TFC’s Distribution Days is upon us!

Next week, The Film Collaborative is holding a free virtual distribution conference, Distribution Days, which will offer concrete takeaways on the state of indie distribution and how filmmakers can navigate it. Attendees will hear from exhibitors, distributors, consultants, and filmmakers, some with case studies, as they describe and reflect on the landscape.

This conference hopes to help filmmakers develop critical thinking skills around distribution by looking at what is and what is not viable within a traditional distribution framework. It will also offer some alternative approaches. Willful blindness or a doomsday mindset are equally unproductive.

So, we are offering this pre-conference primer to set the tone, take stock of what myths are out there, and talk about what thought leaders in this space are coming up with as ways to deal with the current landscape.

Here we go!

Remember the days when creators and distributors were lying back in their easy chairs, proclaiming their satisfaction with how independent cinema has been evaluated by the marketplace? Yeah, we don’t either…and we’ve been in the industry (in the U.S.) for more than two decades. Nevertheless, there is a pervading sense that the state of independent film has never been worse—and that we’ve been going downhill from this mythic “better place” ever since Sundance was founded in 1978.

Why do we insist on bemoaning a Paradise Lost when the truth is that being a filmmaker has never been a paradise? Filmmakers have always been confronted with predatory distributors, dense and confusing contract language, onerous term lengths, noncollaborative partners, lack of transparency, and anemic support, if any (just to name a few). For an industry that prides itself on creating and shaping stories that speak to diverse audiences, we should be better at articulating truer narratives about our field.

It doesn’t help that, at Sundance this past year, all one could talk about was how streamers were “less interested in independent film than a few years ago, preferring [instead] to fund movie production internally or lean on movies that they’ve licensed” and how Sundance itself was “financially struggling, presenting fewer films than in previous years and using fewer venues.” (https://www.thewrap.com/sundance-indie-film-struggles-working-business-model) Still others like Megan Gilbride and Rebecca Green in their Dear Producer blog have put forth ideas how Sundance should be reinvented completely.

But we all know that independent film isn’t just about Sundance. We have heard a lot of discussion recently about the need to reshape the narratives we tell ourselves regarding the state of the independent film industry.

Distribution Advocates, which is also doing great work chasing the myths vs. the realities of the field, also believes that we must all question “some of our deepest-held beliefs about how independent films get made and released, and who profits from them.”

In their podcast episode about Exhibition, economist Matt Stoller remarked how “weird” it is that even with all the technology we possess connect audiences, we’re still so “atomized” that all that rises to the top is whatever appears in the algorithm Netflix chooses for us in the first few lines of key art when we log in (and we will note that even the version of the key art you see is itself based on an algorithm).

But is it really all that strange? One of the main reasons that myths exist is that someone is profiting from perpetuating them. The same with networks and platforms and algorithms. And the more layers of middlemen and gatekeepers there are, the harder it is for us to see the forest for the trees. Keeping us in our algorithmically determined silos numbs us into not minding (actually preferring) that we are watching things—or bingeing things—from the safety and comfort of our living rooms. The ability to discover on our own content that aligns with our true interests or consuming content in a communal space has disappeared the same way that the act of handwriting has…we used to be able to do it but haven’t done it in so long that it feels unnatural and too time-consuming to deal with.

Brian Newman / Sub-Genre Media acknowledges that the problems remain real, but that what everyone is calling crisis levels seems to him merely a return to norms that were in place before the bubble burst. No one, he says, is coming to rescue “independent film”—certainly not the streaming platforms, which merely used it as necessary to build a consumer base.

Many have posited myriad ideas about how to bypass the gatekeepers. Newman echoed what TFC has been recently discussion internally: that instead of many competing ideas, we need them to be merged into one bigger idea/solution. Like, for example, an overarching solution layer run by a nonprofit on top of each public exhibition avenue that will aggregate data and help filmmakers connect audiences to their content. A similar idea was also discussed at the last meeting of the Filmmaker Distribution Collective in the context of getting audiences into theaters.

By exclaiming that “No one is coming to the rescue,” Brian really means that we are all in this together, and that it’s going to take a village.

We agree, but a finer point needs to be made.

Every choice we make moving forward—whether you are a filmmaker, distributor, theater owner, or festival programmer, what have you—could possibly be distilled into either a decision for the independent filmmaking public good…or for one’s own professional interest. Saying that a non-profit should come in and offer a solution layer to aggregate data is all well and good until it threatens to put out of business someone whose livelihood is based on acquiring and trafficking in that data. How refreshing was it to be reminded at Getting Real by Mads K. Mikkelsen of CPH:DOX that his festival has no World Premiere requirements? It reminds us of the horrible posturing and gatekeeping film festivals do in the name of remaining relevant and innovative. For us to truly grow out of the predicament we are in, some of us are going to have to voluntarily release some of the controls to which we are so tightly clutching.

Keri Putnam & Barbara Twist have an excellent presentation on the progress of a dataset they are putting together of who is watching documentaries from 2017 – 2022. They provide some other data that was very sobering:

Film festivals: comparing 2019 numbers to 2023 – there was a 40% drop in attendance;

Theatrical: most docs are not released in theaters and attendance is down even for those that are released.

But they also note that there is really great work being done in the non-theatrical space— community centers, museums, libraries – that is not tracked by data. TFC’s Distribution Days offers two sessions on event theatrical and impact distribution, so we’ll be able to see a tiny bit of that data during the conference.

We also know that the educational market is still healthy, and that so many have remarked of the importance of getting young people interested in film…so we have three sessions where we hear from the Acquisitions Directors of 11 different educational distributors.

We also have a panel from folks in the EU who will provide advice on the landscape and how best to exploit films internationally and carve our rights and territories per partner. And we’ll speak to all-rights distributors about what kinds of films they see doing well, what they are doing to support filmmakers—and what their value proposition is in this marketplace.

We have a great panel on accessibility, and two others that relate to festivals and legal agreements.

Starting off with a keynote from noted distribution consultant and impact strategist Mia Bruno, the 2-day conference aims to summarize the state of the industry while providing thought provoking conversations to inspire disruption, facilitate effective collaboration, and to aid broken hearts.

Regardless of whether current days are better or worse than the heydays of Sundance and the independent film of yesteryear, Distribution Days will identify the current obstacles of the independent film distribution landscape, and what we can hold on to—as a commonality—to evolve the landscape together in the future.

If you look a little deeper, you will see that, despite all the challenges, filmmakers have and can still achieve “success” when they understand the terrain, (sometimes) work with multiple partners with a bifurcated strategy, protect themselves contractually, and maintain and grow their own personal audience.

We hope you will join us. And for those of you that cannot make all of the sessions we are offering live on May 2 & 3, you’ll be able to catch up on what you missed via The Film Collaborative website after the conference is over.

We look forward to seeing you next week! And if you have not registered yet, you can do so for free at this link.

David Averbach April 25th, 2024

Posted In: case studies, Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms, DIY, Documentaries, education, Film Festivals, International Sales, Legal, Marketing, Theatrical

The Implosion of Distributor Passion River… And What it Means for You

by Pat Murphy

Pat Murphy is a documentary filmmaker and editor. His latest film, Psychedelia, uncovers the history and resurgence of psychedelic research. It was sold to universities, nonprofits, international broadcasters, and the streaming service Gaia.

Passion River Films was one of those rare distributors. In an industry with plenty of shady companies, they had a reputation for honesty. Some of the most influential figures in the independent documentary distribution space referred their colleagues to them. And yet under the hood, in that nondescript office building in New Jersey, the operation at Passion River was in serious trouble. And it had been for some time.

Founded in 1998 by Allen Chou, Passion River’s catalog focused on educational documentaries, which they sold to universities, libraries, nonprofits, and the DVD/VOD market. Unlike a lot of distributors, they were flexible with filmmakers. They allowed them to put a cap on distribution expenses and reserve certain rights for themselves. I signed my film Psychedelia with them in 2021 and got the feeling that it was in good hands.

Yet for the past few years, Passion River had been withholding accounting reports and payments to filmmakers. Communication slowly dropped off and eventually went completely silent. Requests for information were ignored. And then earlier this year, they announced—in an unexpected, evasive, and self-serving manner—that they were insolvent. Hundreds of filmmakers lost many thousands of dollars, and some are still dealing with the logistical nightmare it caused for their films.

