. There is nothing I am writing here that I have not said and written many times before. Still. After all that has gone on in distribution. The willful blindness of filmmakers believing in the Oz fairytale of going to a festival, A-list or otherwise, without putting in the work of building an audience around their film, with the hope of a big sale. It is an unsupported hope of a deal that does not merit the delay of doing the work to connect with fans. They may go with a very skilled sales agent, and yet the sale that is made, if any, is one that the filmmaker could have done directly without giving up rights to their film and possibly even have done without signing such agreements because the offer was too low.

To be honest, we’re big fans of doing distribution deals in tandem with direct distribution by the filmmaker, so it’s not doing the deal that bothers me, especially not if it’s a good offer and additional work is going to be performed by the distribution company in service of the film. What is a big deal is the lost marketing opportunity that comes from waiting for this mythical deal for too long. The failure to capitalize on all the buzz and press that happens at a festival which gives a small film the launch it needs to resonate with fans and convert them to purchasers. Too many times, the filmmaker is told (by the industry) to hold out for an offer that never comes. The real indie film landscape looks much more like Kansas after the tornado, rather than the Emerald City. There is no yellow brick road that leads everyone to “the wizard” with the money. We are all building our own road.

This myth of waiting for the big offer is perpetuated in the press and by the industry. A few films get lucky and go to Sundance, SXSW, Cannes etc., and, for one reason or another, a distributor pays a lot of money to buy them. Why does that happen? Sometimes “festival fever” is high among the buyers to compete with each other and pressure to make higher bids than they should. Sometimes it’s a new distribution company trying to prove itself by outbidding more established players. Sometimes it’s personal like wanting to produce the director’s next film. Sometimes a film warrants paying good money for it, so sure is the buyer that they have an audience winner, or film that will be critically acclaimed or a major award winner. In any case, that happens very few times a year to be sure. MOST deals these days (relative to the number of films made and even shown at festivals) are not like that.

Generally, the money offered upfront does not even make the investors whole. The money ultimately remitted to the investors does not yield a profit most of the time for films without big name cast or at the top of their genre category. It seems to me filmmakers focus on the exceptions, the success stories, and ignore the rest of the data.

I was asked via our Facebook page to estimate what the budget for LGBT films should be because it is the kind of films we have A LOT of experience handling. Based on all our work in that space, I can say if you make your film for more than $150,000, you are taking a big risk of remaining in the red. It may still be a risk that at that price, but if it has decent production value, a very good story and pops at the right festivals, you can do deals and DIY and monetize all revenue fronts to make that budget back… maybe even as much as $250,000. But again, that is the exception, not the rule because there are a lot of Ifs in that last sentence. Often the revenue outcome is less in fact. Time to get to know the real story, not the ones being perpetuated to show financial success as the norm.

What I am urging now is to be MINDFUL OF TIME and LOST OPPORTUNITY and not just search for the yellow brick road expecting the wizard to make magic happen for your film. There’s just not that much magic left. While there still is some talent “getting discovered” (and to be honest this is often happening first in lab programs, not at prestigious festivals), big deals being done, careers being made (this happens annually at Sundance and even SXSW), you need to be honest with yourself about where your work lies in that realm of possibility based on the elements you have in place right now. At least have a back up plan put into action that sets up the film for capitalizing on the audience you have been building and continue to build at first shot out in public. So many films lose that chance and it will never come again for them. The task is too arduous to start all over again after the glare of the initial media and attention dies down.

This would not be a Film Collaborative post if I did not share some data with you about what is happening with films that are building their own roads to “Oz.” More specifics will be provided in the next post because we are waiting for it to come in, but for now let’s take a look at one avenue that filmmakers are still questioning, selling streams from their own website.

At Sheffield DocFest, Sheri Candler talked to DIY platform DISTRIFY with whom TFC works as does Wolfe Video, for example. Filmmakers should think about using services such as Distrify for both the purpose of selling off one’s site(s) and/or if one’s conventional distributor partners with the service (in which case hopefully the filmmaker has an affiliate relationship and receives a healthy percentage from any sales they make from their own website). Distrify cautions that for the most part filmmakers think they can put a film on a platform and wait for the cash to roll in. “We have probably 3,000 films on the service now and I’d reckon that nearly half have never sold at all- because they’ve never told anyone that they are there!,” said Peter Gerard, co founder of Distrify. For stronger films that appeal to an identifiable niche, if filmmakers make the effort to audience-build and market to that audience, Gerard says those films sell a few thousand units… For the UK, for example, these numbers are compatible with conventional DVD sales and the market as a whole. A market that is a fraction of the one in the US.

Gerard also says “Mailing lists are still the most effective way to sell – our data shows that a well-written and well-targeted mail-shot converts at a much higher ratio than Facebook or Twitter posts. Gathering Facebook likes or followers is maybe somewhat helpful, but is primarily a vanity exercise. The top-performing films focus on direct links with people via emails, blogs, and real-life events.” All this stuff TFC’s been shouting about for years (build an email list, build relationships with fans etc) can be verified in the data! We want to add that building your Facebook and Twitter accounts can demonstrate appeal to distributors seeking to assess a title to buy so we still recommend it if you are looking to make a sale. And, in the US, it may help drive awareness for the sake of building demand on commercial platforms such as Netflix.

Gerard goes on to note: “I don’t think it helps most people to say this movie made $40k or this one made $20k. I think that can be misleading because I firmly believe there is no such thing as an “average low budget film” nor a “usual amount of marketing”. We work with a wide gamut of films, and success is measured very differently depending on a range of factors. We’ve had some filmmakers earning a few hundred bucks a week and re-investing that immediately into low-budget production of serial dramas or new films. We’ve paid Nigerian filmmakers 4-figure sums recently. A first-time filmmaker earned $10k in a few weeks on a super-niche short documentary and re-invested the profits into both charity donations and DVD production for selling on the ground via real-life social networks. All of these are considered big successes for the people involved.” One of TFC’s filmmakers will be a case study down the line as the film has been a standout performer on Distrify, but that is because of the filmmakers’ efforts, her long-standing brand, and also efforts of her distribution partner.

In another future post, we will be highlighting a filmmaker who has taken a completely different path to releasing his work. Rather than living in NYC or LA, he lives in Memphis, TN, a way cheaper place to live and to film in. He has built a respectable following of his own because he’s tapped into a specific niche (not LGBT) audience that is large enough to support the films he is making.

He seems happy and his sustainable filmmaking career is a refreshing reminder that it is possible to turn away from conventional wisdom on how things in the film business work. He’s is building his own road and it might never lead to Oz, but he is the wizard pulling the levers for his work in the “post tornado Kansas” that is today’s indie film landscape.

