You Plan an Impact Campaign…and the Heavens Laugh

February 17, 2025

Peggy Callahan is the co-director and producer of Mission: JOY – Finding Happiness in Troubled Times

I have been a human rights activist practically since birth, having been raised by a Canadian single mother in the South of the U.S. She was a vocal supporter of the civil rights movement and most of our neighbors…were not. My mom made sure I knew that the discrimination going on was “unmitigated bullshit,” in her delicate words. I grew up seeing human rights activists as the biggest heroes, and I wanted to do my part. Over the years, people like the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Tutu were guiding lights for me, especially as I started out with a career as an on-air journalist, a national news executive, and then as a documentary film producer/director. I always found ways to weave in stories about social justice.

In 1999, while I was contemplating my next documentary, I read the very first book about modern slavery and human trafficking and it made me stop cold. By that point, I had won a bunch of awards for the social justice stories I had told, so my first thought was to make a documentary about modern slavery and human trafficking, and I imagined I would speak with the author of that book, and we would get to work on it. But I realized that this issue was so huge and so hidden at that time that it needed more than a documentary. It needed a movement. So instead of asking that author, Kevin Bales, to collaborate on a documentary, I asked him to collaborate on building the modern anti-slavery movement in the U.S.

In 2000, Kevin and Jolene Smith and I started the first organization in the U.S. dedicated to ending slavery globally. Archbishop Tutu was on our International Advisory Board, and he also presented at the Freedom Awards that I produced, so we had worked in the same orbit for years.