What happened at Passion River? How did it slip by undetected? We may never know. But Passion River’s collapse should serve as a stark warning to all filmmakers of the precarious nature of film distribution. It comes during a tumultuous time for the industry and the larger economy. It’s a bombshell story that demonstrates the inadequacy of systems to deal with this situation. And it shows how the hardship lands squarely on the creatives who make this industry possible.

What We Know

If you’re pressed for time, here’s a summary of the situation:

- In January, Passion River announced that they had become insolvent, and were selling the “majority of their assets” to another distributor called BayView Entertainment.

- Once filmmakers were connected with BayView, they were told that they had purchased the “assets, but not the liabilities” of Passion River.

- Passion River had been withholding accounting statements and payments to producers in 2022 and earlier, leaving producers without any record of the money they were owed. BayView said they were not responsible for these payments.

- Filmmakers had nobody to contact. Passion River abandoned its offices, shut down their phone lines and email domains, and transitioned their employees to new positions at BayView.

- The total damage in lost payments, although difficult to determine, is likely in the multiple six figures. There appears to be no accountability on the part of Passion River.

Keep reading to get the full story, as well as distribution strategist Peter Broderick’s key takeaway.

Announcing Their Insolvency

On January 31, 2023, Josh Levin (Head of Sales and Acquisitions at Passion River), sent the following note to most (but not all) of the filmmakers that had contracts with the company:

I have some news to share – the parent company of Passion River Films lost the ability to meet its obligations and has sold the majority of its Passion River assets to BayView Entertainment, LLC. BayView is a venerable, much larger film distributor with an outstanding 20+ year reputation in film distribution.

I am sure you have questions about what this transition means for you and your films. These questions can best be answered by speaking directly with Peter Castro, the VP of Acquisitions at BayView. Please email Peter at ***** to set up a call. Peter is looking forward to speaking with you.

According to their contract with filmmakers, Passion River was supposed to send accounting statements and payment 60 days after the end of each quarter. This meant that all sales that Passion River made in the fourth quarter of 2022 (October-December) were supposed to be reported and paid by March 1, 2023.

This timing was particularly unfortunate for me and my film, which had been released in Summer 2022. We secured a streaming deal with Gaia and it was released on TVOD. Gaia pays their licensing fee in two installments. So, I was waiting on the second payment ($9,750) plus all the TVOD and educational sales from my film’s release. Those payments came in the fourth quarter 2022, so I was waiting for that statement and payment to come by March 1, 2023.

Naively, I responded by asking Josh Levin about his own well-being. While I found Passion River’s work a bit sloppy and frustrating, I took Josh to be an honest broker. I was relieved to hear that he was going to work for BayView as Vice President of Sales [LinkedIn account required to view]. To me, the whole thing was portrayed as a standard acquisition. I thought that I would work with Josh as before, but this time under a new company name. I assumed my payment of over $10,000 would come from the new company.

But by the time I was able to get through to Peter Castro (VP of Acquisitions at BayView), it was already March 3, 2023. Neither my accounting statement nor my payment had arrived. My conversation with Peter turned out to be extremely unsettling. This was no ordinary acquisition. BayView had purchased the “assets but not the liabilities” of Passion River.

Yes, that’s a thing. Apparently BayView did not actually purchase the rights to our films, and therefore they were not responsible for any outstanding payments from Passion River. And they had no way of collecting that money or telling us what happened to it. We had the option to sign new contracts with them, at a less favorable split than we had with Passion River.

As for getting answers on what happened over at Passion River, such as why they became insolvent or what they did with the money that was due to us? There was no avenue to explore those questions. Josh Levin, now employed by BayView, said he was forbidden to talk about anything that happened at Passion River. Allen Chou, the president of Passion River, whom most people had never met, was elusive. The voicemail boxes at Passion River were full and their email domains would bounce.

I was devastated. And furious. Like most folks, my film was an independent labor of love over several years. What made it sting even more was the fact that Passion River did not actually secure my streaming deal with Gaia. Gaia heard about my film through my own marketing efforts, and as a good faith move towards Josh Levin, I decided to give Passion River their 25% commission on that deal.

As it turns out, I was not alone.

Finding the Others

Without any helpful information, we began finding each other through online forums like The D-Word and the Facebook group, Protect Yourself from Predatory Film Distributors [Facebook account required and one must join the group to view]. Eventually, we gathered on a private channel, so we could share information and piece together whatever we could from our own investigations and experiences.

Each film’s situation was different, but pretty much everybody reported the same experience working with Passion River: disorganized workflows, poor communication, improper accounting, missed payments, and even downright deception.

Filmmaker Jacob Bricca of Finding Tatanka said, “They were responsive at first, informing me of sales they had made and giving me regular statements showing that I was slowly paying off the charges associated with creating the DVD and distributing the film. This communication dropped off as the years went on. I finally contacted them again in mid 2022. These inquiries went unanswered. Finally, after repeated attempts to get a reply, I got a statement in early 2023 that I was owed over $1,400… I have never seen a penny from Passion River.”

Jacob was the only filmmaker I ever spoke to that had received an accounting statement for the fourth quarter of 2022. The rest of the filmmakers did not receive any accounting statements for that quarter, leaving them without a written document of what they were owed. Many reported incomplete accounting prior to the 4th quarter as well. Time and again, filmmakers were told by Josh Levin that he would “ping accounting” about their issue. However, filmmakers received no response or follow through.

While all this was happening, Passion River was still actively marketing their catalog. In March of 2023, I found an End of the Semester Sale on their website, which was active from December 1, 2022 to January 31, 2023. My film was featured prominently on the page, even though I had never received a single report of an educational sale. The fact that they would deliberately run a sale as late as December (when the sale to BayView must have been known), raises serious ethical questions.

“Passion River is not the first, or last, film company to go out of business,” said Emmy-and Peabody-winning and Oscar-nominated producer Amy Hobby. “But the lack of transparency, failed reporting, and missed payments simultaneous to continued recoupment off filmmakers’ backs is egregiously unethical.”

Attempts at a Resolution

Besides dealing with the financial fallout from Passion River, our other big question was about what to do with our films moving forward. They were still up on VOD platforms, but where was that money going? And what do we do now that we don’t have a distributor?

Director Kim Laureen, of Selfless, signed with Passion River in 2020: “Since day one I have had to chase reports and payments.” Unlike me, she was never notified of the sale to BayView. With nobody to contact about her pending payments, Kim sent a tweet out to Passion River. That got the attention of Peter Castro, VP of Acquisitions at BayView. Kim had a conversation with Peter, in which she explained why people were frustrated. Peter agreed to host a Zoom call with Kim and any other filmmaker who felt mistreated. Kim and I put out notices to the group of filmmakers about a “virtual town hall” on March 17, 2023.

Peter must have been surprised when he logged on to zoom and found dozens of angry filmmakers asking tough questions and demanding answers. Consultant Jon Reiss also joined and was instrumental in getting straight answers. The conversation went on for almost an hour and a half. We were able to confirm the following during that meeting:

- It’s unclear exactly what BayView purchased from Passion River, but it allowed them to collect revenue off of our films without a contract.

- Since BayView was currently collecting revenue on our films, they would send us payment for 2023 sales whether or not we signed new contracts with them.

- For those of us who wanted to move on to new distributors, BayView would facilitate that.

It sounds like many people ended up signing with BayView. But most of the people I’ve spoken to decided to move on to new distributors or go a DIY route without any distributor. Figuring out how to do all this and getting Allen Chou to cooperate was full of complexities over the ensuing months:

- Many distributors required an official release from Passion River. Through a collective effort led by producer Amy Hobby, Allen Chou wrote an official letter on May 9, 2023. This was his first communication to us, more than four months after the transition.

- Passion River had used an aggregator called Filmhub to upload many of our films to TVOD platforms. We were able to transition accounts with a representative there. In this scenario, the filmmaker keeps 80% of TVOD revenue, rather than giving Passion River or BayView their commission.

- BayView sent us accounting statements for Q1, as promised, on May 15, 2023.

Legal Recourse

One of the biggest revelations for me was the inadequacy of the legal system to deal with this situation. When I signed my deal with Passion River, I went back and forth on the legal language endlessly. I did everything I thought I could to protect myself and spent thousands of dollars in legal fees to do so. And when Passion River blatantly breached the contract? There was no good answer on what to do.