Orly Ravid July 18th, 2013

Posted In: Distribution, DIY, Film Festivals, Marketing

Tags: direct distribution, Distrify, Film Festivals, filmmaker fairytale, independent film distribution, Orly Ravid, Peter Gerard

Finding distribution for the NC-17 equivalent film FOURPLAY

Today we have a guest post from filmmaker/educator Kyle Henry

Someone told me years ago that sex sells. Unfortunately, when I started making my anthology of short sex tales feature FOURPLAY four years ago, I thought that if a little sex sells then A LOT of sex would REALLY sell. Although the director side of my brain was motivated by a lot of high-minded reasons (e.g. showing sex as a positive force; providing understanding for characters participating in “deviant” sex acts; rescuing cinematic sex from titillation for catharsis), the producer side of my brain thought that by providing a product that would fill a need (e.g. an adult explicit film about sex that isn’t porn) somehow axiomatically would pull off a hat trick of making a profit AND getting away with subversive cultural critique. Well, we’ll see about that later part because just finding distribution has been a long and winding road depending almost exclusively on our persistence and ingenuity. Both were needed to prove the film’s potential to a very risk averse market for narrative NC-17 equivalent films dealing with sex even in our libertine digital age.

We didn’t start out five years ago making FOURPLAY thinking this would be such a struggle. I’ve always been interested and motivated to tell stories that challenge dominant frameworks of understanding. It’s the old activist in me still rearing its authority challenging head, but I thought that our four tales, which were mostly comedies, would hit that sweet spot of entertaining subversion. First word of warning: be wary of thinking your milieu of friends is representative of the general public as a whole.

Turns out, I live in a bit of a freak bubble. Now, there’s nothing wrong in making your work for yourself and your friends, just try to be aware how large that base is and don’t fool yourself that everyone is going to love your gang-bang heretical bathroom farce (e.g. our Tampa segment) or your cross-dressing sex-worker meets quadriplegic man for spiritual union melodrama (e.g. our San Francisco segment). I was very lucky to find grant money from the Austin Film Society, the wickedly funny producer Jason Wehling who likes doing things on the very cheap, and support from patron angel executive producers Michael Stipe and Jim McKay, who lent monetary and name support to the project via their C-Hundred Film Corp so we didn’t come off as complete yahoo wackos. Second word of warning: if you’re going to make a subversive work that will challenge the body politic and marketplace, make it on the cheap! All of these factors, plus the extreme desire to never again dip into my credit cards to make films, lead us to keep the budget under six figures, which gave us the ability to be not too desperate and come up with alternate strategies when hit with the brick wall of distributors saying “no thank you.”

Well, we were a little desperate in the beginning or perhaps a little too “creative” in our distribution thinking. There is a distributor out there who will go unnamed whose major selling point to filmmakers is a transparent “back-end” for their on-line sales of both DVDs and streaming content. That means when someone buys your content, you instantly see the sale by logging into their producer portal. We had the “clever” idea of releasing three of the four shorts that comprise FOURPLAY at both festivals and online as we finished them, with the idea being we’d make a little scratch along the way of production.

Production of the four shorts was strung out over the course of two years, basically whenever I had breaks from both teaching and editing, which I do also concurrent to directing to make a living because I don’t have a trust fund. Third word of warning: if you want to make subversive independent cinema in America have other skills that pay the bills or have a trust fund. No one that I know who is making this kind of work (and I know A LOT of filmmakers) is making a living exclusively from their directing projects.

Getting back to this unnamed distributor. After we finished the first short, our San Francisco sex-worker segment which premiered at Outfest in 2010, we signed up with this distributor and started streaming the segment. It was gratifying to see the hundreds of sales rack up on their “open architecture” site, but it was frustrating and irritating beyond belief never to get a check from them. One quarter, then two quarters went by with no payment. Emails and letters were sent, never to be replied to on their part. Finally, I had to get a lawyer friend involved, who luckily I met after making Room in 2005 and would only charge me poverty charity rates, but I still sunk around $500 that I didn’t have into legally harassing said distributor to get first payment and then rights back to the project when they never paid up and were flagrantly in breach of contract. Fourth word to the wise: have an entertainment lawyer friend!

Turns out, this distributor had not paid a lot of people. One filmmaker friend of mine literally had to march into their NYC offices and camp out in their lobby, refusing to leave until he got a check from them, or so the story goes. Fifth word to the wise word: always ask your filmmaker/producer friends for the straight dirt on a potential distributor before signing a deal. I wish we had done more research before falling for their “because you see it on our site you’ll definitely get paid” baloney. Digital transparency doesn’t equal material cash.

The second segment, our gang-bang farce in Tampa, hit the festival jackpot of premiering both at Cannes’ Directors’ Fortnight 2011 and Sundance 2012. This raised the project’s artistic street cred, but … as our most explicit, outrageous and heretical segment, I think it scared off any distributor that might have been attracted by those festival laurels. It has a lot of cock on display, fake prosthetic cock, but still enough showing to scare both the horses and the largest and most profitable online distributor of streaming content, who will also go unnamed. Luckily we have a friend inside said organization who took a gander at the film and told us straight out “too much cock” so we didn’t waste time or money trying to alter the work or submit via an aggregator.

The final anthology feature with all four segments premiered at Frameline last summer, and again I threw a final curve ball to another potential type of distributor, those who specialize in LGBT content, by including a “straight sex” and a lesbian bestiality segment. Granted, in the “straight” segment a couple conceives in a gay video porno arcade, and our bestial segment is more about sublimation than doing the nasty with doggie, but it didn’t help anyone narrow down who would be interested in our film. It’s seems we had something to both interest … but also offend everyone. So, another string of no thank you’s from everyone, and I mean everyone, as we played the festival circuit throughout the summer and fall in 2012.