From Book to Film

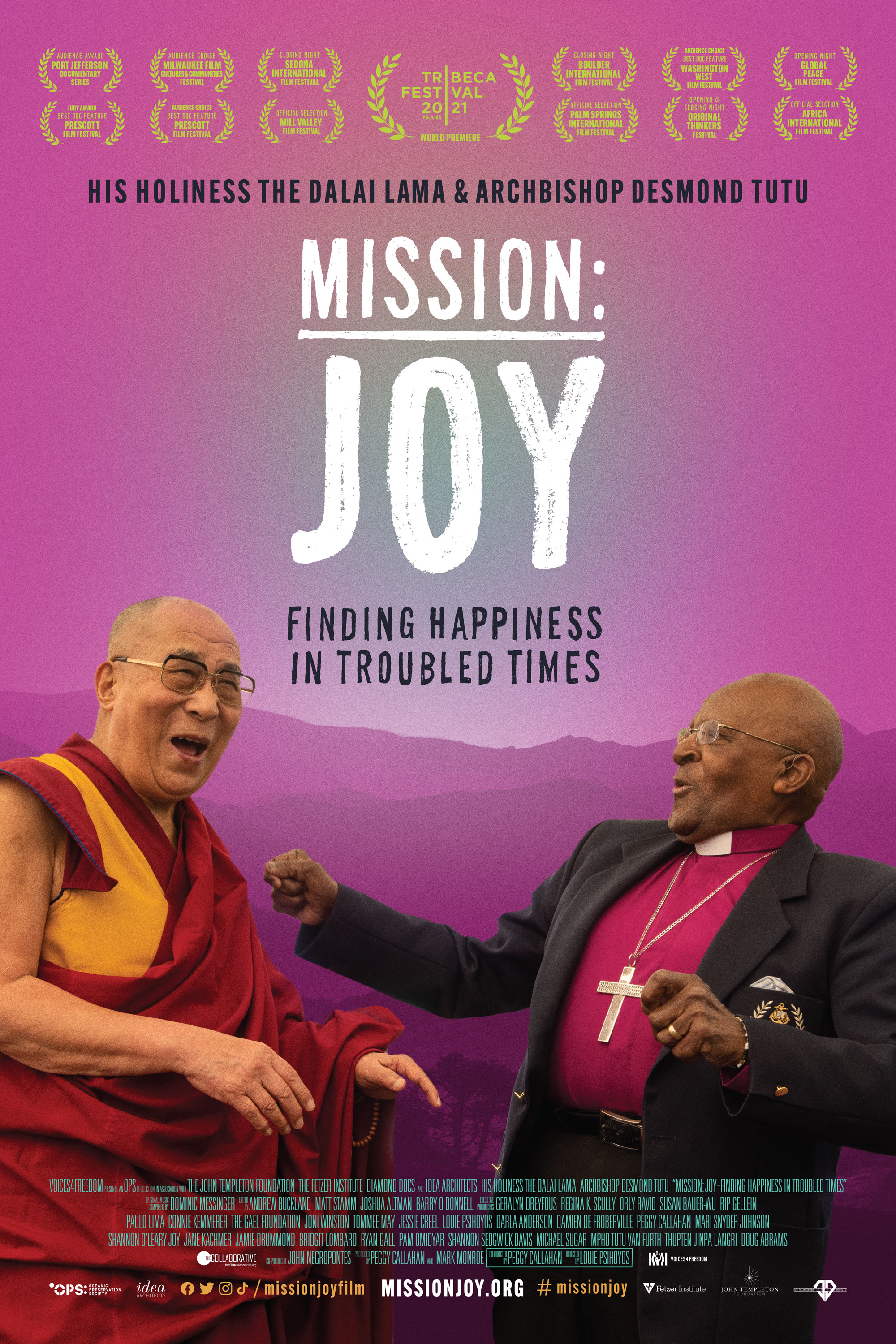

My involvement with Mission: JOY, featuring two of the most renowned, wise, and funny men on the planet, His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the Archbishop Desmond Tutu, originally began not with the idea to do a film—it was to support the book, The Book of Joy, written by my dear friend Doug Abrams. The book eventually came out in 2016, but in 2015 Doug asked if I would come document the conversations that they were having. The footage was intended to help Doug write the book and then promote the book when it was published—for example, what their expressions looked like when they were saying things, having all the transcripts, etc. So, over the course of five days, I directed a five camera shoot at the Dalai Lama’s compound in Dharamshala, India. It is up in the foothills of the Himalayas, this really beautiful mountainous setting—which is really far from everywhere. It took a truck 12 hours to get the additional equipment we needed to Dharamshala. We crossed our fingers, toes, and eyes that we hadn’t left anything we needed off the list.

I was initially just there to support the book, but, while on set, we experienced how wise, tender, and laugh-out-loud funny they were together. “Hmmmm,” I thought, “maybe their inspiring conversations could be the backbone of a film.” But there was not even a free minute to discuss anything like that. They had to complete the book within a certain window of time, and it was fast approaching. It was clear that if there were to be a film, I’d need to go back later and have the conversations and get agreements about rights, etc. At the time, they simply needed a filmmaker they trusted who could be invited into the Dalai Lama’s inner sanctum, even his private meditation room. There wasn’t time to discuss anything beyond that.

I almost missed catching the vision of how the film could work. For one, I was leading an anti-slavery organization. People’s lives are at stake, it deserves a lot of time and attention, so there was of course a big pull to leave well enough alone with the Joy project. I was grateful to help with a project that the world really needed. Doug Abrams and the Holy Men created an inspiring international best seller. So, on the one hand I could feel satisfied with that. Done and done.

But something told me it wasn’t “done.” For a month straight, I spent every spare minute watching and re-watching all the footage we had shot. I turned it over and over in my mind about how I could tell that story. I knew it couldn’t just be a “good” documentary. There were already a lot of documentaries about those two men. If I was going to take years of my life to do this, I had to do their joy story justice. And it had to be fun to watch—and they’re honestly funny, which is surprising to most people. I knew that if people weren’t laughing and inspired when they watched this movie, I wasn’t doing it right. But damn, that was going to be a high bar, and I needed to be sure I could make it happen.

Getting the Rights and Building a Team

After I made the decision to go for it, I was raring to go… but then it took two years of creative problem-solving to get all the permissions secured. You could call it a gut check, maybe. I had to really want to do this film.

