TFC’s Distribution Days is upon us!

Next week, The Film Collaborative is holding a free virtual distribution conference, Distribution Days, which will offer concrete takeaways on the state of indie distribution and how filmmakers can navigate it. Attendees will hear from exhibitors, distributors, consultants, and filmmakers, some with case studies, as they describe and reflect on the landscape.

This conference hopes to help filmmakers develop critical thinking skills around distribution by looking at what is and what is not viable within a traditional distribution framework. It will also offer some alternative approaches. Willful blindness or a doomsday mindset are equally unproductive.

So, we are offering this pre-conference primer to set the tone, take stock of what myths are out there, and talk about what thought leaders in this space are coming up with as ways to deal with the current landscape.

Here we go!

Remember the days when creators and distributors were lying back in their easy chairs, proclaiming their satisfaction with how independent cinema has been evaluated by the marketplace? Yeah, we don’t either…and we’ve been in the industry (in the U.S.) for more than two decades. Nevertheless, there is a pervading sense that the state of independent film has never been worse—and that we’ve been going downhill from this mythic “better place” ever since Sundance was founded in 1978.

Why do we insist on bemoaning a Paradise Lost when the truth is that being a filmmaker has never been a paradise? Filmmakers have always been confronted with predatory distributors, dense and confusing contract language, onerous term lengths, noncollaborative partners, lack of transparency, and anemic support, if any (just to name a few). For an industry that prides itself on creating and shaping stories that speak to diverse audiences, we should be better at articulating truer narratives about our field.

It doesn’t help that, at Sundance this past year, all one could talk about was how streamers were “less interested in independent film than a few years ago, preferring [instead] to fund movie production internally or lean on movies that they’ve licensed” and how Sundance itself was “financially struggling, presenting fewer films than in previous years and using fewer venues.” (https://www.thewrap.com/sundance-indie-film-struggles-working-business-model) Still others like Megan Gilbride and Rebecca Green in their Dear Producer blog have put forth ideas how Sundance should be reinvented completely.

But we all know that independent film isn’t just about Sundance. We have heard a lot of discussion recently about the need to reshape the narratives we tell ourselves regarding the state of the independent film industry.

Distribution Advocates, which is also doing great work chasing the myths vs. the realities of the field, also believes that we must all question “some of our deepest-held beliefs about how independent films get made and released, and who profits from them.”

In their podcast episode about Exhibition, economist Matt Stoller remarked how “weird” it is that even with all the technology we possess connect audiences, we’re still so “atomized” that all that rises to the top is whatever appears in the algorithm Netflix chooses for us in the first few lines of key art when we log in (and we will note that even the version of the key art you see is itself based on an algorithm).

But is it really all that strange? One of the main reasons that myths exist is that someone is profiting from perpetuating them. The same with networks and platforms and algorithms. And the more layers of middlemen and gatekeepers there are, the harder it is for us to see the forest for the trees. Keeping us in our algorithmically determined silos numbs us into not minding (actually preferring) that we are watching things—or bingeing things—from the safety and comfort of our living rooms. The ability to discover on our own content that aligns with our true interests or consuming content in a communal space has disappeared the same way that the act of handwriting has…we used to be able to do it but haven’t done it in so long that it feels unnatural and too time-consuming to deal with.

Brian Newman / Sub-Genre Media acknowledges that the problems remain real, but that what everyone is calling crisis levels seems to him merely a return to norms that were in place before the bubble burst. No one, he says, is coming to rescue “independent film”—certainly not the streaming platforms, which merely used it as necessary to build a consumer base.

Many have posited myriad ideas about how to bypass the gatekeepers. Newman echoed what TFC has been recently discussion internally: that instead of many competing ideas, we need them to be merged into one bigger idea/solution. Like, for example, an overarching solution layer run by a nonprofit on top of each public exhibition avenue that will aggregate data and help filmmakers connect audiences to their content. A similar idea was also discussed at the last meeting of the Filmmaker Distribution Collective in the context of getting audiences into theaters.

By exclaiming that “No one is coming to the rescue,” Brian really means that we are all in this together, and that it’s going to take a village.

We agree, but a finer point needs to be made.

Every choice we make moving forward—whether you are a filmmaker, distributor, theater owner, or festival programmer, what have you—could possibly be distilled into either a decision for the independent filmmaking public good…or for one’s own professional interest. Saying that a non-profit should come in and offer a solution layer to aggregate data is all well and good until it threatens to put out of business someone whose livelihood is based on acquiring and trafficking in that data. How refreshing was it to be reminded at Getting Real by Mads K. Mikkelsen of CPH:DOX that his festival has no World Premiere requirements? It reminds us of the horrible posturing and gatekeeping film festivals do in the name of remaining relevant and innovative. For us to truly grow out of the predicament we are in, some of us are going to have to voluntarily release some of the controls to which we are so tightly clutching.

Keri Putnam & Barbara Twist have an excellent presentation on the progress of a dataset they are putting together of who is watching documentaries from 2017 – 2022. They provide some other data that was very sobering:

Film festivals: comparing 2019 numbers to 2023 – there was a 40% drop in attendance;

Theatrical: most docs are not released in theaters and attendance is down even for those that are released.

But they also note that there is really great work being done in the non-theatrical space— community centers, museums, libraries – that is not tracked by data. TFC’s Distribution Days offers two sessions on event theatrical and impact distribution, so we’ll be able to see a tiny bit of that data during the conference.

We also know that the educational market is still healthy, and that so many have remarked of the importance of getting young people interested in film…so we have three sessions where we hear from the Acquisitions Directors of 11 different educational distributors.

We also have a panel from folks in the EU who will provide advice on the landscape and how best to exploit films internationally and carve our rights and territories per partner. And we’ll speak to all-rights distributors about what kinds of films they see doing well, what they are doing to support filmmakers—and what their value proposition is in this marketplace.

We have a great panel on accessibility, and two others that relate to festivals and legal agreements.

Starting off with a keynote from noted distribution consultant and impact strategist Mia Bruno, the 2-day conference aims to summarize the state of the industry while providing thought provoking conversations to inspire disruption, facilitate effective collaboration, and to aid broken hearts.

Regardless of whether current days are better or worse than the heydays of Sundance and the independent film of yesteryear, Distribution Days will identify the current obstacles of the independent film distribution landscape, and what we can hold on to—as a commonality—to evolve the landscape together in the future.

If you look a little deeper, you will see that, despite all the challenges, filmmakers have and can still achieve “success” when they understand the terrain, (sometimes) work with multiple partners with a bifurcated strategy, protect themselves contractually, and maintain and grow their own personal audience.

We hope you will join us. And for those of you that cannot make all of the sessions we are offering live on May 2 & 3, you’ll be able to catch up on what you missed via The Film Collaborative website after the conference is over.

We look forward to seeing you next week! And if you have not registered yet, you can do so for free at this link.

David Averbach April 25th, 2024

Posted In: case studies, Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms, DIY, Documentaries, education, Film Festivals, International Sales, Legal, Marketing, Theatrical

Don’t Just “Take the Plunge” in a Distribution Deal

Part 1: Know What You Are Saying “Yes” To • by Orly Ravid

Part 2: Thank U (4 Nothing), Next • by David Averbach

Part 3: Goals, Goals, Goals • by Orly Ravid and David Averbach — COMING SOON

Part 1: Know What You Are Saying “Yes” To

by Orly Ravid

We know from filmmakers the reasons they often choose all rights distribution deals, even when there is no money up front and no significant distribution or marketing commitment made by the distributor. Regardless of whether the offer includes money up front, or a material distribution/marketing commitment, we think filmmakers should consider the following issues before granting their rights.

The list below is not anything we have not said before, and it’s not exhaustive. It’s also not legal advice (we are not a law firm and do not give legal advice). It is another reminder of what to be mindful of because independent film distribution is in a state of crisis, and we are seeing a lot of filmmakers be harmed by traditional distributors.

Questions to ask, research to do, and pitfalls to avoid

- Is this deal worth doing?: Before spending time, money, and energy on the contract presented to you by the distributor, ask other filmmakers who have recently worked with the distributor if they had a good (or at least a decent) experience. Did the distributor do what it said it would do? Did it timely account to the filmmakers? These threshold questions are key because once a deal is done, rights will have been conveyed. So ask that filmmaker (and also decide for yourself) whether they would have been better served by either just working with an aggregator or doing DIY, rather than having conveyed the rights only to be totally screwed over later.

- Get a Guaranteed Release By Date (not exact date but a “no later than” commitment): If you do not get a “no later than” release commitment, your film may or may not be timely released and, if not, the point of the deal would be undermined.