By early fall, I knew if anyone was going to want to see the film, we had to find a cheap way of getting some reviews and attention to back up our assertion that the work would gain enough publicity and digital markers to direct traffic to at least our own DIY efforts (e.g. making a self-produced DVD available off our site, streaming via Distrify, et al) … but just maybe one of those no’s would become a yes. Going back to my activist days, I hired two former student interns to put together a database of every independent cinema in North America that had screened NC-17 content in the last few years. We then sent out e-mails to around 300 theaters, followed up with phone calls, mailed press-kits/dvds to 100 theaters who expressed interest, and persistently bugged for over five months a narrow set who didn’t say no out-right to end up with the twelve who screened the film either as full week (e.g. Austin’s Alamo Drafthouse, Denver’s Sie Film Center), multi-night (e.g. Portland’s Clinton, Seattle’s NW Film Forum, Chicago’s Siskel) or one-off runs (e.g. LA’s Egyptian, NYC’s LGBT Center, Longbeach’s Art Cinema). Since all prints were digital, I either delivered on Blu-Ray, DCP or QT file, all generously discounted by a very cheap institutional FedEx rate, one of the perks of academia. Finally, my partner Carlos Treviño is not only the brilliant writer of three of the four shorts, but is also a talented graphic designer who designed not only our DVD case but also our web-site, based on a great (and highly discounted) poster designed by filmmaker/designer Yen Tan. I’m also an editor by trade, so I designed the DVD. Sixth word: directors, have some skills and partner up with people with skills beyond directing! Doing everything in-house is A LOT cheaper than hiring a bunch of free-lancers. In all, we spent around $15K to do our limited theatrical and first batch of 1,000 DVDs, which also includes the cost of me traveling for Q&A’s to all twelve venues.

One of the biggest line-items was hiring a real publicist for theatrical, Matt Johnstone, who also publicized the festival launch of both the San Francisco segment at Outfest, the Tampa segment at Sundance and the final feature at both Frameline and Outfest in 2012. Matt was with the project for almost three years from that first festival launch and became quite invested in selling the project. We wisely chose Austin, my former hometown, as the site to launch our theatrical tour. Seventh word: build from your base, which doesn’t have to be NYC or LA. I got the idea from the way Rick Linklater built distribution for both Slacker and many years later Bernie. By opening in Austin, we got both huge feature articles in both the daily and weekly, but also great reviews (not a guarantee, but I was thankful) and additional TV and radio interviews. It was about as saturated of media coverage as we were ever going to get and it paid off not only with a modest box-office to help immediately repay some of the debt I had incurred, but also we instantly showed up on Rotten Tomatoes with two boffo reviews!

This is where persistence comes into play. Everyone told us that doing theatrical was stupid for a no-budget sex-film, but in this day and age you still need reviews and digital ink from reputable sources to get anyone to want to see your film on whatever platform you end up on. I couldn’t blow a lot of money on it though. Filmmakers routinely spend $30- $50K hiring a booker, paying to four-wall and hiring a publicist for LA and NYC markets only for the privilege of reviews. I did this in minor-markets for a third to a fifth of that cost to accumulate markers from decent sources, although not the NY Times, but there’s no guarantee the Times would’ve liked the film anyway. These great reviews attracted the attention of a person in the DVD division of TLA Releasing, one of those distributors who said no last year, but because the film was proving itself in the market-place of ideas, now was interested in re-selling our DVD. Because it cost them nothing to manufacture, and no advertising on their part, we were able to negotiate a decent straight up purchase of a sum of DVDs that instantly repaid me what I spent to manufacture the first 1000. Up on their site, pre-sales were available before the end of our theatrical, so press attention continued to drive up sales, allowing us to sell them another batch of DVDs that now has put us into profit on the DVD before its official release date. That certainly wasn’t the case for my first feature ROOM’s DVD deal. Finally, I think it just made sense for TLA, one of the major distributors of LGBT content, that the film was getting spotlighted for it’s LGBT boundary pushing creds and whatever negatives there were with varied content wouldn’t undermine the major critical take-aways they could sell.

Finally, our publicist came up with the great idea of selling TLA on VOD rights also, since we were doing a press-release for the DVD launch and all traffic could be directed to one site. Again, this was a win-win situation for the distributor, as it required almost no work on their part, guaranteed sales, and provided us with the legitimacy of having a one-stop-shop on a press-release so sales could be maximized through focusing on one link in reviews instead of confusing consumers by sending them to multiple platforms. The legitimization we earned through good press during our limited theatrical lead to confidence being built that there actually was an audience for our weirdo film and gave everyone publicity ammunition to prove this assertion. No one was going to make this happen for us, we had to do this ourselves, and that’s my Final Word of Advice: DIY is here to stay for independent filmmakers.

When I first got into Sundance and Cannes in 2005 with my feature Room, I thought I had “arrived” and that upon being purchased by an international sales agency the film would sell itself. Although Celluloid Dreams poured a decent amount of money into sales, publicity and advertising to sell the film to various markets, the experience taught me that your job as a filmmaker is to CONSTANTLY sell your film once its made, no matter who picks it up or in what form for distribution. Distribution and sales companies are like roulette tables. They put down many chips on the table and if the ball lands on a number, all the other numbers lose, and the company will naturally follow a winner to the exclusion of all the “losers.” You want your film to win by being seen and, ideally, also make back a bit of you and your investor’s money. By keeping my production costs low, but producing my work with a combination of grants, crowd-source funding, and small investments from what I’d deem as “patron” investors who are far more interested in whatever “cause” my film is promoting than in returning a profit, I had the flexibility to be persistent.

That persistence was also fueled on the cheap, with: dogged interns who gained valuable insight into the distribution process while not breaking my bank; through a long six-month booking process that allowed said interns to work for cheap because it was only part time while they worked their real jobs to survive; through my academia network, which built relationships with presenting non-profits in every market to build audience and outreach for discussion on issues surrounding sexuality just like a doc filmmaker would organize; and through building long terms relationships with professionals who are also friends, like our publicist, our producers and my lawyer, who stick with me and the film on bargain rates because in some way they support me and the work as a team.

This has been the real hat trick, not only finding distribution and some sort of on-line home for an NC-17 equivalent film, but continuing to build long term relationships with other creatives who might be down for yet another subversive adventure when the next film inspiration strikes.

FOURPLAY is now available on DVD/VOD streaming from TLA here http://www.tlavideo.com/gay-fourplay/p-350944-2

FOURPLAY official web-site http://www.fourplayfilm.com/

Kyle Henry is a filmmaker, editor and educator. His narrative feature Room debuted at Sundance and Cannes’ Directors’ Fortnight in 2005. He is also the editor of the Emmy Award winning 2011 documentary Where Soldiers Come From, as well as this year’s SXSW premier doc Before You Know It. He currently teaches film production at Northwestern University.

Sheri Candler May 15th, 2013

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, DIY, Film Festivals, Marketing, Publicity, Theatrical

Tags: Alamo Drafthouse, Art Cinema, Austin Film Society, C-Hundred Film Corp, Cannes, Carlos Trevino, Celluloid Dreams, Clinton, FOURPLAY, Frameline, Jason Wehling, Jim McKay, Kyle Henry, LGBT, LGBT Center, Matt Johnstone, Michael Stip, NC 17, NW Film Forum, Outfest, Room, sex positive, short films, Sie Film Center, Siskel Film Center, Sundance, TLA Releasing, Yen Tan

Considerations BEFORE signing over your film’s home video rights

Although DVD distribution revenue has by all accounts declined significantly since the start of home video and the development of the format, most film distributors still distribute DVDs. Sales are down, but there are profits to be had for more commercial or popular fare that is strongly supported with marketing spend, whether studio, indie, or niche.