And from the beginning, this was not just a film. In fact, we originally thought we’d start with a “We Are the World”-type charity single to help usher in the concept. And Arch and the Dalai Lama said that if we were going to do a film, it needed to be shared not just in the Global North, but in the Global South as well. And as sacrilegious as it may sound to filmmakers, people watching the movie was not the men’s highest priority. Their highest priority about the entire initiative was for people to learn the how-to of joy, and to practice creating joy in their own lives. So, our impact campaign had to get that practical. It couldn’t only be about maximizing the number of people who watch the film. It was a lot to commit to.

We formed a Brain Trust, comprised of Orly Ravid, Doug Abrams, funders, and Darla Anderson—who now works at Netflix but formerly a producer at Pixar Animation Studios, where she produced 2 Academy Award-winning films, Toy Story 3 (2010) and Coco (2017). We met every 6 weeks and brought in activists and people from all over who had experience working on docs because we knew we were going to have to raise a lot of money and wanted insights.

Even after we had all agreed on this more expansive concept, we still had to dot all the i’s. That’s where Jay Gendron and the Southwestern Law School Arts Legal Clinic came in. First, Jay began helping me through the clinic, then Orly Ravid started helping, too, with the legal work. (Orly, in addition to being The Film Collaborative’s Founder and Co-Executive Director, is an Associate Dean at the Donald E. Biederman Entertainment and Media Law Institute and an Associate Professor of Law at Southwestern and now runs the legal clinic). For a while it was bureaucratically held up, which was a pain the ass for everyone involved. Orly and Jay made it is less so, that’s for sure. But there were so many unforeseen legal and other hiccups that Tutu used to tease, saying, “I hope the movie is done while I’m still on this side of the grass!” (He was battling a recurrence of cancer at the time.)

Arch and the Dalai Lama’s mission deserved the best people in the world, who were also fully dedicated to the mission. That was our standard. We brought on some amazing people. A few of them were so inspired by His Holiness and Archbishop Tutu that they volunteered their time and talents. There were four with major awards like Oscars and Emmys:

Louis Psihoyos came on as Director and contributed his experience exemplified by the Academy Award he won for The Cove (2009).

Darla Anderson and Damien de Froberville shared their mastery as they guided the animation for the film. This was important because we needed to tell the story of each man’s childhood, but there was no film footage of Arch as a child. None. We wanted to tell both of their background stories with equal care. As I mentioned above, Darla has won two Academy awards for Toy Story 3 and Coco. Damien is well known around the world for his work in animation and games. He has led units at Netflix, Paramount, and DreamWorks.

Mark Monroe is a renowned writer for award winning documentaries including Icarus (2017), The Cove, and Before the Flood (2016), among many others.