One avenue the legal system provides is small claims court. It’s designed to get your case heard in front of a judge without the need for an attorney. One filmmaker, who wishes to remain anonymous, decided to go this route. Their lawyer told them it was a “clear-cut case.” The filmmaker and their partner had painstakingly put together a Statement of Reasons, outlining their relationship with Passion River and what they were owed. In New Jersey, the maximum allowance is $5K.

Small claims court was on Zoom, and Allen Chou was there with his attorney, Spencer B Robbins. When it came time to present, Robbins interjected with an arbitration clause that was in Passion River’s contract, stating that any dispute between the parties should be brought in front of an arbitrator. With that, the judge threw out the case. The filmmakers tried to make a rebuttal but felt they were not given a proper chance to speak.

The filmmakers were so distraught that they decided to cut their losses and move on. “It’s why people lose faith in the justice system,” said one of them. While it’s difficult to say how much Passion River withheld from filmmakers, we can make a general estimate. Passion River had around 400 films in their catalog. So even if each film was only owed $1k that would aggregate to $400k. Almost half a million dollars. Where all that money went remains unknown. And as far as we can tell, nobody involved has been held accountable.

Key Takeaways

Here we are almost a year later. Many have expressed anger and depressed feelings around the whole situation. Writing this article has brought up a lot of emotions. But it’s also made me determined to not give in to cynicism. We need to turn this awful situation into something productive. In an attempt to do so, the following are some key takeaways from the experience.

1) The Importance of Due Diligence

“The best way that independent filmmakers can protect themselves from bad distributors is to do due diligence,” said distribution strategist Peter Broderick. “Due diligence should involve speaking to 3-5 filmmakers who are currently, or recently, in business with that distributor. The filmmaker should not ask the distributor for referrals, they should look up which films the company is working with and have confidential conversations with them about their experience. Is the distributor sending reports regularly and paying on time? Are they easily accessible to their filmmakers? Have the results matched the expectations created by the distributor? If the filmmaker isn’t comfortable sharing numbers, that’s fine. You just need a clear sense of whether working with this distributor is an opportunity or could be a disaster.”

It’s true that if I had done proper due diligence in 2021, when I was considering signing with Passion River, I probably would have avoided disaster. It seems that Passion River had been withholding payments even back then. But we also need some sort of institution where we can centralize our experience and knowledge around distributors. The issue is that everybody exists in their own silo and they don’t speak up out of fear. We need some sort of centralized way to create accountability.

2) The Filmmaker Suffers Most

It’s clear that the filmmakers bore the brunt of this entire fiasco. We were the ones who invested in our films. We are the ones who suffered the financial fallout. The employees at Passion River got new positions at BayView. Josh Levin maintains a faculty position at American University. There’s not much revenue in independent documentaries, and there is a layer of professionals who scrape whatever exists up top, leaving little to nothing for the filmmaker. So be careful where you spend your resources.

3) A Warning of What’s Ahead

The collapse of Passion River happened at an uncertain time for the industry at large. 2023 started off with the Sundance Film Festival, which saw the worst sales of documentaries in years. There will continue to be more disruptions as new technology and viewing habits change the way films are made and seen. This is also happening in a tumultuous macroeconomic environment. I would not be surprised if more distributors start to become insolvent or if they sell off their assets in the same manner Passion River did. In fact, there’s a thread on the Protect Yourself Facebook Group [Facebook account required and one must join the group to view] about filmmakers not getting paid by 1091 Pictures. If you have a contract with a film distributor, be on high alert. Stay on top of payments and reports. Ask the difficult questions. Be vigilant. If Passion River gets away with all of this, it could become a blueprint for other distributors to follow.

Thank you for reading. If you have any questions or comments, please reach out to me at pat@hardrainfilms.com.

admin October 31st, 2023

Posted In: Distribution, DIY, Documentaries, Facebook, Legal

Don’t Just “Take the Plunge” in a Distribution Deal

Part 1: Know What You Are Saying “Yes” To • by Orly Ravid

Part 2: Thank U (4 Nothing), Next • by David Averbach

Part 3: Goals, Goals, Goals • by Orly Ravid and David Averbach — COMING SOON

Part 1: Know What You Are Saying “Yes” To

by Orly Ravid

We know from filmmakers the reasons they often choose all rights distribution deals, even when there is no money up front and no significant distribution or marketing commitment made by the distributor. Regardless of whether the offer includes money up front, or a material distribution/marketing commitment, we think filmmakers should consider the following issues before granting their rights.

The list below is not anything we have not said before, and it’s not exhaustive. It’s also not legal advice (we are not a law firm and do not give legal advice). It is another reminder of what to be mindful of because independent film distribution is in a state of crisis, and we are seeing a lot of filmmakers be harmed by traditional distributors.

Questions to ask, research to do, and pitfalls to avoid

- Is this deal worth doing?: Before spending time, money, and energy on the contract presented to you by the distributor, ask other filmmakers who have recently worked with the distributor if they had a good (or at least a decent) experience. Did the distributor do what it said it would do? Did it timely account to the filmmakers? These threshold questions are key because once a deal is done, rights will have been conveyed. So ask that filmmaker (and also decide for yourself) whether they would have been better served by either just working with an aggregator or doing DIY, rather than having conveyed the rights only to be totally screwed over later.

- Get a Guaranteed Release By Date (not exact date but a “no later than” commitment): If you do not get a “no later than” release commitment, your film may or may not be timely released and, if not, the point of the deal would be undermined.

- Get express specific distribution & marketing commitments and limitations / controls on recoupable expenses: To the extent filmmakers are making the choice to license rights because of certain distribution promises or assumptions about what will happen, all of that should be part of the contract. If expenses are not delineated and/or capped, they could balloon and that will impact any revenues that might otherwise flow to the filmmakers. There is a lot more to say about this including marketing fees (not actual costs, but just fees) and also middlemen and distribution fees. But since we are really not trying to give legal advice, this is more to raise the issues so that filmmakers have an idea of what to think about.

- Getting Rights back if distributor breaches, becomes insolvent, or files for bankruptcy: Again, lots to say about this which we will avoid here, but raising the issue that if one does not have the ability to get their rights back (and their materials back) in case a distributor materially breaches the contract, does not cure it, becomes insolvent, or files for bankruptcy, then filmmakers will be left having their rights tied up without any recourse or access to their due revenues. It’s a horrible situation to be in and is avoidable with the right legal review of the agreement. Of course, technically having rights back and having the delivery materials back does not cancel already done broadcasting, SVOD, AVOD and/or other licensing agreements, nor can one just direct to themselves the revenues from platforms or any licensees of the sales agent or distributor (short of an agreement to that end by the parties and the sub-licensees)…but we will cover what is and is not possible in terms of films on VOD platforms in the next installment of this blog.

- Can you sue in case of material breach? Another issue is, when there is material breach, does the contract allow for a lawsuit to get rights back and/or sums due? Often sales agents and distributors have an arbitration clause which means that the filmmakers have to spend money not only on their lawyer(s) but also on the arbitrator. Again, there is much more to say about this, but we just wanted to raise the issue here. There are legal solutions for this, but distributors also push back on them, which gets us back to the first point, is this deal worth doing? Because if the distributor’s reputation is not great or even just good, and, on top of that, if it will not accommodate reasonable comments (changes) to the distribution deal that would contractually commit the distributor to some basic promises and therefore make the deal worth doing and protect the filmmaker from uncured material breach by the distributor, then why would you do that deal?

Filmmakers too often just sign distribution agreements without understanding what they are signing or without hiring a lawyer who knows distribution well enough to review the agreement. This is foolish because once the contract is signed and the delivery is done, the film is out of the filmmakers’ hands and they will have to live with the deal they made. If that deal was not carefully vetted and negotiated, then the odds are that it will not be good for the filmmaker. Filmmakers can make their own decisions, but we urge them to be informed.

How to best be informed:

- Get a lawyer who knows distribution

- Check out our Case Studies

- Read the Distributor ReportCard to see what other filmmakers have said about a distributor and/or find filmmakers to talk to on your own who have used them recently. If we haven’t covered a certain distributor in the DRC but one of our films has used them, just contact us. We could be happy to ask them if they’d be willing to speak with you, and, if so, make an introduction.

Part 2: Thank U (4 Nothing), Next

By David Averbach

When TFC started our digital aggregation program[1] in 2012, there was a palpable sense of possibility, that things were changing–access was opening up, and filmmakers were finally being given a more even playing field. Who needed middlemen when one could go direct [2]!?