- Get express specific distribution & marketing commitments and limitations / controls on recoupable expenses: To the extent filmmakers are making the choice to license rights because of certain distribution promises or assumptions about what will happen, all of that should be part of the contract. If expenses are not delineated and/or capped, they could balloon and that will impact any revenues that might otherwise flow to the filmmakers. There is a lot more to say about this including marketing fees (not actual costs, but just fees) and also middlemen and distribution fees. But since we are really not trying to give legal advice, this is more to raise the issues so that filmmakers have an idea of what to think about.

- Getting Rights back if distributor breaches, becomes insolvent, or files for bankruptcy: Again, lots to say about this which we will avoid here, but raising the issue that if one does not have the ability to get their rights back (and their materials back) in case a distributor materially breaches the contract, does not cure it, becomes insolvent, or files for bankruptcy, then filmmakers will be left having their rights tied up without any recourse or access to their due revenues. It’s a horrible situation to be in and is avoidable with the right legal review of the agreement. Of course, technically having rights back and having the delivery materials back does not cancel already done broadcasting, SVOD, AVOD and/or other licensing agreements, nor can one just direct to themselves the revenues from platforms or any licensees of the sales agent or distributor (short of an agreement to that end by the parties and the sub-licensees)…but we will cover what is and is not possible in terms of films on VOD platforms in the next installment of this blog.

- Can you sue in case of material breach? Another issue is, when there is material breach, does the contract allow for a lawsuit to get rights back and/or sums due? Often sales agents and distributors have an arbitration clause which means that the filmmakers have to spend money not only on their lawyer(s) but also on the arbitrator. Again, there is much more to say about this, but we just wanted to raise the issue here. There are legal solutions for this, but distributors also push back on them, which gets us back to the first point, is this deal worth doing? Because if the distributor’s reputation is not great or even just good, and, on top of that, if it will not accommodate reasonable comments (changes) to the distribution deal that would contractually commit the distributor to some basic promises and therefore make the deal worth doing and protect the filmmaker from uncured material breach by the distributor, then why would you do that deal?

Filmmakers too often just sign distribution agreements without understanding what they are signing or without hiring a lawyer who knows distribution well enough to review the agreement. This is foolish because once the contract is signed and the delivery is done, the film is out of the filmmakers’ hands and they will have to live with the deal they made. If that deal was not carefully vetted and negotiated, then the odds are that it will not be good for the filmmaker. Filmmakers can make their own decisions, but we urge them to be informed.

How to best be informed:

- Get a lawyer who knows distribution

- Check out our Case Studies

- Read the Distributor ReportCard to see what other filmmakers have said about a distributor and/or find filmmakers to talk to on your own who have used them recently. If we haven’t covered a certain distributor in the DRC but one of our films has used them, just contact us. We could be happy to ask them if they’d be willing to speak with you, and, if so, make an introduction.

Part 2: Thank U (4 Nothing), Next

By David Averbach

When TFC started our digital aggregation program[1] in 2012, there was a palpable sense of possibility, that things were changing–access was opening up, and filmmakers were finally being given a more even playing field. Who needed middlemen when one could go direct [2]!?

In many ways, going direct, choosing to self-distribute, was (and maybe still is) viewed a bit like electing to be single, as opposed to the “security” of a relationship and/or a marriage. When your film gets distribution, it’s a little bit like, “They said, ‘yes!’ Somebody loves me. I don’t have to go it alone.” Less stigma, more legitimacy.

Relationships and distribution deals have a lot in common. If you are breaking up with your distributor, it can get messy. That’s why TFC Founder Orly Ravid has outlined above some of the basic concepts and things you can do with your lawyer to make sure that if you choose to do a deal, you protect yourself as you enter into a binding relationship. Like a pre-nup. So that you get to keep everything you brought with you into said relationship when you part ways.

Good News, Bad News

So, let’s say there is good news in the sense that you are able to hang on to whatever belongings you brought into the relationship.

But there’s bad news, too. Your ex is keeping all the stuff you bought together.

At least it’s going to feel like that. I know…you would rather kick your ex out and stay in your apartment. Really, I get it. But it’s not going to happen. It’s going to feel like your ex has all your stuff and won’t give it back. Because you are not going to feel grateful like Ariana; you will want someone to blame. But that’s not really fair. Because it’s more like you are both getting kicked out of the apartment and technically your partner still owns all the stuff that’s still inside, but also that they changed the locks and neither one of you can get back inside and access it. And, also, you are now homeless. Good times.

OK, let’s back up for anyone confused by the breakup metaphor: You got the rights to your film back.[3] Yay! Your film is up on all these platforms. All you want to do is keep it up on those platforms. Sorry, not gonna happen. You’re going to have to start again from scratch.

Why you have to start from scratch with most platforms when you get your rights back.

I know, you have questions. From a common-sense perspective, it makes zero sense. I’m going to go through the reasons as to why this is the case, on a sort of granular, platform-focused basis, but the answers I think say a lot about how the distribution industry is and, in many ways, has always been set up. And it underscores everything I’ve always suspected about the sorry state of independent film distribution.

I have to thank Tristan Gregson, an associate producer and an aggregation expert of many years, who was generous enough with his time to rerun questions that filmmakers have asked him over the years about salvaging an existing distribution strategy, and why, unfortunately, it is pretty much impossible.

So, let’s begin by limiting our parameters. I mentioned shared materials that were created after your deal was signed. If your distributor created trailers and artwork, I suppose that technically they own the rights, even though your distributor probably recouped their cost, but the train has left the station on those, so how likely is it that someone would go after you for continuing to use them? I would recommend making sure you have a copy of the ProRes file for your trailer and layered Photoshop files (along with fonts and linked files) or InDesign packages for your posters before things go south, because you are going to need the originals again when you start over. I’m assuming you still possess the master to your actual feature. And don’t forget about your closed captioning files.

Licensing deals (that ones that come with licensing fees) have been harder to come by for many years, but if your distributor has licensed your film to a platform, the license itself would be unaffected, so that would not have to be “recreated,” so to speak.

The rest—the usual suspects: transactional platforms (TVOD), rev-share based subscription platforms (SVOD), and ad-supported platforms (AVOD) (in other words, situations where revenue is earned only when the film is watched)—are what I’m going to be focusing on here.

Let’s say your film is up on a handful of TVOD and/or AVOD platforms. Why is it not possible for them to remain up on those platforms?

In the best of all possible worlds, couldn’t somebody simply flip a switch, change some codes, and point all the pages where your film currently lives to a new legal entity and let you continue on your merry distribution way?

But who exactly is this “someone”? They would have to have a direct contact at the platform. So maybe that’s your distributor, maybe it’s their aggregator. And is this contact at the platform the person who will do this? Probably not. It’s probably someone who deals with the tech. So now, you need to mobilize a small army of hypothetical people who are all willing to do this work for you for free. For each platform that you’re on. And don’t forget things between you and your distributor are complicated and tense right now. They are going to do you a favor to save you a few thousand bucks?

But it’s actually worse than that. You would also be assuming that Platform X, who perhaps is also trying to sell books, goods, phones and tablets, actually cares one single iota about your tiny (but fantastic) little film enough to do this for you. They do not. Despite happily taking 30-50% of your selling price for all these years. They absolutely do not.

The Nitty Gritty

I had suspected this, but I sought out Tristan for confirmation. I had only spoken previously to Tristan on a handful occasions, but he is an affable guy. Gregarious but not to the point of being garrulous. He cares. Talking to him, you get the feeling that he would go the extra mile for you if he could. Please remember this as he recites answers that he has probably given more times than he can count. His cynicism is well earned…it comes from experience.

[Note: I’ll ask and answer some of my own questions in places. Tristan’s responses will be in italics, mine will be in plain font.]

You are my distributor’s aggregator. Can’t I just work with you directly?

The answer is yes, if you start from scratch. But your distributor paid for the initial services. They paid to have it placed there. Not you.

But I made the film, and I got my rights back. Why can’t you tell Platform X to keep it up there and just change where the money should go?

Yes. I know your name is listed. But that string of 1s and 0s is associated with your distributor, not you.

It all comes back to tech. Because at the end of the day, it’s a string of 1’s and 0’s that are associated with a media file. It’s not your movie in a storefront or on a digital shelf or anything like that. In the encoding facility/aggregator world, these 1’s and 0’s are the safety net for us. We have an agreement with Party X. If Party X ends the relationship or ceases to exist, it’s written into that agreement that we pull everything down—we kill it from our archives. We’re protecting everyone. We don’t want to hold onto assets that we don’t have any relationship with. Those strings of 1’s and 0’s that go up onto a platform, and that platform has an ID tag that’s tied with the back end of the system, and that system reconciles the accounting, and the accounting reconciles with the payout. We can’t go in and just change a name on a list. That’s just not how that works.

