TFC’s Distribution Days is upon us!

Next week, The Film Collaborative is holding a free virtual distribution conference, Distribution Days, which will offer concrete takeaways on the state of indie distribution and how filmmakers can navigate it. Attendees will hear from exhibitors, distributors, consultants, and filmmakers, some with case studies, as they describe and reflect on the landscape.

This conference hopes to help filmmakers develop critical thinking skills around distribution by looking at what is and what is not viable within a traditional distribution framework. It will also offer some alternative approaches. Willful blindness or a doomsday mindset are equally unproductive.

So, we are offering this pre-conference primer to set the tone, take stock of what myths are out there, and talk about what thought leaders in this space are coming up with as ways to deal with the current landscape.

Here we go!

Remember the days when creators and distributors were lying back in their easy chairs, proclaiming their satisfaction with how independent cinema has been evaluated by the marketplace? Yeah, we don’t either…and we’ve been in the industry (in the U.S.) for more than two decades. Nevertheless, there is a pervading sense that the state of independent film has never been worse—and that we’ve been going downhill from this mythic “better place” ever since Sundance was founded in 1978.

Why do we insist on bemoaning a Paradise Lost when the truth is that being a filmmaker has never been a paradise? Filmmakers have always been confronted with predatory distributors, dense and confusing contract language, onerous term lengths, noncollaborative partners, lack of transparency, and anemic support, if any (just to name a few). For an industry that prides itself on creating and shaping stories that speak to diverse audiences, we should be better at articulating truer narratives about our field.

It doesn’t help that, at Sundance this past year, all one could talk about was how streamers were “less interested in independent film than a few years ago, preferring [instead] to fund movie production internally or lean on movies that they’ve licensed” and how Sundance itself was “financially struggling, presenting fewer films than in previous years and using fewer venues.” (https://www.thewrap.com/sundance-indie-film-struggles-working-business-model) Still others like Megan Gilbride and Rebecca Green in their Dear Producer blog have put forth ideas how Sundance should be reinvented completely.

But we all know that independent film isn’t just about Sundance. We have heard a lot of discussion recently about the need to reshape the narratives we tell ourselves regarding the state of the independent film industry.

Distribution Advocates, which is also doing great work chasing the myths vs. the realities of the field, also believes that we must all question “some of our deepest-held beliefs about how independent films get made and released, and who profits from them.”

In their podcast episode about Exhibition, economist Matt Stoller remarked how “weird” it is that even with all the technology we possess connect audiences, we’re still so “atomized” that all that rises to the top is whatever appears in the algorithm Netflix chooses for us in the first few lines of key art when we log in (and we will note that even the version of the key art you see is itself based on an algorithm).

But is it really all that strange? One of the main reasons that myths exist is that someone is profiting from perpetuating them. The same with networks and platforms and algorithms. And the more layers of middlemen and gatekeepers there are, the harder it is for us to see the forest for the trees. Keeping us in our algorithmically determined silos numbs us into not minding (actually preferring) that we are watching things—or bingeing things—from the safety and comfort of our living rooms. The ability to discover on our own content that aligns with our true interests or consuming content in a communal space has disappeared the same way that the act of handwriting has…we used to be able to do it but haven’t done it in so long that it feels unnatural and too time-consuming to deal with.

Brian Newman / Sub-Genre Media acknowledges that the problems remain real, but that what everyone is calling crisis levels seems to him merely a return to norms that were in place before the bubble burst. No one, he says, is coming to rescue “independent film”—certainly not the streaming platforms, which merely used it as necessary to build a consumer base.

Many have posited myriad ideas about how to bypass the gatekeepers. Newman echoed what TFC has been recently discussion internally: that instead of many competing ideas, we need them to be merged into one bigger idea/solution. Like, for example, an overarching solution layer run by a nonprofit on top of each public exhibition avenue that will aggregate data and help filmmakers connect audiences to their content. A similar idea was also discussed at the last meeting of the Filmmaker Distribution Collective in the context of getting audiences into theaters.

By exclaiming that “No one is coming to the rescue,” Brian really means that we are all in this together, and that it’s going to take a village.

We agree, but a finer point needs to be made.

Every choice we make moving forward—whether you are a filmmaker, distributor, theater owner, or festival programmer, what have you—could possibly be distilled into either a decision for the independent filmmaking public good…or for one’s own professional interest. Saying that a non-profit should come in and offer a solution layer to aggregate data is all well and good until it threatens to put out of business someone whose livelihood is based on acquiring and trafficking in that data. How refreshing was it to be reminded at Getting Real by Mads K. Mikkelsen of CPH:DOX that his festival has no World Premiere requirements? It reminds us of the horrible posturing and gatekeeping film festivals do in the name of remaining relevant and innovative. For us to truly grow out of the predicament we are in, some of us are going to have to voluntarily release some of the controls to which we are so tightly clutching.

Keri Putnam & Barbara Twist have an excellent presentation on the progress of a dataset they are putting together of who is watching documentaries from 2017 – 2022. They provide some other data that was very sobering:

Film festivals: comparing 2019 numbers to 2023 – there was a 40% drop in attendance;

Theatrical: most docs are not released in theaters and attendance is down even for those that are released.

But they also note that there is really great work being done in the non-theatrical space— community centers, museums, libraries – that is not tracked by data. TFC’s Distribution Days offers two sessions on event theatrical and impact distribution, so we’ll be able to see a tiny bit of that data during the conference.

We also know that the educational market is still healthy, and that so many have remarked of the importance of getting young people interested in film…so we have three sessions where we hear from the Acquisitions Directors of 11 different educational distributors.

We also have a panel from folks in the EU who will provide advice on the landscape and how best to exploit films internationally and carve our rights and territories per partner. And we’ll speak to all-rights distributors about what kinds of films they see doing well, what they are doing to support filmmakers—and what their value proposition is in this marketplace.

We have a great panel on accessibility, and two others that relate to festivals and legal agreements.

Starting off with a keynote from noted distribution consultant and impact strategist Mia Bruno, the 2-day conference aims to summarize the state of the industry while providing thought provoking conversations to inspire disruption, facilitate effective collaboration, and to aid broken hearts.

Regardless of whether current days are better or worse than the heydays of Sundance and the independent film of yesteryear, Distribution Days will identify the current obstacles of the independent film distribution landscape, and what we can hold on to—as a commonality—to evolve the landscape together in the future.

If you look a little deeper, you will see that, despite all the challenges, filmmakers have and can still achieve “success” when they understand the terrain, (sometimes) work with multiple partners with a bifurcated strategy, protect themselves contractually, and maintain and grow their own personal audience.

We hope you will join us. And for those of you that cannot make all of the sessions we are offering live on May 2 & 3, you’ll be able to catch up on what you missed via The Film Collaborative website after the conference is over.

We look forward to seeing you next week! And if you have not registered yet, you can do so for free at this link.

David Averbach April 25th, 2024

Posted In: case studies, Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms, DIY, Documentaries, education, Film Festivals, International Sales, Legal, Marketing, Theatrical

All About AVOD? part 2: Is FAST getting FASTER in Europe?

Anyone keeping up with VOD distribution has read that the SVOD streamers are licensing and funding fewer independent films, placing instead more focus on series and productions. While Transactional VOD (TVOD) and Subscription VOD (SVOD) revenues have declined (after being a boon), Ad-supported VOD (AVOD) revenues have come in as the next boon wave. In fact, some of the SVOD players, such as Netflix and Disney+, are adding AVOD tiers to their services.

As we covered in the initial blog about AVOD, it’s been lucrative for certain kinds of content and especially for distributors with libraries of the right kind of content. For example, see Indie Rights’ answers to the questions below and note that for some films (usually with some commercial or strong niche elements and, rarely, docs, as well) can generate high 5-figure and sometimes low 6-figure revenue via AVOD.

What is your overall observation regarding AVOD at this time (2022) with respect to independent film?

I believe that AVOD is an extremely attractive revenue source and opportunity for independent film. We have watched virtually every major player add AVOD to their channels/platforms including Netflix. The advertisers from traditional broadcast will follow the eyeballs and the eyeballs are leaving traditional broadcast and cable and moving to AVOD. Even our fairly new YouTube AVOD channel is doing great and is now our third largest revenue source for our filmmakers. In July, streaming audiences surpassed broadcast audiences in size for the first time and this trend will continue.

What kinds of independent films do you see doing well?

We have successes and failures in all genres. The most successful are films where the filmmaker has thoroughly embraced our concept of “Post, Post,” i.e., actively engaging with their audience using social media currency.

What does that look like in terms of revenues? What kind of films do not do especially well via AVOD?