In many ways, going direct, choosing to self-distribute, was (and maybe still is) viewed a bit like electing to be single, as opposed to the “security” of a relationship and/or a marriage. When your film gets distribution, it’s a little bit like, “They said, ‘yes!’ Somebody loves me. I don’t have to go it alone.” Less stigma, more legitimacy.

Relationships and distribution deals have a lot in common. If you are breaking up with your distributor, it can get messy. That’s why TFC Founder Orly Ravid has outlined above some of the basic concepts and things you can do with your lawyer to make sure that if you choose to do a deal, you protect yourself as you enter into a binding relationship. Like a pre-nup. So that you get to keep everything you brought with you into said relationship when you part ways.

Good News, Bad News

So, let’s say there is good news in the sense that you are able to hang on to whatever belongings you brought into the relationship.

But there’s bad news, too. Your ex is keeping all the stuff you bought together.

At least it’s going to feel like that. I know…you would rather kick your ex out and stay in your apartment. Really, I get it. But it’s not going to happen. It’s going to feel like your ex has all your stuff and won’t give it back. Because you are not going to feel grateful like Ariana; you will want someone to blame. But that’s not really fair. Because it’s more like you are both getting kicked out of the apartment and technically your partner still owns all the stuff that’s still inside, but also that they changed the locks and neither one of you can get back inside and access it. And, also, you are now homeless. Good times.

OK, let’s back up for anyone confused by the breakup metaphor: You got the rights to your film back.[3] Yay! Your film is up on all these platforms. All you want to do is keep it up on those platforms. Sorry, not gonna happen. You’re going to have to start again from scratch.

Why you have to start from scratch with most platforms when you get your rights back.

I know, you have questions. From a common-sense perspective, it makes zero sense. I’m going to go through the reasons as to why this is the case, on a sort of granular, platform-focused basis, but the answers I think say a lot about how the distribution industry is and, in many ways, has always been set up. And it underscores everything I’ve always suspected about the sorry state of independent film distribution.

I have to thank Tristan Gregson, an associate producer and an aggregation expert of many years, who was generous enough with his time to rerun questions that filmmakers have asked him over the years about salvaging an existing distribution strategy, and why, unfortunately, it is pretty much impossible.

So, let’s begin by limiting our parameters. I mentioned shared materials that were created after your deal was signed. If your distributor created trailers and artwork, I suppose that technically they own the rights, even though your distributor probably recouped their cost, but the train has left the station on those, so how likely is it that someone would go after you for continuing to use them? I would recommend making sure you have a copy of the ProRes file for your trailer and layered Photoshop files (along with fonts and linked files) or InDesign packages for your posters before things go south, because you are going to need the originals again when you start over. I’m assuming you still possess the master to your actual feature. And don’t forget about your closed captioning files.

Licensing deals (that ones that come with licensing fees) have been harder to come by for many years, but if your distributor has licensed your film to a platform, the license itself would be unaffected, so that would not have to be “recreated,” so to speak.

The rest—the usual suspects: transactional platforms (TVOD), rev-share based subscription platforms (SVOD), and ad-supported platforms (AVOD) (in other words, situations where revenue is earned only when the film is watched)—are what I’m going to be focusing on here.

Let’s say your film is up on a handful of TVOD and/or AVOD platforms. Why is it not possible for them to remain up on those platforms?

In the best of all possible worlds, couldn’t somebody simply flip a switch, change some codes, and point all the pages where your film currently lives to a new legal entity and let you continue on your merry distribution way?

But who exactly is this “someone”? They would have to have a direct contact at the platform. So maybe that’s your distributor, maybe it’s their aggregator. And is this contact at the platform the person who will do this? Probably not. It’s probably someone who deals with the tech. So now, you need to mobilize a small army of hypothetical people who are all willing to do this work for you for free. For each platform that you’re on. And don’t forget things between you and your distributor are complicated and tense right now. They are going to do you a favor to save you a few thousand bucks?

But it’s actually worse than that. You would also be assuming that Platform X, who perhaps is also trying to sell books, goods, phones and tablets, actually cares one single iota about your tiny (but fantastic) little film enough to do this for you. They do not. Despite happily taking 30-50% of your selling price for all these years. They absolutely do not.

The Nitty Gritty

I had suspected this, but I sought out Tristan for confirmation. I had only spoken previously to Tristan on a handful occasions, but he is an affable guy. Gregarious but not to the point of being garrulous. He cares. Talking to him, you get the feeling that he would go the extra mile for you if he could. Please remember this as he recites answers that he has probably given more times than he can count. His cynicism is well earned…it comes from experience.

[Note: I’ll ask and answer some of my own questions in places. Tristan’s responses will be in italics, mine will be in plain font.]

You are my distributor’s aggregator. Can’t I just work with you directly?

The answer is yes, if you start from scratch. But your distributor paid for the initial services. They paid to have it placed there. Not you.

But I made the film, and I got my rights back. Why can’t you tell Platform X to keep it up there and just change where the money should go?

Yes. I know your name is listed. But that string of 1s and 0s is associated with your distributor, not you.

It all comes back to tech. Because at the end of the day, it’s a string of 1’s and 0’s that are associated with a media file. It’s not your movie in a storefront or on a digital shelf or anything like that. In the encoding facility/aggregator world, these 1’s and 0’s are the safety net for us. We have an agreement with Party X. If Party X ends the relationship or ceases to exist, it’s written into that agreement that we pull everything down—we kill it from our archives. We’re protecting everyone. We don’t want to hold onto assets that we don’t have any relationship with. Those strings of 1’s and 0’s that go up onto a platform, and that platform has an ID tag that’s tied with the back end of the system, and that system reconciles the accounting, and the accounting reconciles with the payout. We can’t go in and just change a name on a list. That’s just not how that works.

You (the independent filmmaker with a movie) do not have a relationship, direct or indirect, with any of the platforms your distributor placed your title onto. As such, your title would not continue to be hosted at any of these outlets should your relationship with your distributor officially end. People often would say “it’s my movie, now that Distributor X is gone, just have the checks go to me.” That’s not how the platform or the aggregator ever see it, which I know is very painful for the creator who may now think they control “all their rights.”

It’s just a business entity change.

Aren’t you going to be sending me a new file anyway? Isn’t the producer card or logo going to change at the beginning the film? That’s gotta be QC’d again, in any event.

Are you telling me that if I had a 100-film catalogue, I’d have to re-QC 100 titles from scratch? That’s insane.

Let’s say Beta Max Unlimited Films had 100 titles with us and then, Robinhood Films, who is also a client of ours comes along and says, ‘Hey, we bought Beta Max Unlimited Film’s catalog, we bought all the rights to all of it. Work with us to move it over. All you guys have to do is do it on the accounting end.’ Let’s say we would be willing to do it. And let’s say we contact Platform X, we were to talk to them, talk to our rep there, and they say they are willing to relink all that media on their end, they’ll move the 1’s and 0’s over. Even then, 99 times out of 100, it never happens because you’ve got a bunch of people, and these people are kind of working pro bono on something that doesn’t really matter to them.

Just because you may think something is easy or “no work at all” doesn’t make it true, and even when it is, nobody wants to work for free. Something may be technically possible, but having all the different parties communicate and execute just never happens when nobody’s directly being paid to do the actual work.

Are you kidding me? Platform X wouldn’t move a mountain for a hundred titles?

Like, that’s nothing to them, it means nothing. What matters to them—is that stuff plays seamlessly, and it has been QC’d and approved and published. They don’t need to deviate from this because at the end of the day, it’s not going to help sell tablets and phones.

And again, we’re talking about multiple platforms. What happens if they could do this… and they get 6 out of 8 platforms to comply but the other two are intransigent? They’re going to come back to you and say, “Sorry, we tried. We hounded them 16 times, but these two won’t do it. And now you have to pay anyway to redeliver if you want to be on these two platforms.” You are going to think the aggregator is scamming you. It will not be a good look for them. Why would they want to agree to work for free with the likelihood that they will end up looking bad in the end? KISS (Keep it simple, stupid). It only makes sense to ask you to start from scratch.

Are there platforms I can actually go direct with?

You can do Vimeo On Demand on your own. (Note that for top earners [top 1%], there may be an extra bandwidth charge. You can read more about that here).

You can also do Amazon’s Prime Video Direct.

Altavod, Filmdoo, Popflick…More on these later.

I thought Amazon wasn’t taking documentaries?