We always advise filmmakers to conduct Direct Distribution of DVDs to their audience even when we or someone else is handling licensing deals for them. Often though, if a distributor takes on Home Video (i.e. DVD), the expenses associated with the release and the diminishing revenues are the explanation for why digital rights must be licensed to the distributor along with the rights to release the film on traditional physical formats. Digital rights, at least many of them, rightly belong in the home video category,but here’s the rub. While the distributor has more money and more connections and ability to get a DVD into retail stores, they likely take a bigger commission on digital platform sales than an aggregator who is paid a flat fee or a smaller percentage. Of course, even direct digital distribution (streaming from your own site) requires some service or other that takes a fee. It’s just usually less costly than a conventional distributor’s fee. Back to the rub.

So a well heeled distributor gets a big retailer to order your DVDs when you could not have achieved that on your own and probably more money is spent marketing it than you ever could afford to spend. But note that’s also more money to be recouped before you see a return. The DVDs that don’t sell come back. And what comes back gets credited. It should be noted, many conventional distributors take their sales fee off of initial sales, regardless of returns.

So the distributor has the muscle to move the units to a retailer, but not enough muscle to get the public to buy them. They did their best, and even risked their expenses and time and staff energy. But the units come back just the same. Their sales fee is calculated off the top and the net left over for the filmmaker can be paltry. You may or may not be worse off than having done all the distribution yourself.

It is something to think about before you push for traditional distribution where there is not a big enough advance, or none, to recoup your initial investment in the project and you might have been better going it alone, still holding the rights over your film. These things are indeed a calculation of your time and money vs the distributor’s. At least check your contract for language that allows the distributor to keep the sales fee even for the sum of sales attributed to units ultimately returned and refunded. Perhaps compare potential results. Insist on a direct distribution clause so at least you have the chance to make the direct sales to the fan base you have worked so hard to build on your own. Or get clear about what your distributor can do for you that you cannot do for yourself, if anything, and what that is worth to you. Then make sure the contract comports accordingly.

Orly Ravid May 2nd, 2013

Posted In: Distribution, DIY, Marketing, Retailers

Tags: direct distribution, DVD distribution, home video sales, independent film distribution, Orly Ravid, The Film Collaborative

Indie Game: a distribution case study

This article first appeared on the Sundance Artist Services blog on August 13, 2012

written by Bryan Glick with assistance from Sheri Candler and Orly Ravid

Indie Game: The Movie has quickly developed a name not just as a must-see documentary but also as a film pioneer in the world of distribution. Recently, I had a Skype chat with Co-directors James Swirsky and Lisanne Pajot . The documentary darlings talked about their indie film and its truly indie journey to audiences.

Swirsky and Pajot did corporate commercial work together for five years and that eventually blossomed into doing their first feature. “We thought it would take one year, but it ended up taking two. I can’t imagine working another way, we have a wonderful overlapping and complimentary skill set, ” said Pajot. “We both edited this film, we both shot this film. It creates this really fluid organic way of working. It’s kind of the result of 5 or 6 years of working together. I don’t think you could get a two person team doing an independent film working like we did on day one. It’s stressful at times but the benefits are absolutely fantastic, ” said Swirsky.

Swirsky and Pajot did corporate commercial work together for five years and that eventually blossomed into doing their first feature. “We thought it would take one year, but it ended up taking two. I can’t imagine working another way, we have a wonderful overlapping and complimentary skill set, ” said Pajot. “We both edited this film, we both shot this film. It creates this really fluid organic way of working. It’s kind of the result of 5 or 6 years of working together. I don’t think you could get a two person team doing an independent film working like we did on day one. It’s stressful at times but the benefits are absolutely fantastic, ” said Swirsky.

According to Swirsky, Kickstarter covered 40% of the budget. “We used it to ‘kickstart’, we asked for $15000 on our first campaign which we knew would not make the film, but it really got things going. The rest of the budget was us, personal savings.” The team used Kickstarter twice; the first in 2010 asking for $15,000 and ended up with $23,341 with 297 backers. On the second campaign in 2011, they asked for $35,000 and raised $71,335 with 1,559 backers.

The hard work, dedication, and talent paid off. Indie Game: The Movie was selected to premiere in the World Documentary Competition section at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival winning Pajot and Swirsky the World Cinema Documentary Film Editing Award . “[Sundance] speaks to the independent spirit. It’s kind of the best fit, the dream fit for the film. Just being a filmmaker you want to premiere your film at Sundance. That’s where you hear about your heroes,” noted Swirsky. “Never before in our entire careers have we felt so incredibly supported…They know how to treat you right and not just logistics, it’s more ‘we want to help you with this project and help you next time.’ It was overwhelming because we’ve never had that. We’ve just never been exposed that,” interjected Pajot

They hired a sales agent upon their acceptance into Sundance and the film generated tons of buzz before it arrived at the festival resulting in a sales frenzy. The filmmakers wanted a simultaneous worldwide digital release, but theatrical distributors weren’t willing to give up digital rights so they opted for a self release. “There were a lot of offers, they approached us to purchase various rights. We felt we needed to get it out fairly quickly and in the digital way. A lot of the deals we turned down were in a little more of the traditional route. None of them ended up being a great fit,” said Pajot.

Several people were stunned when this indie doc about indie videogame developers opted to sell their film for remake rights to Scott Rudin and HBO. Pajot explained, “He saw the trailer and reached out a week or so before Sundance. That was sort of out of left field because it wasn’t something we were pursuing.” Swirsky added, “They optioned to potentially turn the concept into a TV show about game development…As a person who watches stuff on TV, I want this to exist. I want to see what these guys do with it.” The deal still left the door open for a more typical theatrical release. However that was only the start of their plan.

“We had spoken to Gary Hustwit (Helvetica). We sort of have an understanding of how he organized his own tours. We had to make our decision whether that was something we wanted to utilize. Five days after Sundance, we decided we would and were on the road 2 weeks after… Before Sundance this was how we envisioned rolling out…[We looked at] Kevin Smith and Louis C.K. and what they’re doing. We are not those guys and we don’t have that audience, but knowing core audience is out there, doing this made sense,” said Swirsky.