Straight dramas without a strong niche subtext. Docs without a strong niche audience, i.e. don’t do a doc about your grandfather or friend/relative that survived cancer unless there is a huge reason to do so besides your personal feelings or you are willing to put it on a YouTube channel and give it away.

Please share any marketing/publicity observations/tips including what Indie Rights does and what its filmmakers/licensors do.

We provide our filmmakers with a fifty page marketing bible that lays out the best social media platforms to have a presence on and very specific strategies to use, for example rotating promotions mentioning only a specific channel, so that channel will re-post to a much larger audience, using short video clips from the movie with links as opposed to just continuing to post your trailer over and over, making sure posters are “click-bait”, that trailers are fast moving and that Amazon, IMDb and Rotten Tomato reviews are maximized as all buyers now check these. We also provide our filmmakers with a private group where we can support each other and that we can continually provide them with new resources and industry news. Every filmmaker/production company needs a YouTube Channel because that is the brand and you can build an audience for your entire body of work. Put clips from your move their, interviews with your cast and crew, behind the scenes clips and/or bloopers and always put a link to where people can watch your film first up in the Description. Most people ignore the fact that there are 2.6 billion YouTube active users and that you are most discoverable there. Also, you can get the best demographics there if you are unsure who your audience is.

As always, feel free to share anything else you want to regarding AVOD (including if it’s a comparison to SVOD and TVOD/EST).

We are finding that very few independent films are doing much TVOD these days unless they have a huge waiting audience. SVOD can do OK if you have a very specific niche to market to.

While we endeavored to get more feedback from other established VOD distributors, we need a little more time and will circle back in a part 3 of this blog in early 2023. In the meantime, it’s interesting to note that FAST channels are all the rage and TFC gets approached along with traditional distributors to supply content to emerging FAST channels (typically very niche-specific as FAST channels are meant to be, in part, a solution to that punishment of choice viewers have when facing all the supply via their Smart TVs, computers, and phones). But how successful those FAST channels are and will be is a topic for 2023, since it’s too soon to tell.

In the meantime, please see below for our colleague and friendly VOD guru Wendy Bernfeld’s update about AVOD & FAST outside the United States.

Is FAST getting FASTER in Europe?

by Wendy Bernfeld, Rights Stuff

Backdrop

Earlier in 2022, TFC published Part 1 of what was intended to be a two-part series on AVOD and FAST channels in the U.S. and the licensing opportunities for indie films, whether indirectly via representatives (aggregators, sales agents, other) or directly (limited but occasionally possible). We also addressed impact and angles of marketing, packaging, audience engagement and revenues.

Fast-forward to the end of 2022, and AVOD—and particularly FAST—has exponentially exploded in the U.S. There’s currently a vast landscape with more than 1,400 channels across 22 networks, including via Pluto TV, Xumo, Tubi, Roku, Samsung TV Plus, and Amazon’s Freevee (formerly IMDbTV), to name a few examples. Some of these bigger services (and other AVODS) have begun to cross over to UK and portions of Europe. But in the U.S., we are seeing some starting to drop channels and/or content to focus on more tailored/curated services. Other trends include moving non-exclusive deals to exclusive ones and expanding from merely licensing older content to acquiring higher profile titles, and in some cases even Originals.

Europe

Europe has generally lagged behind the U.S. in terms of AVOD/FAST, with the UK growing quickly but still 2-3 years behind, and rest of Europe trailing behind that, particularly in the non-English language regions. This pattern is not so unusual when one considers that new service launches and business models (including SVOD services, which are the prior window) often begin and grow in U.S. first, before getting rolled out to the UK and other English-speaking regions and then other EU regions sometime later.

Various challenges unique to international have also affected both U.S. services crossing over to the EU (such as Pluto, Roku, Xumo, Samsung TV Plus) as well as new homegrown EU services (like Rakuten, wedotv, etc). These challenges and distinctions include:

- The EU market is more diversified and fragmented in regard to tech, cultural tastes, and cultural requirements (including EU quotas favoring content from EU origin over U.S.).

- Platforms must deal with a patchwork of complex rights issues, generally and particularly regarding AVOD/FAST in Europe. These include issues arising from public and private funders, broadcasters, prior windows (SVOD, Pay TV, etc.), and distribution rights gaps (e.g., local distributors handling only some regions for titles but with rights gaps in others).

- Add to this the need for costly localization (for example, dubs and subtitles) and in FAST channels, a need for a significant and regularly refreshed volume of programming. Overall, this requires a more tailored content rights acquisition for these types of 24/7 services, for each market and its unique content tastes.

- Also, audiences in the EU have very strong offerings of free ad-supported content available (film, tv, docs) via broadcast/free tv (unlike the U.S.). So, in Europe, it’s more of a case for platforms of trying to convince audiences to switch over from their plentiful free-to-air TV to FAST services, or to discover and use them as a complement to their existing TV and SVOD packages.

- Almost 70% of EU households watch ad-supported content free in one form/source or another.

- There’s also a strong paytv, telecom, cable environment in the EU (cheaper packages relatively to the U.S.) and SmartTVs and OTT device penetrations have increased exponentially, but not in all regions of Europe.

- Until recently, the majority of successful TV apps were mainly SVOD or AVOD services in Europe, other than a few more mainstream extensions, such as AVODs for Free TV or Pay/SVOD channels, or, for example, JOYN in Germany (jointly owned by ProSiebenSat.1 and Discovery). [Frankly, they are not a real large buyer for U.S. niche indies/docs.]

2023 EU Opportunities in FAST: Affordable streaming alternative, especially during economic downturns

Since COVID and the explosion of FASTs in the U.S. market, the EU has begun to catch up quickly, driven by:

- the continued rise of devices—connected Television/Smart TVs/OTTs that are rolling out. By now 2/3 of EU households have access

- the increased demand to get other sources of curated, “lean-back” content programming for free. This is perhaps partly due to an SVOD overload, with too many subscriptions and streaming options (subscription fatigue) and difficulties finding what to watch, where—it’s all too much, a virtual paradox of choice

- commercial breaks tend to be shorter in FASTS (5-8 min/hr instead of double that for linear broadcasts) and the ads can be more palatable (new formats, more personalized, targeted)

Content Licensing Opportunities

Although the uptake in EU AVOD/FASTs presents an opportunity for rightsholders, admittedly most will come from mainstream and big brand film/series suppliers, as well as volume aggregators (as discussed in Part 1 of TFC’s AVOD series). The same pattern carries over to Europe.

But there are still some select opportunities for indies, which pop up on a case-by-case basis, depending on the nature of the film and possible matches to the service, including theme, international recognition/acclaim, and other factors:

- some FAST services are seeking deliberately lesser-exposed quality indie or local content for audiences (and what’s older to one viewer may be new to another)

- and, in turn, those FAST services can help indies at least find new audiences abroad, since the channel-flicking nature of FAST helps with discoverability.

- FAST channels and AVOD can help bring a second life to older films, but also various services are increasingly focused on newer content offerings, particularly in niches or themes that fit their channel(s)

Who’s Out There in AVOD/FAST in Europe

For clarity’s sake, I’m not addressing here the separate phenomena of AVOD ‘tiers,’ such as SVODs like Netflix, HBO Max, NBC/Universal’s Peacock, and Disney+, which are premium-priced subscriptions platforms that now also offer a lower priced ‘tier’ (still a subscription, but cheaper because they are supported by ads, and with less features and content —in other words, a subset of the premium service).

Let’s not confuse them with pureplay AVOD or FAST platforms who are buying content specifically for a service supported by ads, free to consumers.

- The main FASTS of course stem (as discussed in Part 1) from studio-backed or other mainstream U.S. services, and/or from device manufacturers—PlutoTV, Roku, (North America, UK, Mexico), Samsung TV Plus, Xumo (via LG), as well as certain EU homegrown services such as Rakuten (detailed further below). Most offer a mix of on-demand (AVOD) and linear FAST, and some have live programming as well.

- Tubi is not yet in Europe. Ironically Fox’s TUBI (in North America, Mexico, Australia, New Zealand) has not yet been able to launch in EU/UK, in part due to GDPR privacy legislation in EU. The very model that makes it successful in personalization/ad revenue generation is a barrier to its ability to crossover to EU.

- There are also FASTs set up by large EU/international rightsholders (Banijay, Fremantle, A&E, ITVx, BBC, All3Media, Corus,). These suppliers already have rights to a volume of titles and can create multiple subchannels of content, whether under their own brand, under thematic categories, or around single titles popularity (e.g., in series).

- These types often naturally begin with and emphasize their own content. But they eventually do add content from third parties (including indies, selectively, where a good match) to supplement and enhance the channels.

- Beyond their U.S. launches, most of the above already have FASTs in the UK.