I believe that’s still true? However, I have access to a small distributor’s Amazon Video Direct portal. In 2021, there was a big, visible callout that said something to the effect of, “Prime Video Direct doesn’t accept unsolicited licensing submissions for content with the ‘Included with Prime’ (SVOD) offer type. Prime Video Direct will continue to help rights holders offer fictional titles for rent/buy (TVOD) through Prime Video. At this time Amazon Prime does not accept short films or documentaries.” This is June 2023. I cannot find this language anywhere in the portal. But I believe that is still the case.

What about “Amazon Prime” SVOD?

In the portal, all the territories that were once available for SVOD are still “listed,” it’s just that the SVOD column whereby you could check each one off is gone. So, no SVOD for unsolicited fiction. If you create your own Amazon Video Direct account, the territories that are available in an aggregator’s account might differ from an individual filmmaker’s account. All this seems to be moot if SVOD is not available.

So, for Amazon, it’s only TVOD?

Yes.

[Sidebar: It has usually just been US, UK, Germany, and Japan. Amazon just announced Mexico, but for this option to be available in your portal, one needs to click a unique token link that was sent out. The account I have access to received this notification. I am not certain whether this link was or will be sent out to all users. Localization is required for the non-English speaking territories in this category.]

But my distributor had gotten my documentary onto Amazon. If I have to start from scratch with my own account, is there a way to convince them to once again allow it in?

Best of luck with that. Amazon is notoriously difficult and unresponsive, even with aggregators. You can try, and even if it is initially rejected, there is an appeal link somewhere in the portal that you can write in to. I have no idea if that will do any good.

My film was Amazon Prime SVOD. If I have to start from scratch with my own account, is there a way to convince them to keep it in there?

“Keeping it” is not the most accurate way of looking at the situation. It’s basically going to create a new page. And that will be controlled by the back-end in your personal account. SVOD will probably not be an option in this account. You can write in, as mentioned above, but it seems as though Amazon is trying to lessen the content glut for its Prime Video service, so I have my doubts as to whether very many people who make this request prevail.

Wait…what??! You mean that I will have a new page and therefore will lose all my reviews?

Yes and no. The old page and reviews might still be there, but “currently unavailable” to rent or buy. But on your page, the page where it is available, the reviews will not carry over. Reviews not carrying over is probably true for all platforms, but Amazon reviews are more prominent than on other platforms, so they are usually what filmmakers care about the most.

My distributor had gotten my film onto AVOD platforms Tubi / Roku / Pluto TV, etc. Do I have a better chance of getting my “pitch” accepted because it was on there before?

No.

But why? It was making some pretty good money.

You are assuming that the Tubi / Roku / Pluto TV, etc. acquisitions person is the same person who approved your film in the first place, and even then, they are going to remember your film, or are going to take the time to look up your film and see how it was doing, and also that amount of earnings you may have gotten is going to mean enough to them to matter.

If I somehow could convince someone to keep assets in place, there’s no downside, right?

Actually, that may not be true. It’s about media files meeting technical requirements, which change over time. What was acceptable yesterday isn’t always acceptable today. So when you attempt to change anything at the platform level, you risk removal of those assets already hosted on a platform.

OK, I think you get the point.

Tristan reminded me that you need to think of yourself as a cog in the tech machine.

You think all this is too cynical? Think about it…

It’s always been that way, even though we never wanted to believe it. Take the Amazon Film Festival Stars program circa 2016 as an example. A guaranteed MG. Sounded great. But on a consumer-facing level, did they make any attempt to create a section on their site/platform where discovery of these purported gems could take place? No. Did you ever stop to ask yourself why? Because at the end of the day, they didn’t really care. Any extra money they would have made was so insignificant to them that it was not worth the effort. So, they discontinued the program and blamed lack of interest.

To be fair, iTunes for many years had a very selective area for the independent genre. But it’s gone/hidden/trash now with AppleTV+. They would rather peddle their own wares than create a section that champions festival films. And remember that one, poor guy who I shall not name that you had to write to and beg in order to get your film even considered for any given Tuesday’s release? Even if you were lucky enough to be selected, if your film didn’t perform well enough it would be gone from that section by Friday morning. Or by Tuesday of the following week. All that seems to be gone now. Independent films don’t make money for them. Even though they are willing to spend $25M on CODA and $15M on Cha Cha Real Smooth.

And every so often, new platforms (like Altavod, Filmdoo, Popflick) emerge that want to change this. There are films that you actually recognize, that have played in festivals alongside yours…just…listed all together! But, have you heard of these platforms, let alone rented a film off one of them platforms or paid a monthly subscription fee? Chances are you haven’t.

This is not to blame you. But by all means, check these mom-and-pop platforms out and support your fellow filmmakers. And these are not the type of platforms that would be so hard to re-deliver to anyway. They’d probably be happy to go direct with you. It’s the big platforms that are calling cards, the ones that everyone uses, that you will want to be on even if you secretly know they are not bringing in much in terms of revenue. But either way, these platforms don’t care.

Let’s remember why aggregators exist. It’s because platforms don’t care, couldn’t be bothered, and waived their magic wand over some labs out there and said, “Now you deal with them. You be the gatekeepers.” And a whole business sector was created.

There are some distributors out there who have been around for a while that may very well have contacts at some of these platforms, but it doesn’t matter. You don’t have those connections, and chances are that they are drying up for these distributors, too.

And while this is crushing, it might also be freeing.

Tristan echoed what TFC has been saying for years: You are your own app, your own thing, most importantly, your own social media marketing campaign.

If you think about getting into bed with a distributor being like a relationship or a marriage, then your film is the kid you are raising. What kind of parent is your distributor? What kind of parent are you? Your distributor might say they will do marketing (change the dirty diapers), and then do it once or twice, but then they don’t do it again. Who is going to change those diapers it if it’s not you?

So, this relationship metaphor I am positing should not solely be directed at filmmakers who are getting their rights back. When you enter into a deal with a distributor, some filmmakers think they can now be deadbeat parents, when in reality you should co-parenting. And when your relationship with your distributor ends, you still need to raise the kid, right? It’s all on you now. And the truth is, it always was.

Notes:

[1] TFC discontinued our flat-fee digital distribution/aggregation program in 2017. [RETURN TO TOP]

[2] When we say “direct,” we mean direct to a platform, or semi-direct through an aggregator that doesn’t have a real financial stake in your distribution, as opposed to a distributor that takes rights and is (or purports to be) a true partner in your film’s distribution strategy. [RETURN TO TOP]

[3] It’s important to ensure that you have your rights back. Easiest and best way is to ask your lawyer and go through it with them both in terms of your distribution agreement, but also on a platform by platform basis. Also, to the extent that you will need to start from scratch, make sure your distributor’s assets on each platform have been removed or disabled before you attempt to redeliver them to each platform. [RETURN TO TOP]

Part 3: Goals, Goals, Goals

By Orly Ravid and David Averbach

Coming soon

admin June 8th, 2023

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distributor ReportCard, DIY, education, Legal

All About AVOD? part 1: What To Do with Your Library Title

by David Averbach and Orly Ravid

One of the joys of working at The Film Collaborative is our extended filmmaker family. Some of the filmmakers we work with we have known for decades, back to when they made their first films. Inevitably, after seven-, ten-, or twelve-year terms, many of these filmmakers are getting their rights back from the distributors with whom they originally entered distribution deals.

They often ask us, “What is possible for my film now? What can I do to give it a second life?”

(We should state that the vast majority of these filmmakers do not have obviously commercial projects that could simply be offered to a different large streaming service like Netflix or Hulu. They are the type of films that TFC handles: solid films with good or at least decent festival pedigrees and proper distribution at the time of their initial release.)

Unfortunately, there is no one answer for every film. Nor is there a fixed answer for each type of film, as platforms’ needs can change at the drop of a hat. Except that all platforms seem to have an endless appetite for true crime docs, but we digress…

So, this blog article is less of a “how to” for library titles, and more of a “how to think” about them.

Certainly, there are non-exclusive subscription-based (SVOD) platforms that align with various content areas, such as Documentary+, Topic, Wondrium, Curiosity Stream, Coda, Qello, Tastemade, Gaia, Revry, and many more (check out our Digital Distribution Guide for more info). These are platforms that offer a revenue share based on minutes watched. Since they may have not been in existence when the filmmakers’ original distribution deals were arranged, they are definitely worth exploring when one (or more) of them is a fit for your project.