You (the independent filmmaker with a movie) do not have a relationship, direct or indirect, with any of the platforms your distributor placed your title onto. As such, your title would not continue to be hosted at any of these outlets should your relationship with your distributor officially end. People often would say “it’s my movie, now that Distributor X is gone, just have the checks go to me.” That’s not how the platform or the aggregator ever see it, which I know is very painful for the creator who may now think they control “all their rights.”

It’s just a business entity change.

Aren’t you going to be sending me a new file anyway? Isn’t the producer card or logo going to change at the beginning the film? That’s gotta be QC’d again, in any event.

Are you telling me that if I had a 100-film catalogue, I’d have to re-QC 100 titles from scratch? That’s insane.

Let’s say Beta Max Unlimited Films had 100 titles with us and then, Robinhood Films, who is also a client of ours comes along and says, ‘Hey, we bought Beta Max Unlimited Film’s catalog, we bought all the rights to all of it. Work with us to move it over. All you guys have to do is do it on the accounting end.’ Let’s say we would be willing to do it. And let’s say we contact Platform X, we were to talk to them, talk to our rep there, and they say they are willing to relink all that media on their end, they’ll move the 1’s and 0’s over. Even then, 99 times out of 100, it never happens because you’ve got a bunch of people, and these people are kind of working pro bono on something that doesn’t really matter to them.

Just because you may think something is easy or “no work at all” doesn’t make it true, and even when it is, nobody wants to work for free. Something may be technically possible, but having all the different parties communicate and execute just never happens when nobody’s directly being paid to do the actual work.

Are you kidding me? Platform X wouldn’t move a mountain for a hundred titles?

Like, that’s nothing to them, it means nothing. What matters to them—is that stuff plays seamlessly, and it has been QC’d and approved and published. They don’t need to deviate from this because at the end of the day, it’s not going to help sell tablets and phones.

And again, we’re talking about multiple platforms. What happens if they could do this… and they get 6 out of 8 platforms to comply but the other two are intransigent? They’re going to come back to you and say, “Sorry, we tried. We hounded them 16 times, but these two won’t do it. And now you have to pay anyway to redeliver if you want to be on these two platforms.” You are going to think the aggregator is scamming you. It will not be a good look for them. Why would they want to agree to work for free with the likelihood that they will end up looking bad in the end? KISS (Keep it simple, stupid). It only makes sense to ask you to start from scratch.

Are there platforms I can actually go direct with?

You can do Vimeo On Demand on your own. (Note that for top earners [top 1%], there may be an extra bandwidth charge. You can read more about that here).

You can also do Amazon’s Prime Video Direct.

Altavod, Filmdoo, Popflick…More on these later.

I thought Amazon wasn’t taking documentaries?

I believe that’s still true? However, I have access to a small distributor’s Amazon Video Direct portal. In 2021, there was a big, visible callout that said something to the effect of, “Prime Video Direct doesn’t accept unsolicited licensing submissions for content with the ‘Included with Prime’ (SVOD) offer type. Prime Video Direct will continue to help rights holders offer fictional titles for rent/buy (TVOD) through Prime Video. At this time Amazon Prime does not accept short films or documentaries.” This is June 2023. I cannot find this language anywhere in the portal. But I believe that is still the case.

What about “Amazon Prime” SVOD?

In the portal, all the territories that were once available for SVOD are still “listed,” it’s just that the SVOD column whereby you could check each one off is gone. So, no SVOD for unsolicited fiction. If you create your own Amazon Video Direct account, the territories that are available in an aggregator’s account might differ from an individual filmmaker’s account. All this seems to be moot if SVOD is not available.

So, for Amazon, it’s only TVOD?

Yes.

[Sidebar: It has usually just been US, UK, Germany, and Japan. Amazon just announced Mexico, but for this option to be available in your portal, one needs to click a unique token link that was sent out. The account I have access to received this notification. I am not certain whether this link was or will be sent out to all users. Localization is required for the non-English speaking territories in this category.]

But my distributor had gotten my documentary onto Amazon. If I have to start from scratch with my own account, is there a way to convince them to once again allow it in?

Best of luck with that. Amazon is notoriously difficult and unresponsive, even with aggregators. You can try, and even if it is initially rejected, there is an appeal link somewhere in the portal that you can write in to. I have no idea if that will do any good.

My film was Amazon Prime SVOD. If I have to start from scratch with my own account, is there a way to convince them to keep it in there?

“Keeping it” is not the most accurate way of looking at the situation. It’s basically going to create a new page. And that will be controlled by the back-end in your personal account. SVOD will probably not be an option in this account. You can write in, as mentioned above, but it seems as though Amazon is trying to lessen the content glut for its Prime Video service, so I have my doubts as to whether very many people who make this request prevail.

Wait…what??! You mean that I will have a new page and therefore will lose all my reviews?

Yes and no. The old page and reviews might still be there, but “currently unavailable” to rent or buy. But on your page, the page where it is available, the reviews will not carry over. Reviews not carrying over is probably true for all platforms, but Amazon reviews are more prominent than on other platforms, so they are usually what filmmakers care about the most.

My distributor had gotten my film onto AVOD platforms Tubi / Roku / Pluto TV, etc. Do I have a better chance of getting my “pitch” accepted because it was on there before?

No.

But why? It was making some pretty good money.

You are assuming that the Tubi / Roku / Pluto TV, etc. acquisitions person is the same person who approved your film in the first place, and even then, they are going to remember your film, or are going to take the time to look up your film and see how it was doing, and also that amount of earnings you may have gotten is going to mean enough to them to matter.

If I somehow could convince someone to keep assets in place, there’s no downside, right?

Actually, that may not be true. It’s about media files meeting technical requirements, which change over time. What was acceptable yesterday isn’t always acceptable today. So when you attempt to change anything at the platform level, you risk removal of those assets already hosted on a platform.

OK, I think you get the point.

Tristan reminded me that you need to think of yourself as a cog in the tech machine.

You think all this is too cynical? Think about it…

It’s always been that way, even though we never wanted to believe it. Take the Amazon Film Festival Stars program circa 2016 as an example. A guaranteed MG. Sounded great. But on a consumer-facing level, did they make any attempt to create a section on their site/platform where discovery of these purported gems could take place? No. Did you ever stop to ask yourself why? Because at the end of the day, they didn’t really care. Any extra money they would have made was so insignificant to them that it was not worth the effort. So, they discontinued the program and blamed lack of interest.

To be fair, iTunes for many years had a very selective area for the independent genre. But it’s gone/hidden/trash now with AppleTV+. They would rather peddle their own wares than create a section that champions festival films. And remember that one, poor guy who I shall not name that you had to write to and beg in order to get your film even considered for any given Tuesday’s release? Even if you were lucky enough to be selected, if your film didn’t perform well enough it would be gone from that section by Friday morning. Or by Tuesday of the following week. All that seems to be gone now. Independent films don’t make money for them. Even though they are willing to spend $25M on CODA and $15M on Cha Cha Real Smooth.

And every so often, new platforms (like Altavod, Filmdoo, Popflick) emerge that want to change this. There are films that you actually recognize, that have played in festivals alongside yours…just…listed all together! But, have you heard of these platforms, let alone rented a film off one of them platforms or paid a monthly subscription fee? Chances are you haven’t.

This is not to blame you. But by all means, check these mom-and-pop platforms out and support your fellow filmmakers. And these are not the type of platforms that would be so hard to re-deliver to anyway. They’d probably be happy to go direct with you. It’s the big platforms that are calling cards, the ones that everyone uses, that you will want to be on even if you secretly know they are not bringing in much in terms of revenue. But either way, these platforms don’t care.

Let’s remember why aggregators exist. It’s because platforms don’t care, couldn’t be bothered, and waived their magic wand over some labs out there and said, “Now you deal with them. You be the gatekeepers.” And a whole business sector was created.

There are some distributors out there who have been around for a while that may very well have contacts at some of these platforms, but it doesn’t matter. You don’t have those connections, and chances are that they are drying up for these distributors, too.

And while this is crushing, it might also be freeing.

Tristan echoed what TFC has been saying for years: You are your own app, your own thing, most importantly, your own social media marketing campaign.

If you think about getting into bed with a distributor being like a relationship or a marriage, then your film is the kid you are raising. What kind of parent is your distributor? What kind of parent are you? Your distributor might say they will do marketing (change the dirty diapers), and then do it once or twice, but then they don’t do it again. Who is going to change those diapers it if it’s not you?

So, this relationship metaphor I am positing should not solely be directed at filmmakers who are getting their rights back. When you enter into a deal with a distributor, some filmmakers think they can now be deadbeat parents, when in reality you should co-parenting. And when your relationship with your distributor ends, you still need to raise the kid, right? It’s all on you now. And the truth is, it always was.