- Some FASTs are styled as niche thematic channels, such as Blue Ant’s HauntTV (horror), Tribeca’s UK FAST channel, or FilmRise who, among scores of other channels, has 3 free movie channels tailored per market via LG internationally, beyond its offerings in U.S., as well as FilmRise British (in UK, Eire, Nordics, via LG), and FilmRise SciFi (Italy). Other regions will follow in the future.

- A&E (but not yet FAST in the EU); Curiosity Stream (the SVOD’s) FAST channel CuriosityNow in U.S. (but not yet in Europe).

- Not relevant for TFC readers, but many are “single program title” FASTs—like a Baywatch or Australian MasterChef or Midsomer Murders type of channel.

The SmartTV (CTV)-run channels are a mix of all the above.

- Samsung already offers close to 100 free channels through Samsung TV Plus.

- Focused on high brand names, known partners, producers, and distributors, they see AVOD and FAST not just for library titles sitting on a shelf, but as a higher profile bigger window/destination.

- For example, in Germany they acquired the top new Das Boot series in 8K.

- They have O & O (owned and operated) dedicated channels of their own in 5 markets (Netherlands, Sweden, Germany, UK, Spain) but also the ‘single title’ bingeable branded channels (e.g., Baywatch) and curated entertainment hubs (e.g., comedy, entertainment, reality, lifestyle).

- Focused on high brand names, known partners, producers, and distributors, they see AVOD and FAST not just for library titles sitting on a shelf, but as a higher profile bigger window/destination.

- Xumo had earlier also crossed over to EU and also offers, via LG smart TVs, a FAST TV service with more than 190 channels available in France, UK , Germany, and Italy. Some include natural history, drama, or foreign language.

- Paramount’s Pluto TV (part of the ViacomCBS Inc., which is now Paramount Global), already a leader in the U.S. has been expanding aggressively through Europe. It’s just had its 10-year anniversary, apparently, with 70M overall monthly active users (MAU), over $1B in revenue last year, and by now has spread to 25 regions (including beyond US: UK, GAS [Germany Austria Switzerland], Spain, Italy, France, and, via its Viaplay partnership, the Nordics, and in Canada, via Corus, which launched in December 2022).

- They differentiate themselves from other types of FASTS as they are “pureplay” FAST (linear), not a free tv companion/AVOD ‘add on’ like others in the UK (Freevee, ITV, MY5). They already have 150 channels in the UK.

- In the UK, they focus on the opportunity arising from the 3M viewers who have zero linear connection (no free tv) and also an additional 10M who technically have a connection to Cable TV, but who don’t really ‘use’ it, so for them, FAST is the key opportunity to give those viewers a “linear-like” free experience, via CTV.

- In France, they have 100 channels, some focused on film and nonfiction.

- In Nordics, they already partnered with Viaplay SVOD, replacing the former free AVOD Viafree, and this is a model they want to continue in other regions.

Other AVODs but not FAST include:

- Amazon Freevee, formerly IMDb.tv – which just launched in the UK and Germany

- NBCU’s Peacock (part of Sky/Comcast group) launched in UK, GAS, and Italy as part of Sky partnership (subscription and ads angles, but not FAST channels) and some of its content will also follow the path of the new Comcast SVOD SkyShowtime SVOD which rolls out to 20+ EU regions that are not UK, Germany, Italy (so as to not compete with SKY PayTV subscription, not FAST channels).

Homegrown FAST Services in the EU

- The largest, Rakuten TV, for example, offers both TVOD, SVOD, AVOD, and FAST, with 12M viewers across the continent, 95% of them on connected television. Their emphasis is now mostly on AVOD/FAST.

- AVOD: 10,000+ titles (films, docs, series) from the U.S. and the EU/local indies, as well as Rakuten Stories (Originals and Exclusives). Movies here, for example, on the UK side.

- FAST: 90+ free linear channels from global networks, top EU broadcasters and media groups, and the platform’s own thematic channels with curated content (some movies and docs from indies, too).

- Currently in 43 EU regions including in Spain, Portugal, UK/Ireland, France, GAS, Italy, Sweden, Finland, Benelux, Croatia, Portugal,, reaching more than 110M households via SmartTVs/Apps.

- Some examples of channels of interest potentially to our readers include:

- In France WildSide Tv (an offshoot of Wildbunch sales agent style of films/docs, i.e. arthouse/festival) as well as Universcine (indie cinema and fest titles sourced worldwide). Both those FASTS also have SVOD counterparts that preceded the addition of the FAST, so windowing is important.

- Rakuten’s Zylo Emotion’L is a film channel aimed at women with a mix of romance, comedies, and thrillers, while Zylo’s Ciné Nanar Channel, is a new FAST channel dedicated to a mixture of nostalgic movies that focus on action, disaster, and creature movies in the fight and sci-fi/ fantasy realm.

- In Italy they have also added shorts, natural history, nature themed channels

Other EU Players

Beyond mainstreamer JOYN (JV ProSieben and Discovery, with limited opportunities for U.S. indies), there are other local regional smaller AVOD/FAST sites, such rlaxx.tv in Germany (indie movies, series, doc channels, among other genres and niches).

- WEDOTV: (UK/Germany) For indie movie producers/sellers, there’s a stronger appetite in niche content services such as WEDOTV (the late-2022 Rebrand of earlier AVODS WatchFree and Watch4Free) in UK/Germany (both AVOD and FAST). Italy will be added in 2023.

- Wedotv (which includes thematic niches (we do movies, we do docs, etc.) began as AVOD and it remains the mainstay of their service offering (90%), with FAST being used more as a promotional or discovery complementary offering.

- Wedotv is mainly for movies, also tv, and a new documentary channel, as well as more other recent genres.

- Their main focus is movies for AVOD, from all over the world, usually with some cast/distinguishing sales features/festival acclaim, socials. They “don’t need” Oscar winners, but candidate films should be capable of international region traction in terms of cast, theme or acclaim, if not readily recognizable.

- They are increasingly interested in other genres like factual, factual entertainment, and sports.

- They market the service simply as “free to air,” whether FAST or AVOD. Consumers don’t care, although they’d need both rights, respectively.

- After their earlier days of playlists, they now have a more “curated thoughtful approach to programming,” with categories and themes—for example, action night, thriller day, horror night, etc.

- MOJItv: (Benelux) FAST channel (carried on Samsung TV Plus and Rakuten—kids content only

- The Guardian FAST channel: (UK, EU) Launched in spring 2022 on Rakuten TV, it is the “first time The Guardian’s documentaries and videos will appear on a scheduled, linear channel as part of The Guardian’s global digital network.” (source).

Reach: the 43 Rakuten TV regions above (via Samsung, LG, and also via Samsung’s own FAST TV service Samsung TV Plus in select countries.) - SoReal (all3media’s lifestyle TV FAST)

- ITVX: (UK) Just launched in December 2022. SVOD with an AVOD tier and also 20 FAST channels in the UK, which they expect will make FAST more mainstream and help normalize the UK audience’s behavior, which was more traditional in terms of TV viewing and SVOD.

- However, most of the content on ITVX at launch is, predictably, from their own stable – thematic single program channels (such as Inspector Morse, Vera, ITV shows), also themes from their stable: crime drama, classic vintage films, sitcoms, reality formats, true crime), but…

- On the plus side there will also be some third-party content acquisition from indies selectively over time to round out the offering.

- LittleDotStudios: many AVOD channels including 7 FAST channels, many themes would be of interest for TFC viewers and they do buy from indies.

- FASTs: Real Stories, Timeline, Wonder, Real Crime, Real Wild, Real Life, and Don’t Tell the Bride

- For the other channels/YouTube and other AVOD activations, see these links (here and here) for multiple narrower themes you can match your titles with.

- They are actively buying from indies both direct and via sales agents, aggregators, core regions such as the UK, the U.S., other English regions, and then some EU regions, for example, Germany.

- Paying either rev share, MG plus rev share, or flat fees, film dependent – that’s the good news. The bad news is that lately they’re buying in packages of 50 or so titles, and phasing out the ‘’one-offs’’ from indies…but there can be some exceptions.

- TF1’s STREAM: (France) This service is part of myTF1, via Samsung: it offers multiple (40+) FAST/AVOD offering channels, aimed at the French market; some are IP (single title specific, regarding French titles on the broadcaster), while others more genre-led programming (such as archive movies, international dramas – mainly big names like Mad Men, French dramas, thriller, romance, manga/anime, for example).

Pragmatics

Sourcing Deal possibilities: How to reach the platforms?