They proceeded to go on a multi-city promotional tour starting with seven dates and so far they have had 15 special events screenings of which 13 were sold out! This is separate from 37 theaters across Canada doing a one night only event. They also settled on a small theatrical release in NYC and LA. When talking about the theaters and booking, they said theaters saw the sellout screenings and that prompted interest despite the fact that the film was in digital release. They accomplish all of this with a thrifty mindset. “P&A was not a budgetary item we put aside and if an investment was required, we would dip into pre orders. We didn’t put aside a marketing budget for it,” said Swirsky. Regarding the pre order revenue, they sold a cool $150,000 in DVD pre-orders in the lead up to release of the film. From this money, they funded their theatrical tour.

While the theatrical release was small, it generated solid enough numbers to get held over in multiple cities and provided for vital word of mouth that will ultimately make the film profitable. The grosses were only reported for their opening weekend, but they continued to pack the houses in later weeks.”I don’t look back at the box office. The tour was more profitable than the theatrical…They both have the benefits, having theatrical it gets a broader audience. It was more a commercial thing than box office,” said Swirsky. “We are still getting inquiries from theaters. They still want to book it despite the fact it’s out there digitally,” said Pajot. “We had this sort of hype machine happening. We didn’t put out advertising. Everything was through our mailing that started with the 300 on our first Kickstarter and through Twitter,” said Swirsky. Now the team has over 20,000 people on their mailing list and over 10,000 Twitter followers. In order to keep this word of mouth and enthusiasm going, the filmmakers released 88 minutes of exclusive content – most of which didn’t make the final cut – to their funders, took creative suggestions from their online forum and sent out updates on the games the subjects of their film were developing over the course of the two years the film was in production.

Following the success the film has enjoyed in various settings, Indie Game: The Movie premiered on three different digital distribution platforms. If you were to try and guess what they were though, you would most likely only get one right. While, it is available on the standard iTunes, the other two means of access are much more experimental and particularly appropriate for this doc.

It is only the second film to be distributed by VHX as a direct DRM-free download courtesy of their, ‘VHX For Artists‘ platform. Finally, this film is reaching gamers directly through Steam which is a video game distribution platform run by Valve. This sterling doc is also only the second film to be sold through the video game service, where it was able to be pre-ordered for $8.99 as opposed to the $9.99 it costs across all platforms. This is perhaps the perfect example of the changing landscape of independent film distribution. Every film has a potential niche and most of these can arguably be reached more effectively through means outside the standard distribution model. Why should a fan of couponing have to go through hundreds of films on Netflix before even finding out a documentary about couponing exists, when it could be promoted on a couponing website?

As they are going into uncharted territory, both Pajot and Swirsky avoided making any bold predictions.”It’s just wait and see. It’s an experiment because we’re the first movie on Steam. We’re really interested to look at and talk about in the future. I don’t want to make predictions…I do think documentary lends itself to that kind of marketing though. We’re trying to not just be niche but there is power in that core audience. They are very easy to find online,” said Swirsky.

Just because they are pursuing a bold strategy doesn’t mean they were any less cost conscious. “The VHX stuff, it was a collaboration, so there were no huge costs. Basically subtitles, a little publicity costs from Von Murphy PR and Strategy PR who helped us with theatrical. Those guys made sense to bring on,” said Pajot. “A lot of our costs were taken up by volunteers. If they help us do subtitles, they can have a ticket event, a screening in their country,” added Swirsky.

They also note that a large amount of their profit has been in pre-orders. 10,000 people have pre-ordered one of their three DVD options priced at $9.99, $24.99 and a special edition DVD for $69.99 tied with digital. While the film focused on a select few indie game developers, they interviewed 20 different developers and the additional footage is part of the Special Edition DVD/Blu-Ray. That might explain why it’s their highest seller.

All this doesn’t mean that any of the dozens of other options are no longer usable. Quite the contrary, they have also taken advantage of the Sundance Artist Services affiliations to go on a number of more traditional digital sites. Increased views of a film even if on non traditional platforms can mean increased web searches and awareness and could be used to drive up sales on mainstay platforms.

The real winner though is ultimately the audience. For the majority of the world that doesn’t go to Sundance or Cannes each year, this is how they can discover small films that were made with them in mind. The HBO deal aside, this is bound to be one incredibly profitable documentary that introduces a whole new crowd to quality art-house cinema. “We are still booking community screenings. If people want to book, they can contact us…We are thinking maybe we might do another shorter tour at some point,” said Pajot.

Here’s to the independent film spirit, alive and well.

Update Feb 2013: The creators of Indie Game have written their own case study discussing the many tools and techniques they used. Head over to their website for the full study.

Orly Ravid August 16th, 2012

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, DIY, Film Festivals, iTunes, Marketing, Publicity, Theatrical

Tags: crowdfunding, DIY distribution, documentary, game developers, Gary Hustwit, independent film, Indie Game, James Swirsky, Kevin Smith, Kickstarter, Lisanne Pajot, Louis C.K., self distribution, Steam, Sundance Artists Services, Sundance Film Festival, VHX, VHX for Artists

Publicizing Your Film at a Festival

TFC reached out to Film Independent/Los Angeles Film Festival’s Director of Publicity and Communications, Elise Freimuth, to discuss to the “Do’s and Don’ts” of working with Publicists on the Film Festival circuit. The following are her “insider” thoughts on the subject…

With so many independent filmmakers going the DIY route, more and more of you are taking on publicity and marketing responsibilities. As a result, you need to educate yourselves on the essentials of the trade. Even if you do end up hiring a publicist, it’s important to understand some basics so you can be empowered and know the right kind of questions to ask when selecting a publicist or putting together a PR strategy with them.

Many indie filmmakers make the mistake of thinking about publicity when they get accepted into a film festival, but in truth, you need to start thinking about PR when you’re putting your budget together. Costs need to be factored in early on for possibly hiring a unit photographer, hiring a publicist once you do get accepted to a festival, paying for room and board for talent to attend a festival and creating press materials.

Create your press materials early! So many filmmakers put these off and then have to scramble to pull assets together when they get accepted into a film festival. A publicist is usually hired about 1-2 months before a festival, so it doesn’t give them much time to work on your film. Give them as much time as possible to pitch your work by giving them a package of nice materials. They may have suggestions to spice things up a bit, but at least they’re not having to start from scratch.

We’re in the moving pictures business for a reason– we like telling stories with images. And images are incredibly important when you’re promoting your film. Creating high-quality still images from your film will go a long way in helping you promote your work and save you from a huge headache down the road. If you can’t afford a unit photographer to come in for a few days during the shoot, then have a photographer friend or someone from your camera department (so many video cameras can create beautiful stills) take high-quality still photos for you. If you have name talent, you should schedule a photographer on the days you’ll be shooting key scenes with them. Your photos should properly convey the tone (comedy vs drama) and reveal something about the character or story. A generic close-up of a character reveals nothing—it could be from any film.