Notes:

[1] TFC discontinued our flat-fee digital distribution/aggregation program in 2017. [RETURN TO TOP]

[2] When we say “direct,” we mean direct to a platform, or semi-direct through an aggregator that doesn’t have a real financial stake in your distribution, as opposed to a distributor that takes rights and is (or purports to be) a true partner in your film’s distribution strategy. [RETURN TO TOP]

[3] It’s important to ensure that you have your rights back. Easiest and best way is to ask your lawyer and go through it with them both in terms of your distribution agreement, but also on a platform by platform basis. Also, to the extent that you will need to start from scratch, make sure your distributor’s assets on each platform have been removed or disabled before you attempt to redeliver them to each platform. [RETURN TO TOP]

Part 3: Goals, Goals, Goals

By Orly Ravid and David Averbach

Coming soon

admin June 8th, 2023

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distributor ReportCard, DIY, education, Legal

All About AVOD? part 2: Is FAST getting FASTER in Europe?

Anyone keeping up with VOD distribution has read that the SVOD streamers are licensing and funding fewer independent films, placing instead more focus on series and productions. While Transactional VOD (TVOD) and Subscription VOD (SVOD) revenues have declined (after being a boon), Ad-supported VOD (AVOD) revenues have come in as the next boon wave. In fact, some of the SVOD players, such as Netflix and Disney+, are adding AVOD tiers to their services.

As we covered in the initial blog about AVOD, it’s been lucrative for certain kinds of content and especially for distributors with libraries of the right kind of content. For example, see Indie Rights’ answers to the questions below and note that for some films (usually with some commercial or strong niche elements and, rarely, docs, as well) can generate high 5-figure and sometimes low 6-figure revenue via AVOD.

What is your overall observation regarding AVOD at this time (2022) with respect to independent film?

I believe that AVOD is an extremely attractive revenue source and opportunity for independent film. We have watched virtually every major player add AVOD to their channels/platforms including Netflix. The advertisers from traditional broadcast will follow the eyeballs and the eyeballs are leaving traditional broadcast and cable and moving to AVOD. Even our fairly new YouTube AVOD channel is doing great and is now our third largest revenue source for our filmmakers. In July, streaming audiences surpassed broadcast audiences in size for the first time and this trend will continue.

What kinds of independent films do you see doing well?

We have successes and failures in all genres. The most successful are films where the filmmaker has thoroughly embraced our concept of “Post, Post,” i.e., actively engaging with their audience using social media currency.

What does that look like in terms of revenues? What kind of films do not do especially well via AVOD?

Straight dramas without a strong niche subtext. Docs without a strong niche audience, i.e. don’t do a doc about your grandfather or friend/relative that survived cancer unless there is a huge reason to do so besides your personal feelings or you are willing to put it on a YouTube channel and give it away.

Please share any marketing/publicity observations/tips including what Indie Rights does and what its filmmakers/licensors do.

We provide our filmmakers with a fifty page marketing bible that lays out the best social media platforms to have a presence on and very specific strategies to use, for example rotating promotions mentioning only a specific channel, so that channel will re-post to a much larger audience, using short video clips from the movie with links as opposed to just continuing to post your trailer over and over, making sure posters are “click-bait”, that trailers are fast moving and that Amazon, IMDb and Rotten Tomato reviews are maximized as all buyers now check these. We also provide our filmmakers with a private group where we can support each other and that we can continually provide them with new resources and industry news. Every filmmaker/production company needs a YouTube Channel because that is the brand and you can build an audience for your entire body of work. Put clips from your move their, interviews with your cast and crew, behind the scenes clips and/or bloopers and always put a link to where people can watch your film first up in the Description. Most people ignore the fact that there are 2.6 billion YouTube active users and that you are most discoverable there. Also, you can get the best demographics there if you are unsure who your audience is.

As always, feel free to share anything else you want to regarding AVOD (including if it’s a comparison to SVOD and TVOD/EST).

We are finding that very few independent films are doing much TVOD these days unless they have a huge waiting audience. SVOD can do OK if you have a very specific niche to market to.

While we endeavored to get more feedback from other established VOD distributors, we need a little more time and will circle back in a part 3 of this blog in early 2023. In the meantime, it’s interesting to note that FAST channels are all the rage and TFC gets approached along with traditional distributors to supply content to emerging FAST channels (typically very niche-specific as FAST channels are meant to be, in part, a solution to that punishment of choice viewers have when facing all the supply via their Smart TVs, computers, and phones). But how successful those FAST channels are and will be is a topic for 2023, since it’s too soon to tell.

In the meantime, please see below for our colleague and friendly VOD guru Wendy Bernfeld’s update about AVOD & FAST outside the United States.

Is FAST getting FASTER in Europe?

by Wendy Bernfeld, Rights Stuff

Backdrop

Earlier in 2022, TFC published Part 1 of what was intended to be a two-part series on AVOD and FAST channels in the U.S. and the licensing opportunities for indie films, whether indirectly via representatives (aggregators, sales agents, other) or directly (limited but occasionally possible). We also addressed impact and angles of marketing, packaging, audience engagement and revenues.

Fast-forward to the end of 2022, and AVOD—and particularly FAST—has exponentially exploded in the U.S. There’s currently a vast landscape with more than 1,400 channels across 22 networks, including via Pluto TV, Xumo, Tubi, Roku, Samsung TV Plus, and Amazon’s Freevee (formerly IMDbTV), to name a few examples. Some of these bigger services (and other AVODS) have begun to cross over to UK and portions of Europe. But in the U.S., we are seeing some starting to drop channels and/or content to focus on more tailored/curated services. Other trends include moving non-exclusive deals to exclusive ones and expanding from merely licensing older content to acquiring higher profile titles, and in some cases even Originals.

Europe

Europe has generally lagged behind the U.S. in terms of AVOD/FAST, with the UK growing quickly but still 2-3 years behind, and rest of Europe trailing behind that, particularly in the non-English language regions. This pattern is not so unusual when one considers that new service launches and business models (including SVOD services, which are the prior window) often begin and grow in U.S. first, before getting rolled out to the UK and other English-speaking regions and then other EU regions sometime later.

Various challenges unique to international have also affected both U.S. services crossing over to the EU (such as Pluto, Roku, Xumo, Samsung TV Plus) as well as new homegrown EU services (like Rakuten, wedotv, etc). These challenges and distinctions include:

- The EU market is more diversified and fragmented in regard to tech, cultural tastes, and cultural requirements (including EU quotas favoring content from EU origin over U.S.).

- Platforms must deal with a patchwork of complex rights issues, generally and particularly regarding AVOD/FAST in Europe. These include issues arising from public and private funders, broadcasters, prior windows (SVOD, Pay TV, etc.), and distribution rights gaps (e.g., local distributors handling only some regions for titles but with rights gaps in others).

- Add to this the need for costly localization (for example, dubs and subtitles) and in FAST channels, a need for a significant and regularly refreshed volume of programming. Overall, this requires a more tailored content rights acquisition for these types of 24/7 services, for each market and its unique content tastes.

- Also, audiences in the EU have very strong offerings of free ad-supported content available (film, tv, docs) via broadcast/free tv (unlike the U.S.). So, in Europe, it’s more of a case for platforms of trying to convince audiences to switch over from their plentiful free-to-air TV to FAST services, or to discover and use them as a complement to their existing TV and SVOD packages.

- Almost 70% of EU households watch ad-supported content free in one form/source or another.

- There’s also a strong paytv, telecom, cable environment in the EU (cheaper packages relatively to the U.S.) and SmartTVs and OTT device penetrations have increased exponentially, but not in all regions of Europe.

- Until recently, the majority of successful TV apps were mainly SVOD or AVOD services in Europe, other than a few more mainstream extensions, such as AVODs for Free TV or Pay/SVOD channels, or, for example, JOYN in Germany (jointly owned by ProSiebenSat.1 and Discovery). [Frankly, they are not a real large buyer for U.S. niche indies/docs.]

2023 EU Opportunities in FAST: Affordable streaming alternative, especially during economic downturns

Since COVID and the explosion of FASTs in the U.S. market, the EU has begun to catch up quickly, driven by:

- the continued rise of devices—connected Television/Smart TVs/OTTs that are rolling out. By now 2/3 of EU households have access

- the increased demand to get other sources of curated, “lean-back” content programming for free. This is perhaps partly due to an SVOD overload, with too many subscriptions and streaming options (subscription fatigue) and difficulties finding what to watch, where—it’s all too much, a virtual paradox of choice

- commercial breaks tend to be shorter in FASTS (5-8 min/hr instead of double that for linear broadcasts) and the ads can be more palatable (new formats, more personalized, targeted)

Content Licensing Opportunities

Although the uptake in EU AVOD/FASTs presents an opportunity for rightsholders, admittedly most will come from mainstream and big brand film/series suppliers, as well as volume aggregators (as discussed in Part 1 of TFC’s AVOD series). The same pattern carries over to Europe.