The EU opportunity is growing in 2023 as opposed to the very overcrowded market in U.S. That’s the good news. But to manage expectations, the bulk of content sourcing by these larger FAST services is first from the content libraries of the studios, distributors, aggregators (as in the Part 1 AVOD blog).

There can be some exceptions for stellar one-offs, but it is easier for the platforms to deal with packages, volume and frequent “refresh.” The smaller niche services (like movies, horror, or LGBTQ+ specialized ones) you can approach directly with more ease.

- If dealing with sales agents, and/or aggregators, some are more active/savvy in this part of the digital sector (beyond the big global platforms) than others, such as Syndicado (Canada), OD MEDIA (Netherlands-based but in 10 regions and dealing with 200 platforms in TVOD, SVOD and now strong in AVOD/FASTS including FASTS of their own), First Hand Films (GAS) (sales agent for docs, social, gender issues, etc. but they are also active in digital and AVOD/FAST), and Abacus Media (UK), all of whom do activity in AVOD/FAST as well.

Age of Film/Windowing

- Films 3-8 years old, as I outlined in my previous TFC blog article on SVODs, were usually possible candidates for acquisition on a non-exclusive basis in the SVOD window for the SVOD platforms beyond the Big Globals. Films older than this fell nicely in the AVOD/FAST window.

- However, those lines are rapidly blurring, and now newer titles (for example, those that are 5 years old or even more current) can be picked up by an AVOD/FAST and occasionally exclusivity can be required. Therefore, it is critical to watch the windowing to avoid shooting yourself in the foot. As mentioned in part 1 of the AVOD blog, sometimes U.S. AVOD revenues can exceed those of SVOD, but that’s not yet the status in UK/EU, which is a few years behind, so this needs to be balanced carefully.

Slanting the pitch

- It is also essential to show [as mentioned in part 1 of the AVOD blog] some connection of your U.S. film to the EU platforms, for example, in theme, cast, IMDb and Rotten Tomatoes ratings, metrics (socials, audience engagement, clever marketing, or packaging/bundling) with other titles in similar category or theme or other hooks (like name cast in your film or elsewhere on the platforms).

- Generally, the overseas EU platforms need to prioritize their own EU originated producers and suppliers (also for content quotas that are express or implied, depending on the region), so it is a lot harder these days to sell a one-off from the U.S. over something originating from the EU.

- That said, U.S. indie content can still have appeal, and one can find other “hooks” to pitch, for example, when we helped producers from the U.S. sell music docs to the EU, we also indicated the massive fan bases of the rock/punk groups in the very regions of Europe where we were selling the film and added film festival or press reviews from those regions so the pitch was more tailored.

- What might be old to someone in the U.S. could be new to someone else in the EU, which is a double-edged sword–either an undiscovered gem that helps the platform differentiate itself, or a unsold film that was unsold for a reason. Handy to address this in the pitch, if relevant.

- Overall, each platform needs different types of content so find your match: niche subjects with traction indeed include paranormal, Sci-Fi, Black, LGBTQ+, action, adventure, horror, fast-paced docs (e.g., music/lifestyle, but also educational). The key is to match….

Basically, if you are able to go direct, or, if indirect, with the support of reps, then it is helpful to do as much as possible to “help do the buyer’s job for them”—and indicate where the film fits in their offerings, or suggest other titles they already have on their site that are comparable, etc.)

Deals

AVOD/FAST revenues: most platforms expect non-exclusive and via rev share, and only some titles are doing well on this basis, if standalone—it’s still early days in the EU.

Some platforms do pay a flat-fee (e.g., 5-figures per title, depending on regions). It helps you have some certainty but then again, they don’t have to share the viewership data/calculations, so to speak. Some of the various larger players are moving in this direction.

In cases of mid-sized or smaller platforms, one can choose, in some cases, not to take a flat fee, but a smaller minimum guarantee (M.G.) plus rev share, or take a larger ongoing rev share for upside (e.g., some platforms offer the indie film the choice). Its platform- and film-specific FAST is too new to have a locked-in model, so at least there is some room for negotiation with the mid-sized and theme/niche platforms overseas, where deals are not negotiable at all (again this depends on the platform and film).

Discovery helps increase ad revenues

- Outside of U.S., as with Part 1 of the AVOD blog, it is even more important when a sale is made (whether by you or your reps) on a AVOD rev share basis, to take steps to actively ensure you help audiences “find your film” on the AVODs/FASTs, so that it doesn’t sit unnoticed in a huge online store (and thus unmonetized).

The bottom line is that it’s important to be familiar with each platform and know how one might best match and search for your film. Pay attention to keywords, genres, formats, and topics actually used on the AVOD and FAST sites, not just the ones you had in metadata from earlier windows.

Wendy would like to note that much of the factual content from the above article was sourced and summarized from the following sources (articles and podcasts):

Articles

WTF are Fast channels (and should advertisers care)? (The Drum, November 25, 2022)

Why Haven’t FAST Services Taken Off in Europe? (Videoweek, April 26, 2021)

La FAST TV accélère en Europe (JDN, March 11, 2022)

FAST channels: The New Grail of Connected TV (Onemip, July 25, 2022)

Ad-Supported Content Will Benefit from Streaming Subscription Overload (SpotX, Sept. 2, 2020)

Samsung TV Plus launched new channels across Europe (Prensario, Oct. 18, 2022)

Samsung TV Plus: AVOD pioneer seeks content partners in Cannes (Onemip, Oct. 14, 2022)

Rakuten TV expands FAST offering in Europe with 21 new channels (Digital TV Europe, Nov. 18, 2021)

The State of European FAST (Variety, Dec. 23, 2022)

Free, Ad-Supported Television Is Catching On FAST: Boosters Hail It As Second Coming Of Cable, But Just How Big Is Its Upside? (Deadline, Dec. 14, 2022)

The Meteoric Rise of Free Streaming Channels: A Special Report (Variety, Dec. 1, 2022)

Podcasts

Samsung on the FAST and AVOD environment | Inside Content Podcast (3Vision, May 4, 2022)

wedotv on the growth of FAST, innovating distribution strategies and harnessing opportunity | Inside Content(3Vision, Dec. 15, 2022)

The Best of FAST with All3Media, Paramount UK and Samsung | Inside Content (3Vision, Nov. 9, 2022)

Orly Ravid December 31st, 2022

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms

All About AVOD? part 1: What To Do with Your Library Title

by David Averbach and Orly Ravid

One of the joys of working at The Film Collaborative is our extended filmmaker family. Some of the filmmakers we work with we have known for decades, back to when they made their first films. Inevitably, after seven-, ten-, or twelve-year terms, many of these filmmakers are getting their rights back from the distributors with whom they originally entered distribution deals.

They often ask us, “What is possible for my film now? What can I do to give it a second life?”

(We should state that the vast majority of these filmmakers do not have obviously commercial projects that could simply be offered to a different large streaming service like Netflix or Hulu. They are the type of films that TFC handles: solid films with good or at least decent festival pedigrees and proper distribution at the time of their initial release.)

Unfortunately, there is no one answer for every film. Nor is there a fixed answer for each type of film, as platforms’ needs can change at the drop of a hat. Except that all platforms seem to have an endless appetite for true crime docs, but we digress…