Journalists want photos that are going to help them tell the story about your film and they’re going to want to grab their readers/viewers. Photos should be high resolution (at least 300 dpi), and most news outlets prefer horizontal. When selecting images, keep in mind that you may need to get key talent to sign off on these, so go through their representatives and have them do their “photo kills” early so you’re not chasing them down 3 weeks before a festival. Also, you really only need 2 or 3 great still images. When audiences start to see the same photo running online and in magazines and newspapers, it’s easier for them to recognize your film. And given the time constraints journalists have nowadays, the last thing they want to do is troll through 20 pictures. They want to look at a few and pick one.

Following these guidelines will also help film festivals. Their marketing departments need to put together program books, ads and build their website, and it’s really hard when filmmakers submit low resolution photos in non-traditional formats. You’ll also want to consider holding back a few photos for exclusives down the road when you get a theatrical or digital release. Some publications like USA Today, Los Angeles Times, New York Times and Entertainment Weekly like to use exclusive photos for their movie previews and articles. Plus, it’s a great way to do an extra push and leak out exclusive content when you’re releasing your film.

Gone are the days of putting your clips and trailers on bulky and expensive beta tapes. Most festivals and broadcast/online outlets just require a digital file, preferably in HD that you can e-mail, post on your website or share via file transfer websites. Just like with photos, a couple clips of key scenes that convey your story and tone are all you really need. Clips should only be about 30-45 seconds long. Trailers are nice, but they’re not terribly necessary at this point. If your film gets acquired, they’re just going to cut a new trailer and the process can be rather pricey. Usually broadcast outlets aren’t going to show festival film trailers, unless there are huge stars involved. There are some online outlets that may run your trailer, but again, don’t break your back over this. If you do decide to do a trailer, just make sure it’s no longer than a minute and a half and it should be well-edited and tell your story without giving everything away.

Production notes are really handy for journalists to refer to when prepping for interviews with you or your talent, or to fact check when they’re writing reviews or stories on your film. These notes do not need to be 35 pages long. Keep them sweet, short and simple. Include a log-line (1 line), short synopsis (2-3 lines), long synopsis (2-3 paragraphs)—these also help the festival staff when they’re putting together their materials. You’ll want to include short bios (1-2 paragraphs) on yourself, key crew and cast. A director’s statement is always nice, but not necessary. This should be 1-3 paragraphs and can explain your reason for making your film, explain controversial elements behind the film, the style you chose, etc. Don’t include reviews and interviews from other publications in your production notes because journalists don’t need to see other people’s work in your notes. A full list of credits is also essential as film critics need to include this information when they file their review. If they don’t have the full credits, this sometimes prevents them from actually filing a review of your film!

Posters are lovely to have as a souvenir, but not necessary for publicizing your film at a festival. The festival will ask you for these because they’ll sometimes display them for a day or two at the theater venue or in their filmmaker lounge, but that’s about all they use them for. Posters are expensive to make, so if you’re on a budget, this is the thing to cut. Maybe opt for some creative hand-out material with your screening schedule on it if you’re on a budget and are really keen on printed material. A small postcard is easy to hand out to people you meet. Some filmmakers get even more creative and hand out matchbooks, coasters, buttons and more to go along with the theme of their film. But again, all of these things are just fun add-ons if you’ve got the money for them.

If you start getting interview requests and screener requests (see paragraph about screeners) before the festival begins, hold off on setting these up until you’ve hired a publicist or put a PR strategy in place. The last thing a publicist wants is to come on board a film and find out you’ve set up a bunch of interviews without them. Or egads! Set it with someone they know could potentially attack your film or not fit in line with the strategy.

Don’t hire a publicist if you haven’t gotten into a film festival or have a theatrical/digital release. They’re more than happy to take your money, but you won’t get a return on their services if you’re not actually screening your film anywhere. So many filmmakers think they need to hire a publicist as soon as the film is done, but you’ll just be spending dollars that can be used more effectively once you secure that festival slot. You should aim to hire your publicist within 1-2 months of your festival screening, but start asking your sales agent, friends and fellow filmmakers for recommendations and put together your wish list early. Once you find out you’re in a festival, you can start making the calls to these publicists and set up meetings. These meetings are kind of like a first date or a dance—you need to find out if you like each other, can work together and they can execute the proper strategy for your film. They should obviously like your movie, but they should also have a strategy and be able to openly talk with you about potential negative reactions that could result from the press and industry, weaknesses in your film and how to navigate those, and be able to work closely with your sales agent (their strategies need to align). In some cases, the publicist is really there to support the sales agent, and having one who understands distributors is also helpful. Having a cheerleader isn’t enough—that’s what your parents are for. Your publicist should have a plan, know the press attending and be able to strategically execute that plan. For festivals like Sundance, Toronto, Cannes and SXSW, the price you pay will be higher because it needs to cover room and board for the publicist. Expect to pay anywhere from $7-12K. Believe it or not, the costs for sending a team of publicists to these festivals ends up breaking even for them. They’re working on your film because they’re passionate about you and your work. For festivals like the Los Angeles Film Fest, AFI, New York Film Fest and Tribeca, there are tons of locally based publicists in entertainment, so you have a wealth of people to choose from. If you’re playing in LA, select a LA-based publicist and in New York, New York. Why? So you don’t have to pay more for their travel. PLUS, they’re going to be a lot more familiar with the local press attending that festival. Expect to pay $3-7K for these festivals.

Whether you hire a publicist or not, don’t blow your wad at the very beginning. It’s incredibly exciting for you now that you’re playing in a film festival. You want to see a ton of press breaks and have everyone interviewing you and your talent, but you need to reign it in. You want people to discover your film and if you go hog wild with interviews, then no one will want to interview you or your talent when the film finally gets that theatrical/digital release. It’s like turning the heat on to boil a pot of water. You want that water bubbling for your festival PR campaign—you don’t want it boiling over. Work on getting included in some festival curtain raisers—i.e. previews that mention films to catch or look out for. A handful of interviews are all you really need with some key outlets that cater to the audience you’re trying to target.

Decide whether it’s the industry you want to focus on, or raise awareness about a certain issue, or reach out to a certain fan base. BE TARGETED. If you’re a small documentary or narrative with no stars, then Access Hollywood will not want to cover you. They only want the A-list talent. Be REALISTIC and SMART about the type of press you can get.