But there are also ad-supported (AVOD) platforms1, which are free to the end user and rely on commercials that play before the film starts. Generally speaking, AVOD platforms seem to be more lucrative in terms of revenue than specialized SVOD platforms, and we’ve heard that some films are making “real” money them (more on that later). While there’s no guarantee that AVOD platforms will bring in more money than SVOD platforms, or much money at all, this at least makes sense, anecdotally: with the rise in commercial streaming services and especially since the start of the pandemic, folks are watching increasingly more content, but actually spending less above and beyond the Netflix/Amazon Prime/HBO/Disney etc. combination of platforms that they have ostensibly come to view as basic utilities.2 So AVOD provides a win-win for platforms and consumers alike.

Until recently, filmmakers have been somewhat reluctant to place their films on AVOD platforms, but they are coming to realize what distributors have known for a few years now—that AVOD can continue to bring in revenue when transactional platforms such as iTunes are no longer performing for a film the way they might have at the beginning of their digital run.

So, we set out to ask what we believed was a simple question: which AVOD platforms are taking which type of library content? The Film Collaborative has some limited experience with AVOD platforms, but we felt it prudent to talk to some folks that do this day in and day out. To that end, we reached out to Nick Savva, Vice President of Content Distribution at Giant Pictures, and Tristan Gregson, Director of Licensing & Distribution at BitMAX.

The answer turns out to be a complicated one. Here’s why:

Most AVOD platforms are looking for all kinds of content. One of the trends that has been occurring for the past few years is the addition of new platforms, not just in the U.S., but globally. And the pandemic has accelerated existing trends, so there are even more new platforms than ever. These platforms are not going to be able to produce or acquire enough new content to justify their existence, so they rely on library titles as much as they do new releases. So, the good news is that there are more outlets and revenue opportunities for library titles than ever.

The not-so-great news is that sometimes AVOD platforms are actually looking for specific types of films, but only for a limited time to fill a specific need. Platforms have a good sense of what percentage of their films are, for example, comedies, dramas, thrillers, horror, documentaries, true crime, etc. When they look at who is watching what, if comedies are overperforming on the platform relative to the percentage of titles they occupy overall, the platform may not take as many comedies for a while until that changes, or they could decide to double down and take more comedies at the expense of other types of films. Conversely, if there is a category that is underperforming, they could decide that they need some fresh meat in that category, or simply decide to take less of it.3

So why exactly is this bad news? Because as the needs of AVOD platforms ebb and flow, the entities with the best chance of succeeding are those that can respond quickly to calls from these platforms for specific content. A high percentage of the work Giant Pictures does with AVOD platforms involves their distributor clients, who use Giant as a sort of white label service. Giant is tasked with placing their content libraries on these platforms because these distributors don’t have the bandwidth to keep up with which platforms want what from month to month. Similarly, BitMAX works with many studios to deliver to these platforms, but the studios are the ones handling the licensing. What this means is that the bulk of content going to AVOD platforms is coming from the content libraries of studios and distributors. That is not to say that films from individual filmmakers aren’t being placed on AVOD platforms by Giant/BitMAX, it’s just that studios and distributors are their go-to sources for content because they can provide a bunch of titles with a quick turnaround.

The sad reality here is that AVOD is one area of distribution where middlemen are being added to the mix in a way that makes it harder for individual filmmakers to take back control of their films.

Many of the filmmakers who have just gotten their rights back often remark to us how glad they are to have done so, as if they are finally getting out of a bad marriage. Even if the relationship wasn’t such a badmarriage, this sentiment—justified or not—perhaps stems from the fact that their TVOD sales had dropped over the years and they felt like their distributor was no longer doing anything for their film, or that they were tired of not receiving reporting because there were long periods of time with no earnings. The last thing they appear to want to do is start up a new relationship with a new distributor or aggregator and incur more encoding costs for a shot in the dark in terms of being accepted by these platforms only to earn $12 a quarter in earnings.

It’s important to really have a look at the reporting your old distributor provided you. There’s a good chance that simply re-creating what your old distributor did—perhaps your film was already on AVOD platforms—is going to give you a completely different outcome. But to the extent that your project has not been tested in the current landscape, what should a filmmaker be thinking about if they find themselves in the position of deciding whether to go it alone or offer their film to another distributor?

It’s Your Time and Money

Bandwidth:

Tristan Gregson remarked that the same rules apply for library titles as when just starting out, and his stance was the following: if you know how to engage your audience then put it somewhere. If not, then don’t. Whether you try to go it on your own or partner with another distributor, unless there is someone that’s going to remind your audience that it’s there, there’s a good chance your film will sit unnoticed in a glut of content. This is going to take some effort and while a new distributor might do a bit of marketing, you are going to have to get creative. Perhaps time the re-release of this older film with a new project of yours?

Cost:

If you go through an aggregator like BitMAX, you are probably looking at a bare minimum of $2,000 for encoding, QC, and delivery and to pitch and deliver to a few SVOD or AVOD platforms. It’s a fee for service, so they will be hands off when it comes to strategy, and uninvolved when it comes to your earnings. If a distributor like Giant Pictures is willing to work with you, it can cost twice that much, but they will be real partners in the sense that they will be proactive in helping you come up with a strategy. They will also take a certain percentage of your earnings. You may also be able to negotiate lower encoding costs in exchange for an increased percentage of your earnings.

What is in it for the Platform?

Metrics:

Nick Savva advises filmmakers to think about your film like a platform would: what are your film’s metrics? These scores can tell a lot about the public’s level of familiarity with your film, and there are data tracking services that distributors and platforms use to determine them. Also among the first things that an acquisitions team would look at would be indications of basic audience awareness, such as the of the number of positive reviews on Amazon, or the ratings on IMDb. If the metrics are good, a deal might be attractive to a platform. Are there any recent reviews? In other words, does your film still hold up?

Is there one Platform that is better for my film than others?

Honestly, there are not all that many AVOD platforms in the U.S. Tubi, Pluto, Roku, Peacock, IMDb TV, and a few others. The good thing about AVOD is that most deals are non-exclusive, meaning that you can be on more than one at once. But should you apply for all of them? How does one decide?

Signal Boost:

The following might not be possible for every film, but, if possible, try to think about the likely television habits of your audience and the specifics of each platform and take advantage of the free signal boost.

People are very familiar with platforms like Netflix and Hulu, but when it comes to platforms like Tubi or Pluto, why would one choose to watch one over the other? The answer might be simpler than you would think!

Does your film have a TV star in it? If they are on the FOX network, chances are that audiences will see ads for Tubi, because Fox is the parent company of Tubi. If they are on NBC, then perhaps Peacock or Xumo will be advertised.

There are also tricks that might apply for documentaries too. Pluto just became available in Latin America and Mexico, so films with Latinx content might want to consider that platform first.

One of The Film Collaborative’s digital distribution titles, The Green Girl, has been doing extremely well on Pluto, but not so well on Tubi or Roku, and for the longest time we couldn’t figure out why. Then it hit us: this documentary is about an actress who famously appeared on the 1960s television show Star Trek. Since Pluto is owned by Viacom, which is the parent company of Paramount, Pluto is the AVOD destination platform for Trekkies!

Keywords:

Make sure your keyword game is strong. Aggregators and distributors will ask you to fill out a metadata sheet with genres/keywords, but you must make sure the choices conform to actual categories and genres on the platforms, which can differ from one another and evolve over time. Distributors have even admitted that it’s hard for them to keep up sometimes, especially if such metadata is capture via web interface. Case in point: The Film Collaborative placed a few films we have been working with for years onto Tubi, but the keywords that we chose when we first submitted the film to our aggregator were based on iTunes genres, which are very narrow. Cut to the films getting up onto Tubi, and they were almost impossible to find without searching for their exact titles. It’s been several months, and we are still struggling, with the help of our aggregator, to get these updated on the platform. Bottom line is that it’s important to be familiar with each platform and know how one might best search for your film and be proactive to ensure that the proper information is being delivered to each platform at the time of delivery.