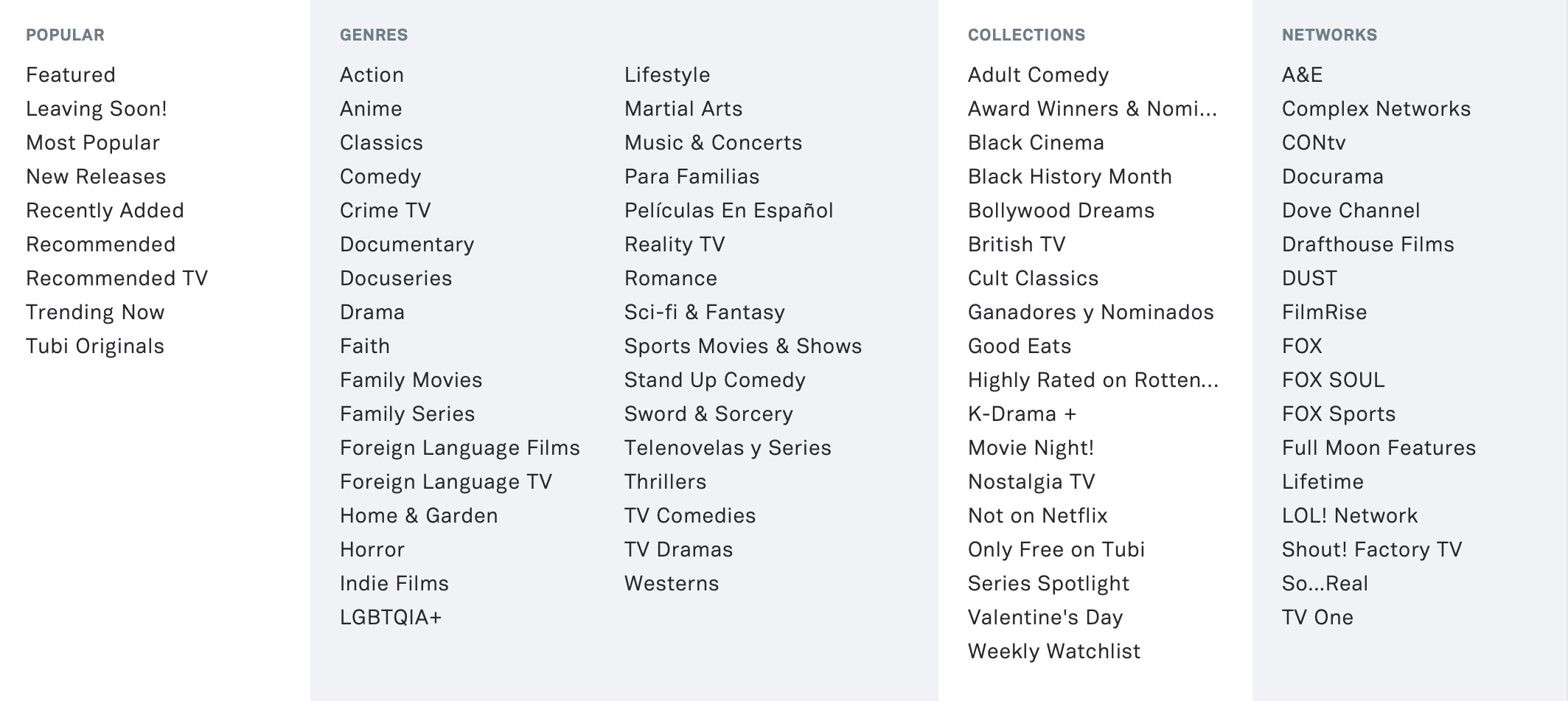

So, this blog article is less of a “how to” for library titles, and more of a “how to think” about them.

Certainly, there are non-exclusive subscription-based (SVOD) platforms that align with various content areas, such as Documentary+, Topic, Wondrium, Curiosity Stream, Coda, Qello, Tastemade, Gaia, Revry, and many more (check out our Digital Distribution Guide for more info). These are platforms that offer a revenue share based on minutes watched. Since they may have not been in existence when the filmmakers’ original distribution deals were arranged, they are definitely worth exploring when one (or more) of them is a fit for your project.

But there are also ad-supported (AVOD) platforms1, which are free to the end user and rely on commercials that play before the film starts. Generally speaking, AVOD platforms seem to be more lucrative in terms of revenue than specialized SVOD platforms, and we’ve heard that some films are making “real” money them (more on that later). While there’s no guarantee that AVOD platforms will bring in more money than SVOD platforms, or much money at all, this at least makes sense, anecdotally: with the rise in commercial streaming services and especially since the start of the pandemic, folks are watching increasingly more content, but actually spending less above and beyond the Netflix/Amazon Prime/HBO/Disney etc. combination of platforms that they have ostensibly come to view as basic utilities.2 So AVOD provides a win-win for platforms and consumers alike.

Until recently, filmmakers have been somewhat reluctant to place their films on AVOD platforms, but they are coming to realize what distributors have known for a few years now—that AVOD can continue to bring in revenue when transactional platforms such as iTunes are no longer performing for a film the way they might have at the beginning of their digital run.

So, we set out to ask what we believed was a simple question: which AVOD platforms are taking which type of library content? The Film Collaborative has some limited experience with AVOD platforms, but we felt it prudent to talk to some folks that do this day in and day out. To that end, we reached out to Nick Savva, Vice President of Content Distribution at Giant Pictures, and Tristan Gregson, Director of Licensing & Distribution at BitMAX.

The answer turns out to be a complicated one. Here’s why:

Most AVOD platforms are looking for all kinds of content. One of the trends that has been occurring for the past few years is the addition of new platforms, not just in the U.S., but globally. And the pandemic has accelerated existing trends, so there are even more new platforms than ever. These platforms are not going to be able to produce or acquire enough new content to justify their existence, so they rely on library titles as much as they do new releases. So, the good news is that there are more outlets and revenue opportunities for library titles than ever.

The not-so-great news is that sometimes AVOD platforms are actually looking for specific types of films, but only for a limited time to fill a specific need. Platforms have a good sense of what percentage of their films are, for example, comedies, dramas, thrillers, horror, documentaries, true crime, etc. When they look at who is watching what, if comedies are overperforming on the platform relative to the percentage of titles they occupy overall, the platform may not take as many comedies for a while until that changes, or they could decide to double down and take more comedies at the expense of other types of films. Conversely, if there is a category that is underperforming, they could decide that they need some fresh meat in that category, or simply decide to take less of it.3

So why exactly is this bad news? Because as the needs of AVOD platforms ebb and flow, the entities with the best chance of succeeding are those that can respond quickly to calls from these platforms for specific content. A high percentage of the work Giant Pictures does with AVOD platforms involves their distributor clients, who use Giant as a sort of white label service. Giant is tasked with placing their content libraries on these platforms because these distributors don’t have the bandwidth to keep up with which platforms want what from month to month. Similarly, BitMAX works with many studios to deliver to these platforms, but the studios are the ones handling the licensing. What this means is that the bulk of content going to AVOD platforms is coming from the content libraries of studios and distributors. That is not to say that films from individual filmmakers aren’t being placed on AVOD platforms by Giant/BitMAX, it’s just that studios and distributors are their go-to sources for content because they can provide a bunch of titles with a quick turnaround.

The sad reality here is that AVOD is one area of distribution where middlemen are being added to the mix in a way that makes it harder for individual filmmakers to take back control of their films.

Many of the filmmakers who have just gotten their rights back often remark to us how glad they are to have done so, as if they are finally getting out of a bad marriage. Even if the relationship wasn’t such a badmarriage, this sentiment—justified or not—perhaps stems from the fact that their TVOD sales had dropped over the years and they felt like their distributor was no longer doing anything for their film, or that they were tired of not receiving reporting because there were long periods of time with no earnings. The last thing they appear to want to do is start up a new relationship with a new distributor or aggregator and incur more encoding costs for a shot in the dark in terms of being accepted by these platforms only to earn $12 a quarter in earnings.

It’s important to really have a look at the reporting your old distributor provided you. There’s a good chance that simply re-creating what your old distributor did—perhaps your film was already on AVOD platforms—is going to give you a completely different outcome. But to the extent that your project has not been tested in the current landscape, what should a filmmaker be thinking about if they find themselves in the position of deciding whether to go it alone or offer their film to another distributor?

It’s Your Time and Money

Bandwidth:

Tristan Gregson remarked that the same rules apply for library titles as when just starting out, and his stance was the following: if you know how to engage your audience then put it somewhere. If not, then don’t. Whether you try to go it on your own or partner with another distributor, unless there is someone that’s going to remind your audience that it’s there, there’s a good chance your film will sit unnoticed in a glut of content. This is going to take some effort and while a new distributor might do a bit of marketing, you are going to have to get creative. Perhaps time the re-release of this older film with a new project of yours?

Cost:

If you go through an aggregator like BitMAX, you are probably looking at a bare minimum of $2,000 for encoding, QC, and delivery and to pitch and deliver to a few SVOD or AVOD platforms. It’s a fee for service, so they will be hands off when it comes to strategy, and uninvolved when it comes to your earnings. If a distributor like Giant Pictures is willing to work with you, it can cost twice that much, but they will be real partners in the sense that they will be proactive in helping you come up with a strategy. They will also take a certain percentage of your earnings. You may also be able to negotiate lower encoding costs in exchange for an increased percentage of your earnings.

What is in it for the Platform?

Metrics:

Nick Savva advises filmmakers to think about your film like a platform would: what are your film’s metrics? These scores can tell a lot about the public’s level of familiarity with your film, and there are data tracking services that distributors and platforms use to determine them. Also among the first things that an acquisitions team would look at would be indications of basic audience awareness, such as the of the number of positive reviews on Amazon, or the ratings on IMDb. If the metrics are good, a deal might be attractive to a platform. Are there any recent reviews? In other words, does your film still hold up?

Is there one Platform that is better for my film than others?