But there are still some select opportunities for indies, which pop up on a case-by-case basis, depending on the nature of the film and possible matches to the service, including theme, international recognition/acclaim, and other factors:

- some FAST services are seeking deliberately lesser-exposed quality indie or local content for audiences (and what’s older to one viewer may be new to another)

- and, in turn, those FAST services can help indies at least find new audiences abroad, since the channel-flicking nature of FAST helps with discoverability.

- FAST channels and AVOD can help bring a second life to older films, but also various services are increasingly focused on newer content offerings, particularly in niches or themes that fit their channel(s)

Who’s Out There in AVOD/FAST in Europe

For clarity’s sake, I’m not addressing here the separate phenomena of AVOD ‘tiers,’ such as SVODs like Netflix, HBO Max, NBC/Universal’s Peacock, and Disney+, which are premium-priced subscriptions platforms that now also offer a lower priced ‘tier’ (still a subscription, but cheaper because they are supported by ads, and with less features and content —in other words, a subset of the premium service).

Let’s not confuse them with pureplay AVOD or FAST platforms who are buying content specifically for a service supported by ads, free to consumers.

- The main FASTS of course stem (as discussed in Part 1) from studio-backed or other mainstream U.S. services, and/or from device manufacturers—PlutoTV, Roku, (North America, UK, Mexico), Samsung TV Plus, Xumo (via LG), as well as certain EU homegrown services such as Rakuten (detailed further below). Most offer a mix of on-demand (AVOD) and linear FAST, and some have live programming as well.

- Tubi is not yet in Europe. Ironically Fox’s TUBI (in North America, Mexico, Australia, New Zealand) has not yet been able to launch in EU/UK, in part due to GDPR privacy legislation in EU. The very model that makes it successful in personalization/ad revenue generation is a barrier to its ability to crossover to EU.

- There are also FASTs set up by large EU/international rightsholders (Banijay, Fremantle, A&E, ITVx, BBC, All3Media, Corus,). These suppliers already have rights to a volume of titles and can create multiple subchannels of content, whether under their own brand, under thematic categories, or around single titles popularity (e.g., in series).

- These types often naturally begin with and emphasize their own content. But they eventually do add content from third parties (including indies, selectively, where a good match) to supplement and enhance the channels.

- Beyond their U.S. launches, most of the above already have FASTs in the UK.

- Some FASTs are styled as niche thematic channels, such as Blue Ant’s HauntTV (horror), Tribeca’s UK FAST channel, or FilmRise who, among scores of other channels, has 3 free movie channels tailored per market via LG internationally, beyond its offerings in U.S., as well as FilmRise British (in UK, Eire, Nordics, via LG), and FilmRise SciFi (Italy). Other regions will follow in the future.

- A&E (but not yet FAST in the EU); Curiosity Stream (the SVOD’s) FAST channel CuriosityNow in U.S. (but not yet in Europe).

- Not relevant for TFC readers, but many are “single program title” FASTs—like a Baywatch or Australian MasterChef or Midsomer Murders type of channel.

The SmartTV (CTV)-run channels are a mix of all the above.

- Samsung already offers close to 100 free channels through Samsung TV Plus.

- Focused on high brand names, known partners, producers, and distributors, they see AVOD and FAST not just for library titles sitting on a shelf, but as a higher profile bigger window/destination.

- For example, in Germany they acquired the top new Das Boot series in 8K.

- They have O & O (owned and operated) dedicated channels of their own in 5 markets (Netherlands, Sweden, Germany, UK, Spain) but also the ‘single title’ bingeable branded channels (e.g., Baywatch) and curated entertainment hubs (e.g., comedy, entertainment, reality, lifestyle).

- Focused on high brand names, known partners, producers, and distributors, they see AVOD and FAST not just for library titles sitting on a shelf, but as a higher profile bigger window/destination.

- Xumo had earlier also crossed over to EU and also offers, via LG smart TVs, a FAST TV service with more than 190 channels available in France, UK , Germany, and Italy. Some include natural history, drama, or foreign language.

- Paramount’s Pluto TV (part of the ViacomCBS Inc., which is now Paramount Global), already a leader in the U.S. has been expanding aggressively through Europe. It’s just had its 10-year anniversary, apparently, with 70M overall monthly active users (MAU), over $1B in revenue last year, and by now has spread to 25 regions (including beyond US: UK, GAS [Germany Austria Switzerland], Spain, Italy, France, and, via its Viaplay partnership, the Nordics, and in Canada, via Corus, which launched in December 2022).

- They differentiate themselves from other types of FASTS as they are “pureplay” FAST (linear), not a free tv companion/AVOD ‘add on’ like others in the UK (Freevee, ITV, MY5). They already have 150 channels in the UK.

- In the UK, they focus on the opportunity arising from the 3M viewers who have zero linear connection (no free tv) and also an additional 10M who technically have a connection to Cable TV, but who don’t really ‘use’ it, so for them, FAST is the key opportunity to give those viewers a “linear-like” free experience, via CTV.

- In France, they have 100 channels, some focused on film and nonfiction.

- In Nordics, they already partnered with Viaplay SVOD, replacing the former free AVOD Viafree, and this is a model they want to continue in other regions.

Other AVODs but not FAST include:

- Amazon Freevee, formerly IMDb.tv – which just launched in the UK and Germany

- NBCU’s Peacock (part of Sky/Comcast group) launched in UK, GAS, and Italy as part of Sky partnership (subscription and ads angles, but not FAST channels) and some of its content will also follow the path of the new Comcast SVOD SkyShowtime SVOD which rolls out to 20+ EU regions that are not UK, Germany, Italy (so as to not compete with SKY PayTV subscription, not FAST channels).

Homegrown FAST Services in the EU

- The largest, Rakuten TV, for example, offers both TVOD, SVOD, AVOD, and FAST, with 12M viewers across the continent, 95% of them on connected television. Their emphasis is now mostly on AVOD/FAST.

- AVOD: 10,000+ titles (films, docs, series) from the U.S. and the EU/local indies, as well as Rakuten Stories (Originals and Exclusives). Movies here, for example, on the UK side.

- FAST: 90+ free linear channels from global networks, top EU broadcasters and media groups, and the platform’s own thematic channels with curated content (some movies and docs from indies, too).

- Currently in 43 EU regions including in Spain, Portugal, UK/Ireland, France, GAS, Italy, Sweden, Finland, Benelux, Croatia, Portugal,, reaching more than 110M households via SmartTVs/Apps.

- Some examples of channels of interest potentially to our readers include:

- In France WildSide Tv (an offshoot of Wildbunch sales agent style of films/docs, i.e. arthouse/festival) as well as Universcine (indie cinema and fest titles sourced worldwide). Both those FASTS also have SVOD counterparts that preceded the addition of the FAST, so windowing is important.

- Rakuten’s Zylo Emotion’L is a film channel aimed at women with a mix of romance, comedies, and thrillers, while Zylo’s Ciné Nanar Channel, is a new FAST channel dedicated to a mixture of nostalgic movies that focus on action, disaster, and creature movies in the fight and sci-fi/ fantasy realm.

- In Italy they have also added shorts, natural history, nature themed channels

Other EU Players

Beyond mainstreamer JOYN (JV ProSieben and Discovery, with limited opportunities for U.S. indies), there are other local regional smaller AVOD/FAST sites, such rlaxx.tv in Germany (indie movies, series, doc channels, among other genres and niches).

- WEDOTV: (UK/Germany) For indie movie producers/sellers, there’s a stronger appetite in niche content services such as WEDOTV (the late-2022 Rebrand of earlier AVODS WatchFree and Watch4Free) in UK/Germany (both AVOD and FAST). Italy will be added in 2023.

- Wedotv (which includes thematic niches (we do movies, we do docs, etc.) began as AVOD and it remains the mainstay of their service offering (90%), with FAST being used more as a promotional or discovery complementary offering.

- Wedotv is mainly for movies, also tv, and a new documentary channel, as well as more other recent genres.

- Their main focus is movies for AVOD, from all over the world, usually with some cast/distinguishing sales features/festival acclaim, socials. They “don’t need” Oscar winners, but candidate films should be capable of international region traction in terms of cast, theme or acclaim, if not readily recognizable.

- They are increasingly interested in other genres like factual, factual entertainment, and sports.

- They market the service simply as “free to air,” whether FAST or AVOD. Consumers don’t care, although they’d need both rights, respectively.

- After their earlier days of playlists, they now have a more “curated thoughtful approach to programming,” with categories and themes—for example, action night, thriller day, horror night, etc.