Communicate with the festival PR staff. If you’re doing DIY, then reach out to them personally. If you have a publicist, make sure they get in touch with the staff so they can be notified of press opportunities that might fit your film, or get some leads. If you’re on your own, the festival PR staff is there to help you. They have tons of films they need to publicize and are mostly focusing on publicizing the festival as a whole, not individual films. They can’t play favorites because all the filmmakers are their children here, but they can give you advice on putting together a PR strategy, point you towards journalists they think might be interested in your film and how to reach out to them. They’ll appreciate that you’re thinking about PR in a smart way and not just asking for their press list so you can blast out multiple e-mails and invites.

A note on screeners. BE CAREFUL WITH THESE. The festival PR staff may ask you for copies of screeners, but you don’t have to provide these. It should be an option. The risk in providing these to the festival is that any accredited journalist can walk in and watch your film on a laptop, small TV or check it out, and you won’t know who it is. They can always pass along screener requests from the journalist directly to you or your publicist so you have more control over who is seeing your film early (the same goes for acquisitions execs! Let your sales agent send these out!!) It’s really best to protect your screeners and only give them to journalists if it works with your PR strategy. Some journalists may need to see the film early for a curtain raiser or feature and are nice about only including films they like. There are other journalists who could potentially badmouth your film before the festival screening. Make sure you or your publicist knows the intent of the journalist. Some films just play better on the big screen with an engaged crowd and some films play better on your laptop with a box of Kleenex at your side. Figure out how your film plays and let that help guide you on whether you want to share screeners.

Orly Ravid May 31st, 2012

Posted In: DIY, Film Festivals, Publicity

Tags: Elise Freimuth, festival publicity, film festival, Film Independent, film publicity, LA Film Festival, postcards, posters, PR assets, PR budget, PR strategy, set photography, working with a publicist

Navigating digital distribution, 11 things to consider

This post by Orly Ravid was published originally on the Sundance Artists Services blog April 15, 2012

1. CARVE OUT DIY DIGITAL:

Distributors and Foreign Sales companies alike often want ALL RIGHTS and including ALL DIGITAL DISTRIBUTION RIGHTS.

No matter what, at least CARVE OUT the ability to do DIY Digital Distribution yourself with services such as: EggUp, Distrify, Dynamo Player, and/or TopSpin, off your own site, off your Facebook page, and also directly to platforms that you can access. Platforms and services can almost always Geo-Filter thereby eliminating conflict with any territories where the film has been sold to a traditional distributor and often times a distributor will not mind that a filmmaker sells directly to his/her fans as well in any case.

2. PLATFORMS ≠ AGGREGATORS ≠ DISTRIBUTORS:

Platforms are places people go to watch or buy films. Aggregators are conduits between filmmakers/distributors and platforms. Aggregators usually focus more on converting files for and supplying metadata to platforms and that’s about it. Marketing is rarely a strong suit or focus for them but it should be for a distributor, otherwise what’s the point? Aggregators usually don’t need rights for a long term and only take limited rights they need to do the job. Distributors usually take more rights for longer terms. Sometimes distributors are DIRECT to PLATFORMS and sometimes they go through AGGREGATORS. It makes a difference because FEES are taken out every time there is a middleman. Filmmakers should want to know the FEE that the PLATFORM is taking (because it’s not always the same for all content providers though usually it is other than for Cable VOD, for example) and know if a distributor is direct with platforms or goes through an aggregator. Also, filmmakers should have an understanding what each middleman is doing to justify the fee. On the aggregator/distributor side, we think 15% is a better fee than 50%, so have an understanding of what services are included in the fee. If a distributor is not devoting any time or money to marketing and simply dumping films onto platforms, then one should be aware of that. Ask for a description in writing of what activities will be performed.

3. THINK OF DIGITAL PLATFORMS AS STORES AND CUSTOMIZE A PLAN THAT IS RIGHT FOR YOUR FILM:

A film should try to be available everywhere however sometimes that is too costly or not possible and when that is the case one should prioritize according to where the film’s audience consumes media. Think of digital platforms as retail stores. Back in the DVD days (which are almost gone), one would want a DVD of an indie film in big US chains such as Blockbuster and Hollywood Video but especially a cool, award winning indie would do well in a 20/20 or Kim’s Video store because those outlets were targeting a core audience. With digital, it’s the same. While many filmmakers want to see their films on Cable VOD, some films just don’t work well there and delivery is expensive. Some films make most of their money via Netflix these days and won’t do a lick of business on Comcast. Other films do well on iTunes and some die there whereas they might actually bring in some business via Hulu or SNAG. Docs are different from narrative and niches vary. Know your film, its audience’s habits and resolve a digital strategy that makes sense. If money or access is an issue, then be strategic in picking your “stores” and make your film available where it’s most likely to perform. It may not be in Walmart’s digital store or Best Buy’s. Above all, if you dear filmmaker have a community around you (followers, a brand), your site(s) and networks may be your best platform stores of all. Though there is something to be said for viewing habits so I do recommend always picking at least a couple other key digital storefronts that are known and trusted by your audience.

4. TIP FOR CABLE VOD LISTINGS:

By now many of you may have heard that it’s hard to get films marketed well on Cable VOD platforms. Often the metadata either isn’t entered or entered incorrectly and it’s nearly impossible to fix after it goes live. Hence, oversee the metatags submitted for your film and check immediately upon release. Also, since genre/category folders and trailer promotion are not always an option for every film, it is the case that films with names starting in early letters of the alphabet (A-G) or numbers can perform better. Then again, there’s a glut of folks trying that now so the cable operators are getting wise to this and not falling for it. All the more reason to focus on marketing, marketing, marketing your title, so audiences are looking for it and not just stumbling upon your film in the VOD menu. There are only going to be more films to choose from in the future, not fewer.

5. ART for SMALL:

Filmmakers, if there is one thing I must impart to you once and for all it’s this: TAKE GOOD PHOTOGRAPHY!!! Take it when making your film. Remember, most marketing imagery if not all for digital distribution (which will be all of “home entertainment”) must work SMALL so create key art and publicity images that also work well small and in concert with the rest of your campaign. Look at your key art as a thumbnail image and make sure it is still clearly identifiable.

6. KNOW YOUR DIGITAL DISTRO GOALS AND PLAN AHEAD:

I have seen distribution plans wasted because a vision for the film’s path was not resolved in time to actualize it properly. If your film is ripe for NGO or corporate sponsorship and you want to try that, you will need loads of lead time (6-12 months at least!) and a clear distribution plan to present to potential sponsors (who will always need to know that before agreeing). If making money is a top concern, then know how YOUR FILM’s release is mostly likely to do that and plan accordingly. It may be by collapsing windows or it may be by expanding them. All films are different and that’s why it’s best to look at case studies of films with similar appeal to yours. And if showing the industry that your film is on iTunes matters to you for professional reasons more than financial then know that is your motivator but know that getting a film onto iTunes does not automatically lead to transactions, marketing does.