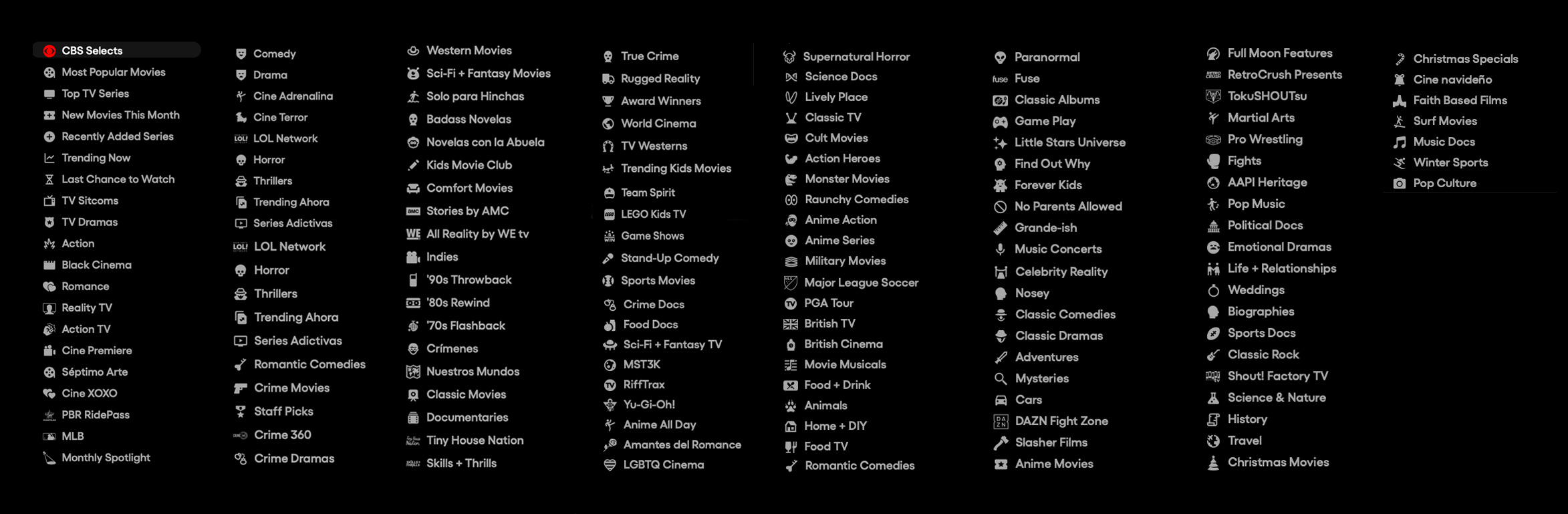

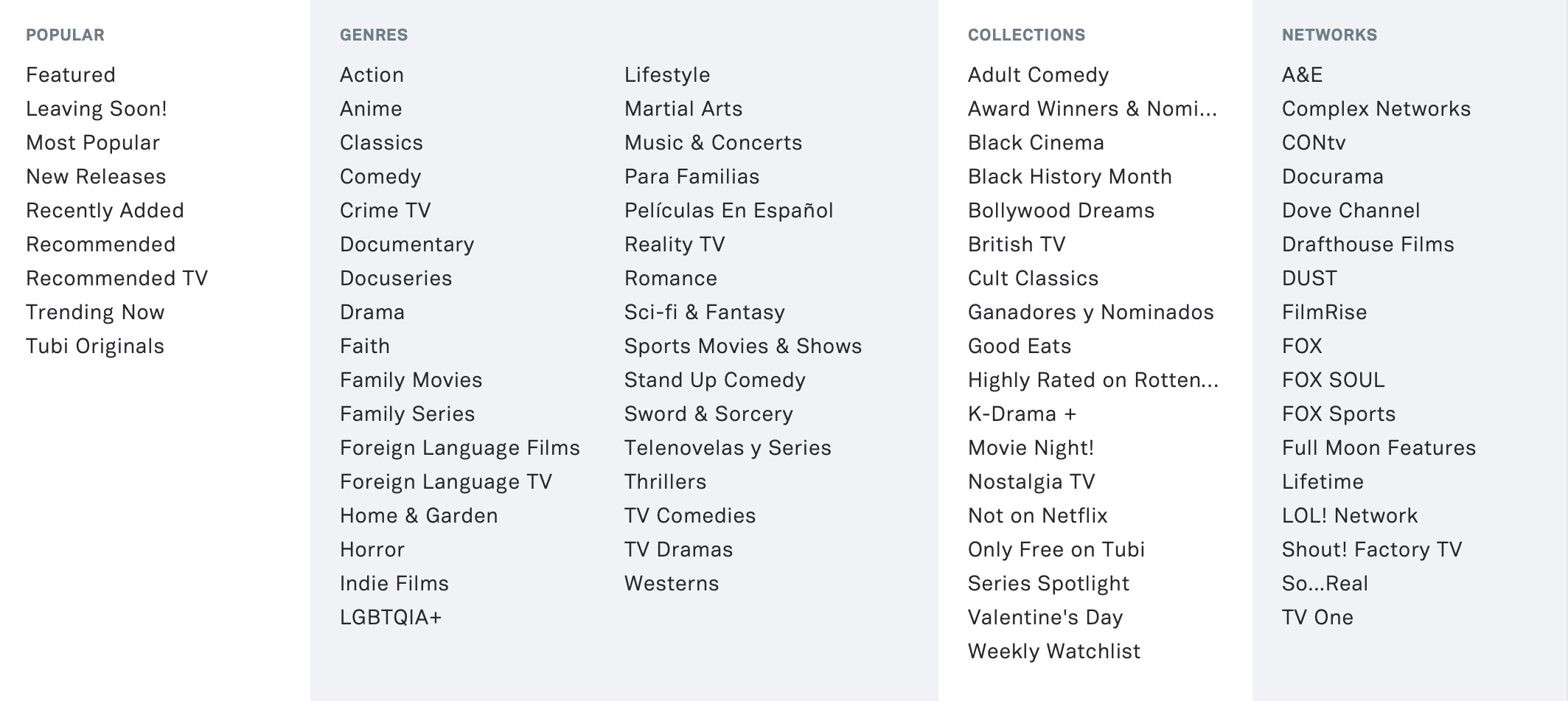

Pluto TV (owned by CBS/Viacom) offers a dizzying array of genres/categories to choose from (they appear in a vertical sidebar and seem to rearrange themselves periodically)

Tubi’s current “Browse” navigation tab. Tubi’s parent company is Fox Corporation.

Very Mini Library Titles Case Study

We talked to director/producer Kim Furst, whose rights to her 2014 film Flying the Feathered Edge: The Bob Hoover Project came back to her after her aggregator (Juice) declined to renew the term. She expressed that she did not want to use another aggregator like Distribber/Quiver/Bitmax/FilmHub because there was a concern that they might not be around in another 5 years. (As you probably are aware, Distribber has shuttered, and Quiver is not currently accepting films from individual filmmakers and will probably turn into something else).

So, she went with Giant Pictures.

The cost to re-encode was about $4K. While she did not feel great about having to shell out such a huge chunk of cash on a library title, Kim still felt that the film still had life in it, and she wanted to try other distribution avenues, such as public television, that she never managed to do when the film originally came out.

We should note that one of the reasons why Giant might have been interested in the film was that it is narrated by Harrison Ford. The film is about Bob Hoover, an American fighter pilot and air show aviator, and Ford has a longstanding love of flying planes. So, there is some commercial appeal that can be leveraged here.

She is at the stage where they have initiated the re-release. Right now, the film is back up on TVOD platforms, including being re-placed on Amazon, which Giant was able to accomplish despite the platform’s embargo on unsolicited non-fiction content.

We asked Kim to report back on what happens next. We suggested that she note where all of Harrison Ford’s top movies are on AVOD and take note if that platform sees any boost from the connection.

Revenue Range

With so many variables and permutations, it’s hard to give a real range in terms of what’s possible for a library title on AVOD, especially since it’s impossible to know when we are talking about the revenue of a “library” title—as opposed to that of a title that enters AVOD as part of their “new release” window.

When I asked Tristan about revenue, he acknowledged that to even talk about it would put us into “anecdotal space,” because he isn’t aware of what it took for some of his clients to earn, for example, 5 figures during an AVOD revenue period, as compared with other clients who were only able to earn, say, 3 figures. While he admitted that he has seen a single independent film title clear quite a bit, he also reiterated to me that at a certain point of revenue generation, distributors tend to get involved with a title to signal boost, so it isn’t exactly “a fair comparison to those independents working day in and day out to make a few grand on their title. But if the message is that you don’t have to be working with one of the major studios to reach seven figures in revenue, it can still very much be accomplished in this current age of VOD releasing.”

Nick spoke more specifically to AVOD, noting that they “have had a couple of indie titles which have generated $100k+ royalties in 1 month on 1 AVOD platform. But, of course, those are outliers.”