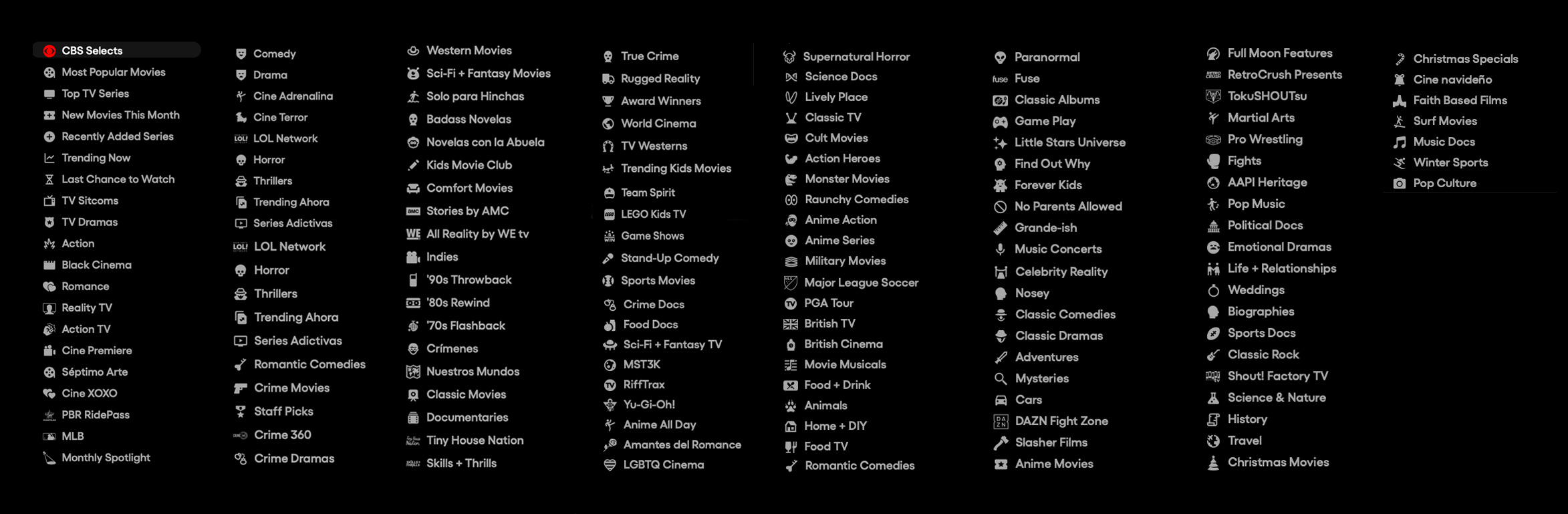

Honestly, there are not all that many AVOD platforms in the U.S. Tubi, Pluto, Roku, Peacock, IMDb TV, and a few others. The good thing about AVOD is that most deals are non-exclusive, meaning that you can be on more than one at once. But should you apply for all of them? How does one decide?

Signal Boost:

The following might not be possible for every film, but, if possible, try to think about the likely television habits of your audience and the specifics of each platform and take advantage of the free signal boost.

People are very familiar with platforms like Netflix and Hulu, but when it comes to platforms like Tubi or Pluto, why would one choose to watch one over the other? The answer might be simpler than you would think!

Does your film have a TV star in it? If they are on the FOX network, chances are that audiences will see ads for Tubi, because Fox is the parent company of Tubi. If they are on NBC, then perhaps Peacock or Xumo will be advertised.

There are also tricks that might apply for documentaries too. Pluto just became available in Latin America and Mexico, so films with Latinx content might want to consider that platform first.

One of The Film Collaborative’s digital distribution titles, The Green Girl, has been doing extremely well on Pluto, but not so well on Tubi or Roku, and for the longest time we couldn’t figure out why. Then it hit us: this documentary is about an actress who famously appeared on the 1960s television show Star Trek. Since Pluto is owned by Viacom, which is the parent company of Paramount, Pluto is the AVOD destination platform for Trekkies!

Keywords:

Make sure your keyword game is strong. Aggregators and distributors will ask you to fill out a metadata sheet with genres/keywords, but you must make sure the choices conform to actual categories and genres on the platforms, which can differ from one another and evolve over time. Distributors have even admitted that it’s hard for them to keep up sometimes, especially if such metadata is capture via web interface. Case in point: The Film Collaborative placed a few films we have been working with for years onto Tubi, but the keywords that we chose when we first submitted the film to our aggregator were based on iTunes genres, which are very narrow. Cut to the films getting up onto Tubi, and they were almost impossible to find without searching for their exact titles. It’s been several months, and we are still struggling, with the help of our aggregator, to get these updated on the platform. Bottom line is that it’s important to be familiar with each platform and know how one might best search for your film and be proactive to ensure that the proper information is being delivered to each platform at the time of delivery.

Pluto TV (owned by CBS/Viacom) offers a dizzying array of genres/categories to choose from (they appear in a vertical sidebar and seem to rearrange themselves periodically)

Tubi’s current “Browse” navigation tab. Tubi’s parent company is Fox Corporation.

Very Mini Library Titles Case Study

We talked to director/producer Kim Furst, whose rights to her 2014 film Flying the Feathered Edge: The Bob Hoover Project came back to her after her aggregator (Juice) declined to renew the term. She expressed that she did not want to use another aggregator like Distribber/Quiver/Bitmax/FilmHub because there was a concern that they might not be around in another 5 years. (As you probably are aware, Distribber has shuttered, and Quiver is not currently accepting films from individual filmmakers and will probably turn into something else).

So, she went with Giant Pictures.

The cost to re-encode was about $4K. While she did not feel great about having to shell out such a huge chunk of cash on a library title, Kim still felt that the film still had life in it, and she wanted to try other distribution avenues, such as public television, that she never managed to do when the film originally came out.

We should note that one of the reasons why Giant might have been interested in the film was that it is narrated by Harrison Ford. The film is about Bob Hoover, an American fighter pilot and air show aviator, and Ford has a longstanding love of flying planes. So, there is some commercial appeal that can be leveraged here.

She is at the stage where they have initiated the re-release. Right now, the film is back up on TVOD platforms, including being re-placed on Amazon, which Giant was able to accomplish despite the platform’s embargo on unsolicited non-fiction content.

We asked Kim to report back on what happens next. We suggested that she note where all of Harrison Ford’s top movies are on AVOD and take note if that platform sees any boost from the connection.

Revenue Range

With so many variables and permutations, it’s hard to give a real range in terms of what’s possible for a library title on AVOD, especially since it’s impossible to know when we are talking about the revenue of a “library” title—as opposed to that of a title that enters AVOD as part of their “new release” window.

When I asked Tristan about revenue, he acknowledged that to even talk about it would put us into “anecdotal space,” because he isn’t aware of what it took for some of his clients to earn, for example, 5 figures during an AVOD revenue period, as compared with other clients who were only able to earn, say, 3 figures. While he admitted that he has seen a single independent film title clear quite a bit, he also reiterated to me that at a certain point of revenue generation, distributors tend to get involved with a title to signal boost, so it isn’t exactly “a fair comparison to those independents working day in and day out to make a few grand on their title. But if the message is that you don’t have to be working with one of the major studios to reach seven figures in revenue, it can still very much be accomplished in this current age of VOD releasing.”

Nick spoke more specifically to AVOD, noting that they “have had a couple of indie titles which have generated $100k+ royalties in 1 month on 1 AVOD platform. But, of course, those are outliers.”

One of our filmmakers told us that they have two filmmaker friends-of-friends (whose films deal with Black Cinema content) for whom Tubi is paying well: one reported $15K a month in residuals while the other one says they are making $4-6K a month on a movie released 10 years ago. Both filmmakers allegedly went through an aggregator, but their friend said they were reluctant to allow the names of their respective films to be shared publicly.

So, as Tristan remarked, it’s best not to hold too tightly onto evidence that is merely anecdotal, because TFC certainly knows films that are making almost nothing on AVOD.

Notes:

1. As we were conceiving this article on Library titles, and realizing how important AVOD could be for an older title, Tiffany Pritchard of Filmmaker Magazine approached us about an article she and Scott Macaulay were writing about AVOD. Its title is Commercial Breaks and it is available in the January 2022 issue of the magazine (behind paywall, at least for now).

2. As a reference, this article discusses how shorter theatrical windows might be accelerating TVOD decline and shows the increase in both spending and subscription stream share from 2019 to 2021. Others, however, predict that streaming services will lose a lot of subscribers in 2022. Still, it’s hard to know how streaming services are faring, as many of them are not transparent in their total number of subscribers and average revenue per year.

3. Stephen Follows assembled a team, called VOD Clickstream, that uses clickstream data to analyze viewing patterns on Netflix between January 2016 and June 2019. He also offers a ton of information on his website. In November 2020, he presented a talk entitled, “Calculating What Types of Film and TV Content Perform Best on SVOD?”, in which he outlined how he believed Netflix navigates how popular a genre is versus what percentage of content of that genre is available on the platform.