7. TIMING IS EVERYTHING | WINDOW WATCHING:

Digital distribution often has to be done in a certain order if accessing Cable VOD is part of your plan. That is not the only reason to consider an order and an order is not always needed, but it can be a consideration. Sometimes Cable VOD is not an option for a film (films often need a strong theatrical run before they can access Cable VOD) and, in this case, the order of digital is more flexible and one can be creative or experiment with timing and different types of digital. However, Cable VOD’s percentage share of digital distribution revenues is still around 70% (it used to be nearer to 80%) so if it’s an option for your film, it’s worth doing, at least for now.

It is very often the case that if your film is in the digital distribution window before Cable VOD (on Netflix for example), that will eliminate or at least dramatically diminish the potential that Cable MSO’s (Multi System Operators) will take the film or even that an intermediate aggregator will accept it. There is more flexibility with transactional EST (electronic sell through) / DTO (download to own) / DTR (download to rent) services such as iTunes but much less flexibility with YouTube (even a rental channel) or subscription or ad-supported services such as Netflix (subscription) or Hulu (which is both). Films that opted to be part of the YouTube/Sundance rental channel initiative (such as Children of Invention) could not get onto Cable VOD after. The Film Collaborative has to hold off on putting films in its YouTube Rental Channel if cable VOD is part of the plan. Of course, there are exceptions to every rule due to relationships or a film proving itself in the marketplace, but better to plan ahead than be disappointed.

Companies such as Gravitas are also programmers for some of the MSOs so they have greater access to VOD, but they too discourage YouTube rental channel distribution before the Cable VOD window and they do Netflix SVOD (Subscription Video on Demand), distribution after. In general, people often do transactional platforms first and ad-supported last with Netflix being in the middle unless it’s delayed because of a TV deal for example. This is not always the case and some distributors have experienced that one platform can drive sales on another but in my opinion it depends on the film and habits of its audience. You should know that Broadcasters such as Showtime will pay more if you do your Netflix SVOD after their window rather than before.

WINDOW WATCHING: If you stream or distribute digitally before Cable VOD for example, you will often lose that opportunity so timing is key. And of course festivals will often not program a film if it’s available digital or at all commercially. For documentaries, one has to be mindful about the EDUCATIONAL window (though this usually most relates to DVD). Broadcast and SVOD are competitive with each other so compare options in terms of fees and timing for best distribution results and maximum benefits. Sometimes VOD is best BEFORE theatrical (it’s called Reverse Windowing and Magnolia does that for example, sometimes). Sometimes Ad Supported VOD (AVOD or FOD (free VOD)) (e.g. regular HULU) or Broadcast airings are seen as useful for maximum awareness, relatively significantly revenue generating, and/or good for driving transactional VOD. Whereas sometimes AVOD or FOD is seen as cannibalizing business and is delayed. So again, know your strategy based on both your audience / consumer and your goals.

8. THE DEVIL IS IN THE DEFINITIONS

DEVIL IS IN THE DEFINITION: Remember that the term VOD means or includes different things to different users. The terms in the space are becoming more customary but they are not fully standardized so be sure to have ALL terms related to digital rights DEFINED. And the space keeps changing so be sure to stay current.

There is no standard yet for definitions of digital rights. IFTA (formerly known as AFMA) has its rights definitions and for that organization’s signatories there is therefore a standard. But many distributors use their own contracts with a range of definitions that are not uniform. When analyzing distribution options, be aware that terms such as VOD can mean different things to different people and include more or fewer distribution rights and govern more or fewer platforms.

Consider the term “VOD”. In some contracts, it’s not explicitly defined and hence can mean anything and everything. IFTA is clear to categorize it as a PayPerView Right (Demand View Right) and limit it to: “transmission by means of encoded signal for television reception in homes and similar living spaces where a charge is made to the viewer for the rights to use a decoding device to view the Motion Picture at a time selected by the viewer for each viewing”.

However in some contracts, it’s defined as “Video-on-Demand Rights,” meaning a function or service distributed and/or made available to a viewer by any and all means of transmission, telecommunication, and/or network system(s) whether now known or hereafter devised (including, without limitation, television, cable, satellite, wire, fiber, radio communication signal, internet, intranet, or other means of electronic delivery and whether employing analogue and/or digital technologies and whether encrypted or encoded) whereby the viewer is using information storage, retrieval and management techniques capable of accessing, selecting, downloading (whether temporarily or permanently) and viewing programming whether on a per program/movie basis or as a package of programs/movies) at a time selected by the viewer, in his/her discretion whether or not the transmission is scheduled by the operator(s)/provider(s), and whether or not a fee is paid by the viewer for such function/service to view on the screen of a television receiver, computer, handheld device or other receiving device (fixed or mobile) of any type whether now known or hereafter devised. Video-on-Demand includes without limitation Near VOD (“NVOD”,) Subscription Video-on-Demand (“SVOD”,) “Download to burn”, “Download to Own”, “Electronic Sell Through” and “Electronic Rental,” for example. This example includes everything and your kitchen sink.

One has to ask if a definition of VOD or another type of digital right includes “SVOD” (Subscription Video on Demand) and includes subscription services such as Netflix and Hulu Plus. Why does this matter? Well if the fee to the distributor and/or to you is the same either way then it may not matter. If there’s a difference in fees depending on the nature of distribution, then it will. Recently an issue in a deal came up with respect to distinguishing ad-supported specifically from general “free-streaming”. Is ad-supported governed by a “free-streaming” rights reference? Why wonder, Just spell it all out; better to be safe than _____.

Another example, if a contract notes a distributor has purchased “VOD Rights” but does not define them, or defines them broadly, then do they have mobile device distribution rights as well? The words “Video-on-Demand” sometimes are used only to refer to Cable Video on Demand and other times much more generally. In a “TV Everywhere” (and hence film everywhere) multi-platform all-device playable universe, the content creator needs to know.

The devil is in the definition that you must read carefully BEFORE you sign on the dotted line. Know what you want for and can do for your film in terms of distribution and carve it up and spell it out.

9. PLAN FOR FUTURE: Digital distribution in Europe is not as mature as it is in the US but it’s growing. The key platforms and categories of VOD now may not be key down the road. Again, do deals wisely and plan for the future. One way may be to set revenue thresholds for contract terms to continue. Or allow for terms to be reviewable and adjustable into the Term.