One of our filmmakers told us that they have two filmmaker friends-of-friends (whose films deal with Black Cinema content) for whom Tubi is paying well: one reported $15K a month in residuals while the other one says they are making $4-6K a month on a movie released 10 years ago. Both filmmakers allegedly went through an aggregator, but their friend said they were reluctant to allow the names of their respective films to be shared publicly.

So, as Tristan remarked, it’s best not to hold too tightly onto evidence that is merely anecdotal, because TFC certainly knows films that are making almost nothing on AVOD.

Notes:

1. As we were conceiving this article on Library titles, and realizing how important AVOD could be for an older title, Tiffany Pritchard of Filmmaker Magazine approached us about an article she and Scott Macaulay were writing about AVOD. Its title is Commercial Breaks and it is available in the January 2022 issue of the magazine (behind paywall, at least for now).

2. As a reference, this article discusses how shorter theatrical windows might be accelerating TVOD decline and shows the increase in both spending and subscription stream share from 2019 to 2021. Others, however, predict that streaming services will lose a lot of subscribers in 2022. Still, it’s hard to know how streaming services are faring, as many of them are not transparent in their total number of subscribers and average revenue per year.

3. Stephen Follows assembled a team, called VOD Clickstream, that uses clickstream data to analyze viewing patterns on Netflix between January 2016 and June 2019. He also offers a ton of information on his website. In November 2020, he presented a talk entitled, “Calculating What Types of Film and TV Content Perform Best on SVOD?”, in which he outlined how he believed Netflix navigates how popular a genre is versus what percentage of content of that genre is available on the platform.

David Averbach February 8th, 2022

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms, DIY, Documentaries, technology

Spotlight on Indie Film Platform FilmDoo

by Orly Ravid.

by Orly Ravid.

I was introduced to indie film platform FilmDoo.com and decided to share it with you all here by asking FilmDoo some questions. I spoke to Weerada Sucharitkul, CEO & Co-Founder and most of what is below are Weerada’s own words in response to my questions.

What is FilmDoo’s Mission?

We help people to discover and watch great films from around the world, including documentaries and shorts. Essentially, we help people discover non-Hollywood films, which include independent films from the US and UK, as well as mainstream blockbuster films from China and Japan, for example. We not only help people to discover films but languages and regions, and are very much a ‘TripAdvisor for Films.’ On FilmDoo, you can discover films from Africa, Asia, Latin America and Europe, many of which we are the first to show internationally outside of film festivals. Furthermore, we also have a very engaged global film community (users can have an active social profile and leave reviews, comments as well as engage with other community members) and are an extensive international film database source, which is increasingly becoming an alternative to IMDB for foreign language films. As such, we are not only a VOD platform, we are more than that—a global database of foreign films as well as rapidly growing international community of film fans.

How does the platform work? What is FilmDoo’s Business Model?

FilmDoo’s current model is TVOD (pay-per-view) for feature films on the main FilmDoo site. We are a global online streaming platform and have the ability to sell and show films anywhere in the world. We are at over 500,000 visitors a month, with users from 194 countries. As we are increasingly getting a lot of traffic from emerging countries (e.g. Indonesia is now our second biggest traffic country, and countries like Turkey, India, Malaysia and Philippines make our Top 10 list), we are now looking at more ways to further monetize from these parts of the world and could be looking to do an AVOD model in these countries in the near future. We are able to geo-block for any country combination, and only require one month notice from filmmakers or content owners if they would like to change the geo-block country combination. We are able to accept transactions in UK Pound, US Dollar, Australian Dollar and Euro, as well as Paypal and AliPay (for Chinese-based users).

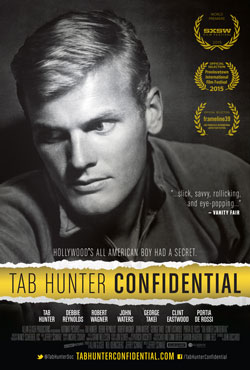

Which types of films do best on your platform?

Search ’gay movies’ and ’lesbian movies,’ and you will see we rank very high on Google from a SEO perspective. At the moment, their best selling category is LGBT films. FilmDoo claims to already have one of the biggest LGBT online film collections in the world. In terms of typical demographics, the audience base is a lot younger than typical ‘world cinema’ audience. They tend to be globally mobile, active on social media, speak many languages and/or learning languages, and come from an international or expatriate background (such as second generation French or Italian). Human rights documentaries have also tended to do well. As such, we see strong appeal for films that fit our current demographics: average age 22-39, young, learning languages, loves travelling and enjoys watching coming-of-age movies, first love movies, thriller movies, road movies, LGBT movies and human rights and social issues.

Where do most of your consumers live? Explain which countries.

Our current Top 10 countries by traffic, in order, include: 1. US, 2. Indonesia, 3. Turkey, 4. UK, 5. Turkey, 6. Malaysia, 7. Philippines, 8. Egypt, 9. Germany, and 10. Saudi Arabia. However, in terms of sales, our top selling countries include: US, UK, Canada, Australia, France, Germany, Ireland, Norway, Netherlands and India. As you can appreciate, given the global nature of our traffic, for many in emerging countries in Asia and Africa, for example, the current TVOD price point is either too high for them, they do not have credit card or they are more used to an AVOD or free viewing model and not used to making transactions online. Hence why we are now exploring AVOD as an option to do more in the rest of the world.

What is the revenue split? Are there any costs recouped?

Revenue share is 70/30, same as iTunes. There are no costs to put the films on the FilmDoo platform, no further additional transcoding or ingestion costs. There are no marketing costs recouped either. The mission is to make it as easily and as flexible as possible for film makers to be able to put their films online at no additional costs and with maximum ease to be able to maximize their full global potential.

Some of their top selling content partners are LGBT content partners who have a collection of films with us and are able to make a decent sum month (I was asked not to share the exact sum publicly).” They note doing increasingly better for other film genres and collections. Launched in 2015, FilmDoo claims to be growing rapidly and expects to grow its catalog and audience.

Please speak to the simplicity, ease, and flexibility of the platform as far as geo-blocking, limiting territories, and the simple delivery, non-exclusivity…

Simplicity, ease and flexibility are absolutely at the heart of what we do at FilmDoo. Our goal is to reduce current barriers to international distribution in the film industry and most of all, to help films, especially films that have had their festival runs and may have already sold in a few territories, to continue to be able to monetize and reach their full global potential. That’s why we want to make it as easy as possible for them.

This includes:

- Ability to geo-block to any country combination requirement, with only one month notice required if you need to make changes to this. We will be able to sell your film in any country.

- We will try our best to work with your material—we can take both HD and SD files (where HD is not available), AppleProRes and H.264. We can accept the digital files via our FTP, WeTransfer, Aspera as well as any other way.

- We can also accept film files sent to us in hard drives by post.

- Where the films are not available digitally, we will also accept DVD/ Blurays and will digitize these at no additional costs to the film makers.

- We do require that all films have English subtitles. If available, it would also help to have native language caption files as separate files (e.g. English captions for English language films, French caption for French language films, etc), although this is not required.

- Our preference is for clean film files with separate subtitle files in .SRT or .WebDTT format.

- However, if separate subtitles are not available, we can also accept film files with burnt in English subtitles.

What is FilmDoo’s Term?

Our terms are 2 years non-exclusive.

As you will see, we are much more flexible and easier to work with than most other global platforms, because our number one goal is to make it as easy as possible for film makers and content owners to put their films online and reach their global audience.

Are filmmakers able to see the data of where their audiences live (country) and how many transactions per each country? Is there a dashboard?

Yes, we have an online reporting dashboard. Film makers or content owners will be able to log in any time to see their total sales in real time. They will be able to see where the sales are coming from, the countries their films are getting the most interest in, and where available, the demographics breakdown of people interested in their films such as gender and age.

Can filmmakers contract with you directly?

Absolutely, please feel free to email me directly at wps@filmdoo.com. In addition, we can also be contacted at our general email: info@filmdoo.com. Please also feel free to follow our news, film releases and reach out to us on our social media: Facebook • Twitter • YouTube.

What is FilmDoo doing to increase its consumer/audience reach?

Through our proprietary marketing technology, we are doing very well on SEO, where we are able to reach global audience interested in Lesbian and Gay movies as well as films by language collection. Furthermore, our proprietary technology include our personalized film recommendation engine.