David Averbach February 8th, 2022

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms, DIY, Documentaries, technology

The Evolution of the Education Market

Our guest blog author this month is Vanessa Domico, who has more than 30 years of business experience in both the corporate and non-profit sectors. In 2000, Vanessa joined the team of WMM (Women Make Movies), first as the Marketing and Distribution Director, and eventually Deputy Director. Wanting to work more closely with filmmakers, Vanessa left WMM in 2004 to start Outcast Films.

Our guest blog author this month is Vanessa Domico, who has more than 30 years of business experience in both the corporate and non-profit sectors. In 2000, Vanessa joined the team of WMM (Women Make Movies), first as the Marketing and Distribution Director, and eventually Deputy Director. Wanting to work more closely with filmmakers, Vanessa left WMM in 2004 to start Outcast Films.

As the summer winds down and the new school year approaches, Outcast Films is revving up marketing initiatives for our fall releases. Rolling around in the back of my head is how much technology has changed the business of film distribution: everything from how we position the films to our audience of teachers and librarians to how we deliver the films.

Our primary goal at Outcast is servicing our customers: teachers and librarians. These are the folks that are going to pay money to purchase and rent your film. I think you will agree with me that if teachers and librarians don’t know about the fantastic new documentary you just finished, then what’s the point?

When I started Outcast Films in 2004, we were distributing VHS tapes. A few years later, DVDs (and Blu-rays) hit the market and VHS tapes were quickly made obsolete. Now, here we are in 2018, with educational digital platforms like Kanopy, AVON (Alexander Street Press), and Hoopla, all of whom service the educational and library markets, not to mention Amazon, Netflix, iTunes and so on, digital is moving at light speed forward.

Two years ago, 95% of our income came from DVD sales. Last year that number dropped to 75% and halfway through this year DVD sales only represent approximately 45% of our total sales. By the end of 2020, I believe DVDs will be just like VHS tapes and dinosaurs. There will be some DVD/Blu-ray sales, of course, but for students, teachers, and the increased demand for on-line college classes in the U.S. digital is the future. The problem is technology should work for everyone—big and small – and it doesn’t.

For this blog, I am focusing solely on the educational market, which is Outcast Films’ area of expertise. But giant tech companies like Amazon, Netflix and Hulu also play a huge factor especially in collapsing the markets. For a couple years now, Netflix has been demanding hold back rights for up to three years from the educational platforms like Kanopy and AVON. Now other big tech companies are placing the same demands on producers: you can come with us or go with Kanopy. Most filmmakers will obviously take the bigger money contracts. (I know I would.) But ultimately, this is driving the cost down for consumers which is good for all of us who like to watch films but bad for the bank accounts of filmmakers.

Kanopy’s collection has comprised of approximately 30,000 titles and AVON has over 100,000. It is impossible for these platforms, to market all their films, all the time. That is not a knock against Kanopy or AVON, I think they have been leaders in the industry and I have a tremendous amount of respect for them. They are providing a great service that students and teachers love.

However, a recent monitoring of VIDLIB, a listserv frequented by academic librarians, reveals that many of them are beginning to rail against some platforms like Kanopy and AVON. You can access the entire discussion by signing up for the VIDLIB listserv but for your convenience, I’ve included some anonymous excerpts below:

- “We are concerned about our rising costs from Kanopy”

- “I believe many of us could not foresee just how expensive streaming, DSLs, etc. would cost us in the long run.”

- “Librarians jobs have become more accountant in nature than collection development.”

- “Trying to balance the needs of faculty/our community for access with a commitment to continue to develop and maintain a lasting collection is difficult.”

- “Our IT department is over-taxed as is and does not have the resources to devote to hosting streaming video files.”

- “We basically had to stop all collection development.”

- “The paradox of increasing production and availability of media resources and shrinking acquisition budgets, due to streaming costs is a disturbing trend, particularly when considering that 100% of our video budget went to DVD acquisitions just four years ago.”

- “(our budget for DVDs) is $20,000 and there’s no way we can purchase in-perpetuity rights for digital files; and, really, there’s no way we can ‘do it all’ or meet all needs.”

- “We love Kanopy – but when it costs $150/year to just provide access, not ownership, to one title, it’s really, really hard to justify.”

- “State legislators are beginning to put pressure on schools to find ways to reduce the cost of things like books, etc.”

- “When colleges and universities are already under fire for the cost of textbooks, etc., asking students to pay one more additional cost gets lumped into the argument about the increasing cost of higher education.”

The concerns these librarians have expressed have been on a slow simmer the last few years but it’s only a matter of time before they hit a full-on pasta boil. One of the most significant concerns, and the one that will affect filmmakers most, is the high cost of streaming.

Another factor that we need to consider is the copyright law and the “Teacher’s Exemption”. With the help of the University of Minnesota, the law is simplified below:

- The Classroom Use Exemption

- Copyright law places a high value on educational uses. The Classroom Use Exemption (17 U.S.C. §110(1)) only applies in very limited situations, but where it does apply, it gives some pretty clear rights.

- To qualify for this exemption, you must: be in a classroom (“or similar place devoted to instruction”). Be there in person, engaged in face-to-face teaching activities. Be at a nonprofit educational institution.

- If (and only if!) you meet these conditions, the exemption gives both instructors and students broad rights to perform or display any works. That means instructors can play movies for their students, at any length (though not from illegitimate copies!)

In other words, if a teacher is going to use the film in their classroom, and they teach in a public university or high school, they do not need anybody’s permission to stream the film to their students.

That’s not the best news for filmmakers but I always say: facts are your friends. Knowing that they won’t need your permission, what can you do to ensure teachers see (and love) your film?

Stay with me because I’m going to ask you to do a little math:

If a librarian has a budget of $20,000 a year for films, at an average cost of $150 for a one-year digital site license (DSL), then they can expect to rent approximately 133 DSLs a year. According to Quora, there are nearly 10,000 films currently being made each year and that number is growing (thanks in large part to technology.) The bottom line is that you have a 1.3% chance that your film will be rented by that university or college. If we increase the library’s budget 5 times, your chance increases to 6.5% which are not great odds.

Facts are our friends. If independent film producers and companies like Outcast Films are going to survive in this volatile business, we need to embrace the facts to solve the problems which means doing your homework. Filmmakers who think they have a great film for the educational market, will have to make their film available through digital platforms. But if they want to increase their odds of selling the film, you will also have to do their own marketing – or hire someone who has experience in the business to help you.

Here are a few tips to help you get started:

- Define and establish your goals as soon as possible

- Write copy for your film with your audience in mind (i.e. teachers are going to want to know how they can use this film in their class)

- Organize a college tour before you turn over the rights of the film

- In the process, find academic advocates who will present the film at conferences AND recommend it to their librarians.

The educational market is a very important audience to reach for many filmmakers. I think most folks reading this blog would agree there is not a better way to educate than by using film. The educational market can also be lucrative, but librarians cannot sustain the increase in costs for steaming over the long haul. As information flows freely through technology, teachers are becoming savvy to the business and realize they don’t need permission to stream a film in their classroom if they respect the criteria set forth in the copyright law.

Remember, facts are our friends. If you think your film is perfect for the educational market, then do your homework: research, strategize and find partners who will help you.

David Averbach August 1st, 2018

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, education, Netflix, Uncategorized

Making Distribution Choices with Your Film

A recent online web series featured our founder, Orly Ravid, as well as some powerhouse guests in indie film producing and distribution, hosted by WestDocOnline. Here is what we learned from the 1 hour+ panel, primarily focused on documentaries.

- Music clearance is important. Surprisingly, many new filmmakers do not realize that any music used in a film must be licensed, both the publishing (the person who wrote the song) and the master (the entity that recorded the song) rights must be secured. Distribution contracts cannot be signed if music clearance has not been secured on your film. This is especially crucial for anyone looking to make a music documentary. For a good primer on this, visit this article: A Filmmaker’s Guide to Music Licensing .

- A devoted core fanbase can make a film successful. Richard Abramowitz named several documentaries that his company has theatrically distributed that had an excited and motivated fanbase that could be tapped into with less marketing money than a wide audience film.

- There is value in having a global marketing campaign, rather than one territory at a time. Cristine Dewey of ro*co films champions the idea that if your domestic distributor is already launching a marketing campaign, much of which will be found by audiences outside of the U.S. because of online marketing, it makes sense to time theatrical releases in other countries to coincide.