- MOJItv: (Benelux) FAST channel (carried on Samsung TV Plus and Rakuten—kids content only

- The Guardian FAST channel: (UK, EU) Launched in spring 2022 on Rakuten TV, it is the “first time The Guardian’s documentaries and videos will appear on a scheduled, linear channel as part of The Guardian’s global digital network.” (source).

Reach: the 43 Rakuten TV regions above (via Samsung, LG, and also via Samsung’s own FAST TV service Samsung TV Plus in select countries.) - SoReal (all3media’s lifestyle TV FAST)

- ITVX: (UK) Just launched in December 2022. SVOD with an AVOD tier and also 20 FAST channels in the UK, which they expect will make FAST more mainstream and help normalize the UK audience’s behavior, which was more traditional in terms of TV viewing and SVOD.

- However, most of the content on ITVX at launch is, predictably, from their own stable – thematic single program channels (such as Inspector Morse, Vera, ITV shows), also themes from their stable: crime drama, classic vintage films, sitcoms, reality formats, true crime), but…

- On the plus side there will also be some third-party content acquisition from indies selectively over time to round out the offering.

- LittleDotStudios: many AVOD channels including 7 FAST channels, many themes would be of interest for TFC viewers and they do buy from indies.

- FASTs: Real Stories, Timeline, Wonder, Real Crime, Real Wild, Real Life, and Don’t Tell the Bride

- For the other channels/YouTube and other AVOD activations, see these links (here and here) for multiple narrower themes you can match your titles with.

- They are actively buying from indies both direct and via sales agents, aggregators, core regions such as the UK, the U.S., other English regions, and then some EU regions, for example, Germany.

- Paying either rev share, MG plus rev share, or flat fees, film dependent – that’s the good news. The bad news is that lately they’re buying in packages of 50 or so titles, and phasing out the ‘’one-offs’’ from indies…but there can be some exceptions.

- TF1’s STREAM: (France) This service is part of myTF1, via Samsung: it offers multiple (40+) FAST/AVOD offering channels, aimed at the French market; some are IP (single title specific, regarding French titles on the broadcaster), while others more genre-led programming (such as archive movies, international dramas – mainly big names like Mad Men, French dramas, thriller, romance, manga/anime, for example).

Pragmatics

Sourcing Deal possibilities: How to reach the platforms?

The EU opportunity is growing in 2023 as opposed to the very overcrowded market in U.S. That’s the good news. But to manage expectations, the bulk of content sourcing by these larger FAST services is first from the content libraries of the studios, distributors, aggregators (as in the Part 1 AVOD blog).

There can be some exceptions for stellar one-offs, but it is easier for the platforms to deal with packages, volume and frequent “refresh.” The smaller niche services (like movies, horror, or LGBTQ+ specialized ones) you can approach directly with more ease.

- If dealing with sales agents, and/or aggregators, some are more active/savvy in this part of the digital sector (beyond the big global platforms) than others, such as Syndicado (Canada), OD MEDIA (Netherlands-based but in 10 regions and dealing with 200 platforms in TVOD, SVOD and now strong in AVOD/FASTS including FASTS of their own), First Hand Films (GAS) (sales agent for docs, social, gender issues, etc. but they are also active in digital and AVOD/FAST), and Abacus Media (UK), all of whom do activity in AVOD/FAST as well.

Age of Film/Windowing

- Films 3-8 years old, as I outlined in my previous TFC blog article on SVODs, were usually possible candidates for acquisition on a non-exclusive basis in the SVOD window for the SVOD platforms beyond the Big Globals. Films older than this fell nicely in the AVOD/FAST window.

- However, those lines are rapidly blurring, and now newer titles (for example, those that are 5 years old or even more current) can be picked up by an AVOD/FAST and occasionally exclusivity can be required. Therefore, it is critical to watch the windowing to avoid shooting yourself in the foot. As mentioned in part 1 of the AVOD blog, sometimes U.S. AVOD revenues can exceed those of SVOD, but that’s not yet the status in UK/EU, which is a few years behind, so this needs to be balanced carefully.

Slanting the pitch

- It is also essential to show [as mentioned in part 1 of the AVOD blog] some connection of your U.S. film to the EU platforms, for example, in theme, cast, IMDb and Rotten Tomatoes ratings, metrics (socials, audience engagement, clever marketing, or packaging/bundling) with other titles in similar category or theme or other hooks (like name cast in your film or elsewhere on the platforms).

- Generally, the overseas EU platforms need to prioritize their own EU originated producers and suppliers (also for content quotas that are express or implied, depending on the region), so it is a lot harder these days to sell a one-off from the U.S. over something originating from the EU.

- That said, U.S. indie content can still have appeal, and one can find other “hooks” to pitch, for example, when we helped producers from the U.S. sell music docs to the EU, we also indicated the massive fan bases of the rock/punk groups in the very regions of Europe where we were selling the film and added film festival or press reviews from those regions so the pitch was more tailored.

- What might be old to someone in the U.S. could be new to someone else in the EU, which is a double-edged sword–either an undiscovered gem that helps the platform differentiate itself, or a unsold film that was unsold for a reason. Handy to address this in the pitch, if relevant.

- Overall, each platform needs different types of content so find your match: niche subjects with traction indeed include paranormal, Sci-Fi, Black, LGBTQ+, action, adventure, horror, fast-paced docs (e.g., music/lifestyle, but also educational). The key is to match….

Basically, if you are able to go direct, or, if indirect, with the support of reps, then it is helpful to do as much as possible to “help do the buyer’s job for them”—and indicate where the film fits in their offerings, or suggest other titles they already have on their site that are comparable, etc.)

Deals

AVOD/FAST revenues: most platforms expect non-exclusive and via rev share, and only some titles are doing well on this basis, if standalone—it’s still early days in the EU.

Some platforms do pay a flat-fee (e.g., 5-figures per title, depending on regions). It helps you have some certainty but then again, they don’t have to share the viewership data/calculations, so to speak. Some of the various larger players are moving in this direction.

In cases of mid-sized or smaller platforms, one can choose, in some cases, not to take a flat fee, but a smaller minimum guarantee (M.G.) plus rev share, or take a larger ongoing rev share for upside (e.g., some platforms offer the indie film the choice). Its platform- and film-specific FAST is too new to have a locked-in model, so at least there is some room for negotiation with the mid-sized and theme/niche platforms overseas, where deals are not negotiable at all (again this depends on the platform and film).

Discovery helps increase ad revenues

- Outside of U.S., as with Part 1 of the AVOD blog, it is even more important when a sale is made (whether by you or your reps) on a AVOD rev share basis, to take steps to actively ensure you help audiences “find your film” on the AVODs/FASTs, so that it doesn’t sit unnoticed in a huge online store (and thus unmonetized).

The bottom line is that it’s important to be familiar with each platform and know how one might best match and search for your film. Pay attention to keywords, genres, formats, and topics actually used on the AVOD and FAST sites, not just the ones you had in metadata from earlier windows.

Wendy would like to note that much of the factual content from the above article was sourced and summarized from the following sources (articles and podcasts):

Articles

WTF are Fast channels (and should advertisers care)? (The Drum, November 25, 2022)

Why Haven’t FAST Services Taken Off in Europe? (Videoweek, April 26, 2021)

La FAST TV accélère en Europe (JDN, March 11, 2022)

FAST channels: The New Grail of Connected TV (Onemip, July 25, 2022)

Ad-Supported Content Will Benefit from Streaming Subscription Overload (SpotX, Sept. 2, 2020)

Samsung TV Plus launched new channels across Europe (Prensario, Oct. 18, 2022)

Samsung TV Plus: AVOD pioneer seeks content partners in Cannes (Onemip, Oct. 14, 2022)

Rakuten TV expands FAST offering in Europe with 21 new channels (Digital TV Europe, Nov. 18, 2021)

The State of European FAST (Variety, Dec. 23, 2022)

Free, Ad-Supported Television Is Catching On FAST: Boosters Hail It As Second Coming Of Cable, But Just How Big Is Its Upside? (Deadline, Dec. 14, 2022)

The Meteoric Rise of Free Streaming Channels: A Special Report (Variety, Dec. 1, 2022)

Podcasts

Samsung on the FAST and AVOD environment | Inside Content Podcast (3Vision, May 4, 2022)

wedotv on the growth of FAST, innovating distribution strategies and harnessing opportunity | Inside Content(3Vision, Dec. 15, 2022)

The Best of FAST with All3Media, Paramount UK and Samsung | Inside Content (3Vision, Nov. 9, 2022)

Orly Ravid December 31st, 2022

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms

All About AVOD? part 1: What To Do with Your Library Title

by David Averbach and Orly Ravid

One of the joys of working at The Film Collaborative is our extended filmmaker family. Some of the filmmakers we work with we have known for decades, back to when they made their first films. Inevitably, after seven-, ten-, or twelve-year terms, many of these filmmakers are getting their rights back from the distributors with whom they originally entered distribution deals.

They often ask us, “What is possible for my film now? What can I do to give it a second life?”

(We should state that the vast majority of these filmmakers do not have obviously commercial projects that could simply be offered to a different large streaming service like Netflix or Hulu. They are the type of films that TFC handles: solid films with good or at least decent festival pedigrees and proper distribution at the time of their initial release.)

Unfortunately, there is no one answer for every film. Nor is there a fixed answer for each type of film, as platforms’ needs can change at the drop of a hat. Except that all platforms seem to have an endless appetite for true crime docs, but we digress…

So, this blog article is less of a “how to” for library titles, and more of a “how to think” about them.

Certainly, there are non-exclusive subscription-based (SVOD) platforms that align with various content areas, such as Documentary+, Topic, Wondrium, Curiosity Stream, Coda, Qello, Tastemade, Gaia, Revry, and many more (check out our Digital Distribution Guide for more info). These are platforms that offer a revenue share based on minutes watched. Since they may have not been in existence when the filmmakers’ original distribution deals were arranged, they are definitely worth exploring when one (or more) of them is a fit for your project.

But there are also ad-supported (AVOD) platforms1, which are free to the end user and rely on commercials that play before the film starts. Generally speaking, AVOD platforms seem to be more lucrative in terms of revenue than specialized SVOD platforms, and we’ve heard that some films are making “real” money them (more on that later). While there’s no guarantee that AVOD platforms will bring in more money than SVOD platforms, or much money at all, this at least makes sense, anecdotally: with the rise in commercial streaming services and especially since the start of the pandemic, folks are watching increasingly more content, but actually spending less above and beyond the Netflix/Amazon Prime/HBO/Disney etc. combination of platforms that they have ostensibly come to view as basic utilities.2 So AVOD provides a win-win for platforms and consumers alike.

Until recently, filmmakers have been somewhat reluctant to place their films on AVOD platforms, but they are coming to realize what distributors have known for a few years now—that AVOD can continue to bring in revenue when transactional platforms such as iTunes are no longer performing for a film the way they might have at the beginning of their digital run.

So, we set out to ask what we believed was a simple question: which AVOD platforms are taking which type of library content? The Film Collaborative has some limited experience with AVOD platforms, but we felt it prudent to talk to some folks that do this day in and day out. To that end, we reached out to Nick Savva, Vice President of Content Distribution at Giant Pictures, and Tristan Gregson, Director of Licensing & Distribution at BitMAX.

The answer turns out to be a complicated one. Here’s why:

Most AVOD platforms are looking for all kinds of content. One of the trends that has been occurring for the past few years is the addition of new platforms, not just in the U.S., but globally. And the pandemic has accelerated existing trends, so there are even more new platforms than ever. These platforms are not going to be able to produce or acquire enough new content to justify their existence, so they rely on library titles as much as they do new releases. So, the good news is that there are more outlets and revenue opportunities for library titles than ever.

The not-so-great news is that sometimes AVOD platforms are actually looking for specific types of films, but only for a limited time to fill a specific need. Platforms have a good sense of what percentage of their films are, for example, comedies, dramas, thrillers, horror, documentaries, true crime, etc. When they look at who is watching what, if comedies are overperforming on the platform relative to the percentage of titles they occupy overall, the platform may not take as many comedies for a while until that changes, or they could decide to double down and take more comedies at the expense of other types of films. Conversely, if there is a category that is underperforming, they could decide that they need some fresh meat in that category, or simply decide to take less of it.3

So why exactly is this bad news? Because as the needs of AVOD platforms ebb and flow, the entities with the best chance of succeeding are those that can respond quickly to calls from these platforms for specific content. A high percentage of the work Giant Pictures does with AVOD platforms involves their distributor clients, who use Giant as a sort of white label service. Giant is tasked with placing their content libraries on these platforms because these distributors don’t have the bandwidth to keep up with which platforms want what from month to month. Similarly, BitMAX works with many studios to deliver to these platforms, but the studios are the ones handling the licensing. What this means is that the bulk of content going to AVOD platforms is coming from the content libraries of studios and distributors. That is not to say that films from individual filmmakers aren’t being placed on AVOD platforms by Giant/BitMAX, it’s just that studios and distributors are their go-to sources for content because they can provide a bunch of titles with a quick turnaround.

The sad reality here is that AVOD is one area of distribution where middlemen are being added to the mix in a way that makes it harder for individual filmmakers to take back control of their films.

Many of the filmmakers who have just gotten their rights back often remark to us how glad they are to have done so, as if they are finally getting out of a bad marriage. Even if the relationship wasn’t such a badmarriage, this sentiment—justified or not—perhaps stems from the fact that their TVOD sales had dropped over the years and they felt like their distributor was no longer doing anything for their film, or that they were tired of not receiving reporting because there were long periods of time with no earnings. The last thing they appear to want to do is start up a new relationship with a new distributor or aggregator and incur more encoding costs for a shot in the dark in terms of being accepted by these platforms only to earn $12 a quarter in earnings.

It’s important to really have a look at the reporting your old distributor provided you. There’s a good chance that simply re-creating what your old distributor did—perhaps your film was already on AVOD platforms—is going to give you a completely different outcome. But to the extent that your project has not been tested in the current landscape, what should a filmmaker be thinking about if they find themselves in the position of deciding whether to go it alone or offer their film to another distributor?

It’s Your Time and Money

Bandwidth:

Tristan Gregson remarked that the same rules apply for library titles as when just starting out, and his stance was the following: if you know how to engage your audience then put it somewhere. If not, then don’t. Whether you try to go it on your own or partner with another distributor, unless there is someone that’s going to remind your audience that it’s there, there’s a good chance your film will sit unnoticed in a glut of content. This is going to take some effort and while a new distributor might do a bit of marketing, you are going to have to get creative. Perhaps time the re-release of this older film with a new project of yours?

Cost:

If you go through an aggregator like BitMAX, you are probably looking at a bare minimum of $2,000 for encoding, QC, and delivery and to pitch and deliver to a few SVOD or AVOD platforms. It’s a fee for service, so they will be hands off when it comes to strategy, and uninvolved when it comes to your earnings. If a distributor like Giant Pictures is willing to work with you, it can cost twice that much, but they will be real partners in the sense that they will be proactive in helping you come up with a strategy. They will also take a certain percentage of your earnings. You may also be able to negotiate lower encoding costs in exchange for an increased percentage of your earnings.

What is in it for the Platform?

Metrics:

Nick Savva advises filmmakers to think about your film like a platform would: what are your film’s metrics? These scores can tell a lot about the public’s level of familiarity with your film, and there are data tracking services that distributors and platforms use to determine them. Also among the first things that an acquisitions team would look at would be indications of basic audience awareness, such as the of the number of positive reviews on Amazon, or the ratings on IMDb. If the metrics are good, a deal might be attractive to a platform. Are there any recent reviews? In other words, does your film still hold up?

Is there one Platform that is better for my film than others?

Honestly, there are not all that many AVOD platforms in the U.S. Tubi, Pluto, Roku, Peacock, IMDb TV, and a few others. The good thing about AVOD is that most deals are non-exclusive, meaning that you can be on more than one at once. But should you apply for all of them? How does one decide?

Signal Boost:

The following might not be possible for every film, but, if possible, try to think about the likely television habits of your audience and the specifics of each platform and take advantage of the free signal boost.

People are very familiar with platforms like Netflix and Hulu, but when it comes to platforms like Tubi or Pluto, why would one choose to watch one over the other? The answer might be simpler than you would think!

Does your film have a TV star in it? If they are on the FOX network, chances are that audiences will see ads for Tubi, because Fox is the parent company of Tubi. If they are on NBC, then perhaps Peacock or Xumo will be advertised.

There are also tricks that might apply for documentaries too. Pluto just became available in Latin America and Mexico, so films with Latinx content might want to consider that platform first.

One of The Film Collaborative’s digital distribution titles, The Green Girl, has been doing extremely well on Pluto, but not so well on Tubi or Roku, and for the longest time we couldn’t figure out why. Then it hit us: this documentary is about an actress who famously appeared on the 1960s television show Star Trek. Since Pluto is owned by Viacom, which is the parent company of Paramount, Pluto is the AVOD destination platform for Trekkies!