- Revenues from documentary sales. Netflix will pay anywhere from low 5 figures to high 6 or even 7 figures for documentaries. It depends on the film’s pedigree. Also, Amazon Festival Stars program was offering $200,000 to filmmakers at the Toronto International Film Festival in exchange for making Amazon Video Direct the exclusive SVOD home for the film. Filmmakers can wait up to 18 months to upload to the platform, allowing for further festival and theatrical revenue.

- Distribution is a business. While it is all great and good to produce a film using credit cards, an iPhone and the good will of your friends, distribution is an integral part of the process and needs a budget. “In what world would someone say I have a great idea for a pencil. I’m going to raise $100,000 to make pencils. Then you have a warehouse filled with pencils, and then think about how you will get these into Staples? That’s not a business plan, that’s lunacy. But every day, people do that because this is art. Hope is not a strategy. You have to have a plan and you have to have a budget,” says Richard Abramowitz. “What’s the point of making the film if no one sees it?Marketing and distribution budgeting is the only way to assure the film will get seen and make an impact, short of an excellent marketing commitment by an honest distributor, something so relatively few documentary films enjoy,” said Orly Ravid.

To watch the full panel, find it below.

Sheri Candler January 10th, 2018

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms, Documentaries, International Sales, Marketing

Tags: Cristine Dewey, film distribution, Jonathan Dana, Orly Ravid, Richard Abramowitz, roco films, The Film Collaborative

What Nobody Will Tell You About Getting Distribution For Your Film; Or: What I Wish I Knew a Year Ago.

By Smriti Mundhra

Smriti Mundhra is a Los Angeles-based director, producer and journalist. Her film A Suitable Girl premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2017 and is currently playing at festivals around the world, including Sheffield Doc/Fest and AFI DOCS. Along with her filmmaking partner Sarita Khurana, Smriti won the Albert Maysles Best New Documentary Director Award at the Tribeca Film Festival.

I recently attended a panel discussion at a major film festival featuring funders from the documentary world. The question being passed around the stage was, “What are some of the biggest mistakes filmmakers make when producing their films?” The answers were fairly standard—from submitting cuts too early to waiting till the last minute to seek institutional support—until the mic was passed to one member of the panel, who said, rather condescendingly, “Filmmakers need to be aware of what their films are worth to the marketplace. Is there a wide audience for it? Is it going to premiere at Sundance? Don’t spend $5 million on your niche indie documentary, you know?”

Immediately, my eyebrow shot up, followed by my hand. I told the panelist that I agreed with him that documentaries—really, all independent films—should be budgeted responsibly, but asked if he could step outside his hyperbolic example of spending $5 million on an indie documentary (side note: if you know someone who did that, I have a bridge to sell them) and provide any tools or insight for the rest of us who genuinely strive to keep the marketplace in mind when planning our films. After all, documentaries in particular take five years on average to make, during which time the “marketplace” can change drastically. For example, when I started making my feature-length documentary A Suitable Girl, which had its world premiere in the Documentary Competition section of this year’s Tribeca Film Festival, Netflix was still a mail-order DVD service and Amazon was where you went to buy toilet paper. What’s more, film festival admissions—a key deciding factor in the fate of your sales, I’ve learned—are a crapshoot, and there is frustratingly little transparency from distributors and other filmmakers when it comes to figuring out “what your film is worth to the marketplace.”

Sadly, I did not get a suitable answer to my questions from the panelist. Instead, I was told glibly to “make the best film I could and it will find a home.”

Not acceptable. The lack of transparency and insight into sales and distribution could be the single most important reason most filmmakers don’t go on to make second or third films. While the landscape does, indeed, shift dramatically year to year, any insight would make a big difference to other filmmakers who can emulate successes and avoid mistakes. In that spirit, here’s what I learned about sales and distribution that I wish I knew a year ago.

As any filmmaker who has experienced the dizzying high of getting accepted to a world-class film festival, followed by the sobering reality of watching the hours, days, weeks and months pass with nary a distribution deal in sight can tell you, bringing your film to market is an emotional experience. This is where your dreams come to die. A Suitable Girl went to the Tribeca Film Festival represented by one of the best agent/lawyers in the business: The Film Collaborative’s own Orly Ravid (who is also an attorney at MSK). Orly was both supportive and brutally honest when she assessed our film’s worth before we headed into our world premiere. She also helped us read between the lines in trade announcements to understand what was really going on with the deals that were being made – because, let’s face it, who among us hasn’t gone down the rabbit hole of Deadline.com or Variety looking for news of the great deals other films in our “class” are getting? Orly kept reminding us that perception is not reality, and that many of these envy-inducing deals, upon closer examination, are not as lucrative or glamorous as they may seem. Sometimes filmmakers take bad deals because they just don’t want to deal with distribution, have no other options, and can’t pursue DIY, and by taking the deal they get that sense of validation that comes with being able to say their film was picked up. Peek under the hood of some of these trade announcements, and you’ll often find that the money offered to filmmakers was shockingly low, or the deal was comprised of mostly soft money, or—even worse—filmmakers are paying the distributors for a service deal to get their film into theaters. There is nothing wrong with any of those scenarios, of course, if that’s what’s right for you and your film. But, there is often an incorrect perception that other filmmakers are somehow realizing their dreams while you’re sitting by the phone waiting for your agent to call.

Depressed yet? Don’t be, because here’s the good news: there are options, and once you figure out what yours are, making decisions becomes that much easier and more empowering.

Start by asking yourself the hard questions. Here are 12+ things Orly says she considers before crafting a distribution strategy for the films she represents, and why each one is important.

- At which festival did you have your premiere? “Your film will find a home” is a beautiful sentiment and true in many ways, but distributors care about one thing above all others: Sundance. If your film didn’t beat the odds to land a slot at the festival, you can already start lowering your expectations. That’s not to say great deals don’t come out of SXSW, Tribeca, Los Angeles Film Festival and others, but the hard truth is that Sundance still means a lot to buyers. Orly also noted that not all films are even right for festivals or will have a life that way, but they can still do great broadcast sales or great direct distribution business – but that’s a specific and separate analysis, often related to niche, genre, and/or cast.

- What is your film’s budget? How much of that is soft money that does not have to be paid back, or even equity where investors are okay with not being paid back? In other words, what do you need to net to consider the deal a success? Orly, of course, shot for the stars when working on sales for our film, but it was helpful for her to know what was the most modest version of success we could define, so that if we didn’t get a huge worldwide rights offer from a single buyer she could think creatively about how to make us “whole.”

- What kind of press and reviews did you receive? We hired a publicist for the Tribeca Film Festival (the incomparable Falco Ink), and it was the best money we could have spent. Falco was able to raise a ton of awareness around the film, making it as “review-proof” as possible (buyers pay attention if they see that press is inclined to write about your film, which in many cases is more important to them than how a trade publication reviews it). We got coverage in New York Magazine, Jezebel, the Washington Post and dozens of other sites, blogs, and magazines. Thankfully, we also got great reviews in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, and even won the Albert Maysles Prize for Best New Documentary Director at Tribeca. Regardless of how this affected our distribution offers, we know for sure we can use all this press to reignite excitement for our film even if we self-distribute. On the other hand, if you’re struggling to get attention outside of the trades and your reviews are less than stellar, that’s another reason to lower expectations.

- What are your goals, in order of priority? Are you more concerned with recouping your budget? Raising awareness about the issues in your film (impact)? Or gaining exposure for your next project/ongoing career? And don’t say “all three”—or, if you do, list these in priority order and start to think about which one you’re willing to let go.

- How long can you spend on this film? If your film is designed for social impact, do you intend to run an impact/grassroots campaign? And can you hire someone to handle that, if you cannot? Do you see your impact campaign working hand in hand with your profit objectives, or separately from them? The longer you can dedicate to staying with your film following its premiere, the more revenue you can squeeze out of it through the educational circuit, transactional sales, and more. But that time comes at a personal cost and you need to ask yourself if it’s worth it to you. Side note: touring with your film and self-distributing are also great ways to stay visible between projects, and could lead to opportunities for future work.

- Does your film have sufficient international appeal to attract a worldwide deal or significant territory sales outside of the United States? If you think yes, what’s your evidence for that? Are you being realistic? By the way, feeling strongly that your film has a global appeal (as I do for my film) doesn’t guarantee sales. I believe my film will have strong appeal in the countries where there is a large South Asian diaspora—but many of those territories command pretty small sales. Ask your agent which territories around the world you think your film might do well in, and what kinds of licensing deals those territories tend to offer. It’s a sobering conversation.

- Does your film fit into key niches that work well for film festival monetization and robust educational distribution? For example, TFC has great success with LGBTQ, social justice, environmental, Latin American, African American, Women’s issues, mental health. Sports, music, and food-related can work well too.