Keywords:

Make sure your keyword game is strong. Aggregators and distributors will ask you to fill out a metadata sheet with genres/keywords, but you must make sure the choices conform to actual categories and genres on the platforms, which can differ from one another and evolve over time. Distributors have even admitted that it’s hard for them to keep up sometimes, especially if such metadata is capture via web interface. Case in point: The Film Collaborative placed a few films we have been working with for years onto Tubi, but the keywords that we chose when we first submitted the film to our aggregator were based on iTunes genres, which are very narrow. Cut to the films getting up onto Tubi, and they were almost impossible to find without searching for their exact titles. It’s been several months, and we are still struggling, with the help of our aggregator, to get these updated on the platform. Bottom line is that it’s important to be familiar with each platform and know how one might best search for your film and be proactive to ensure that the proper information is being delivered to each platform at the time of delivery.

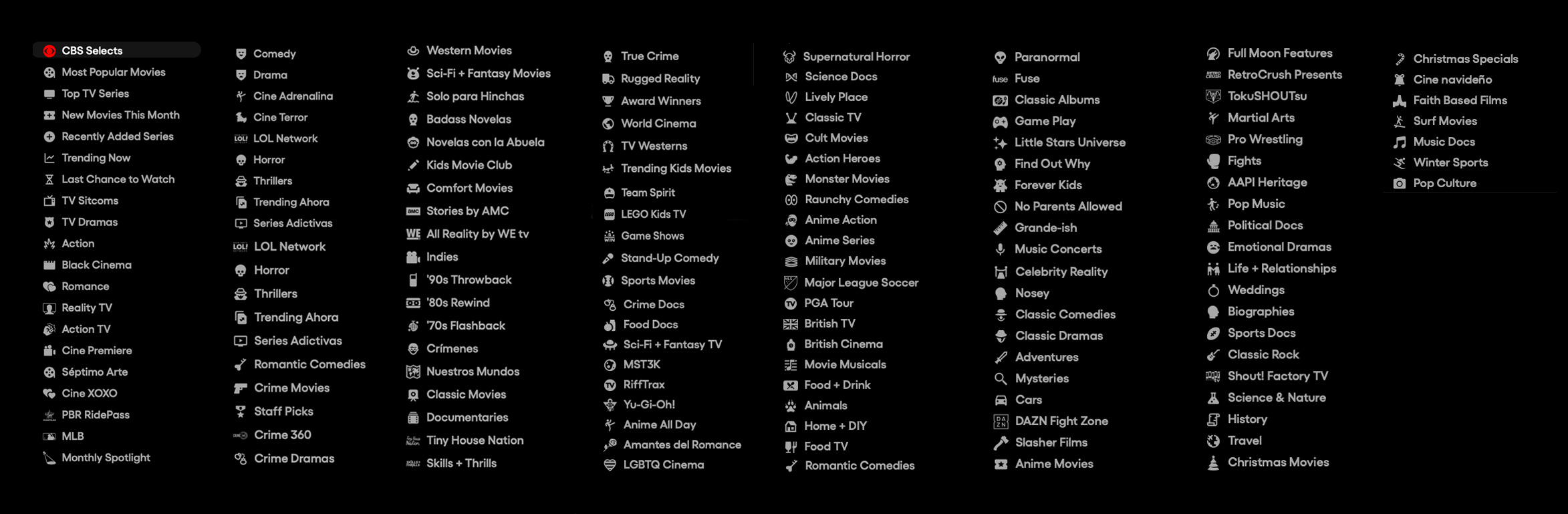

Pluto TV (owned by CBS/Viacom) offers a dizzying array of genres/categories to choose from (they appear in a vertical sidebar and seem to rearrange themselves periodically)

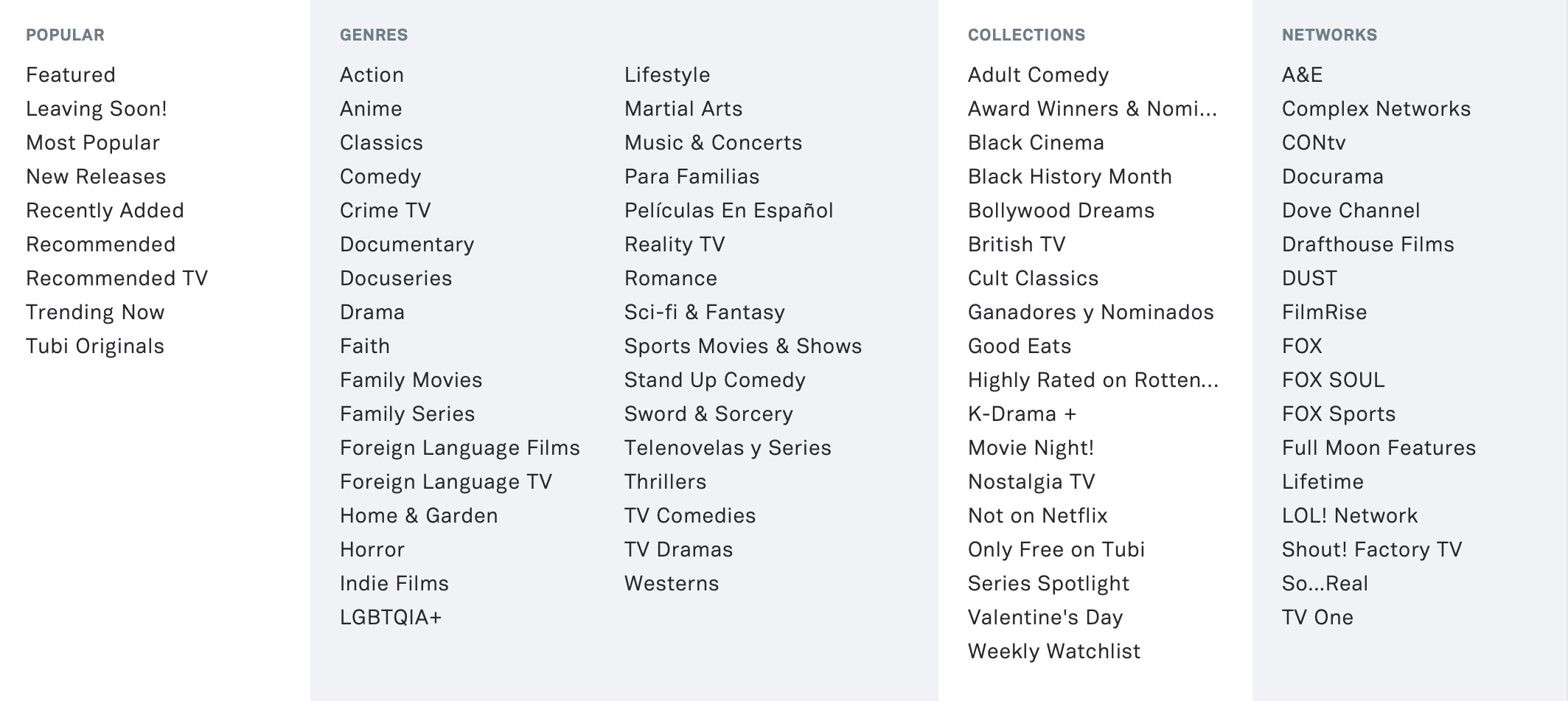

Tubi’s current “Browse” navigation tab. Tubi’s parent company is Fox Corporation.

Very Mini Library Titles Case Study

We talked to director/producer Kim Furst, whose rights to her 2014 film Flying the Feathered Edge: The Bob Hoover Project came back to her after her aggregator (Juice) declined to renew the term. She expressed that she did not want to use another aggregator like Distribber/Quiver/Bitmax/FilmHub because there was a concern that they might not be around in another 5 years. (As you probably are aware, Distribber has shuttered, and Quiver is not currently accepting films from individual filmmakers and will probably turn into something else).

So, she went with Giant Pictures.

The cost to re-encode was about $4K. While she did not feel great about having to shell out such a huge chunk of cash on a library title, Kim still felt that the film still had life in it, and she wanted to try other distribution avenues, such as public television, that she never managed to do when the film originally came out.

We should note that one of the reasons why Giant might have been interested in the film was that it is narrated by Harrison Ford. The film is about Bob Hoover, an American fighter pilot and air show aviator, and Ford has a longstanding love of flying planes. So, there is some commercial appeal that can be leveraged here.

She is at the stage where they have initiated the re-release. Right now, the film is back up on TVOD platforms, including being re-placed on Amazon, which Giant was able to accomplish despite the platform’s embargo on unsolicited non-fiction content.

We asked Kim to report back on what happens next. We suggested that she note where all of Harrison Ford’s top movies are on AVOD and take note if that platform sees any boost from the connection.

Revenue Range

With so many variables and permutations, it’s hard to give a real range in terms of what’s possible for a library title on AVOD, especially since it’s impossible to know when we are talking about the revenue of a “library” title—as opposed to that of a title that enters AVOD as part of their “new release” window.