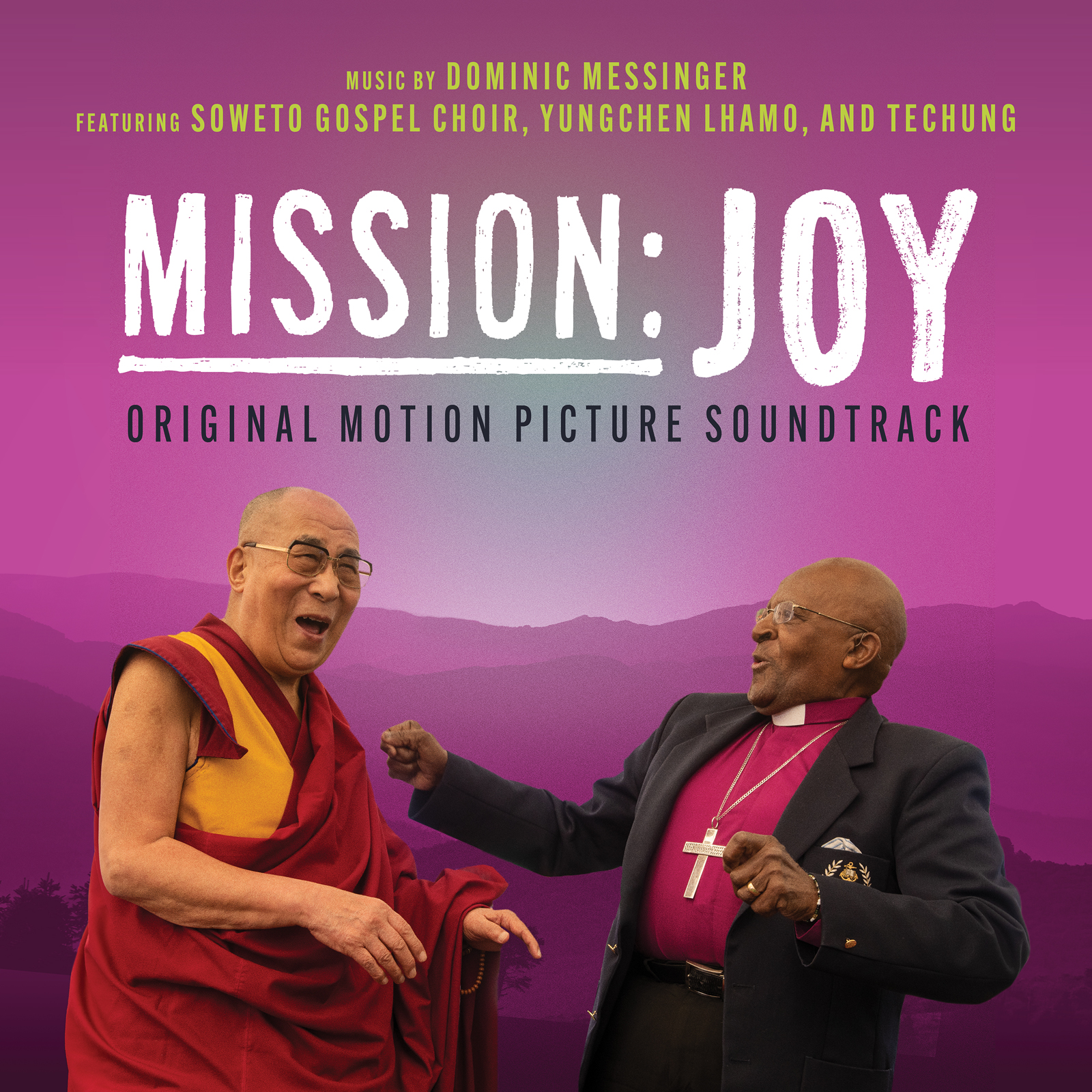

Dominic Messinger was determined to create music that captured the Holy Men and their cultures. He worked with artists from five continents. Dominic has won 14 Emmys for his work.

We did the audio at Skywalker Sound in Marin. They were top-notch. They still call and ask if they can help us in any way. Such dedication. The Film Collaborative came on board to manage the film festival distribution and fiscal sponsorship, and they knocked it out of the park. We tapped ROCO to handle all community screenings globally, which was a godsend, and to lead educational distribution and distribution outside the U.S. HelpGood managed our social media efforts, famously setting aside their own New Year’s Eve plans so they could launch our campaign as soon as possible. In each of those cases, their skills were superlative and their dedication to the mission was palpable.

I brought in John Negropontes as Co-Producer right away. I’d known him for years and knew what a talented producer and hard worker he is. He delivers 100% of the time, 100% on time. I asked Jolene Smith to be Impact Producer. She and I had worked together on global anti-slavery programs for 20 years, and we bonded over our love for audacious goals and pushing the envelope regarding what’s considered possible. She hadn’t worked in the film world before, but she’d designed and run global advocacy initiatives for decades, and I knew she would bring fresh thinking to the universe of impact campaigns, and we would delight in innovating together.

Fundraising Plan and Revenue Model

When I agreed to carry out the Dalai Lama’s and Tutu’s impact goals with the film, it meant that I couldn’t put myself in a situation where distribution was dictated by a for-profit company. It probably would have been a hell of a lot easier and faster to get for-profit funding, make the movie, and let them handle distribution. But the odds of a for-profit company prioritizing getting the film to audiences who couldn’t afford a movie ticket, or a streaming service, were unlikely, even before getting to the in-real-life impact goals we had. I couldn’t take that chance.

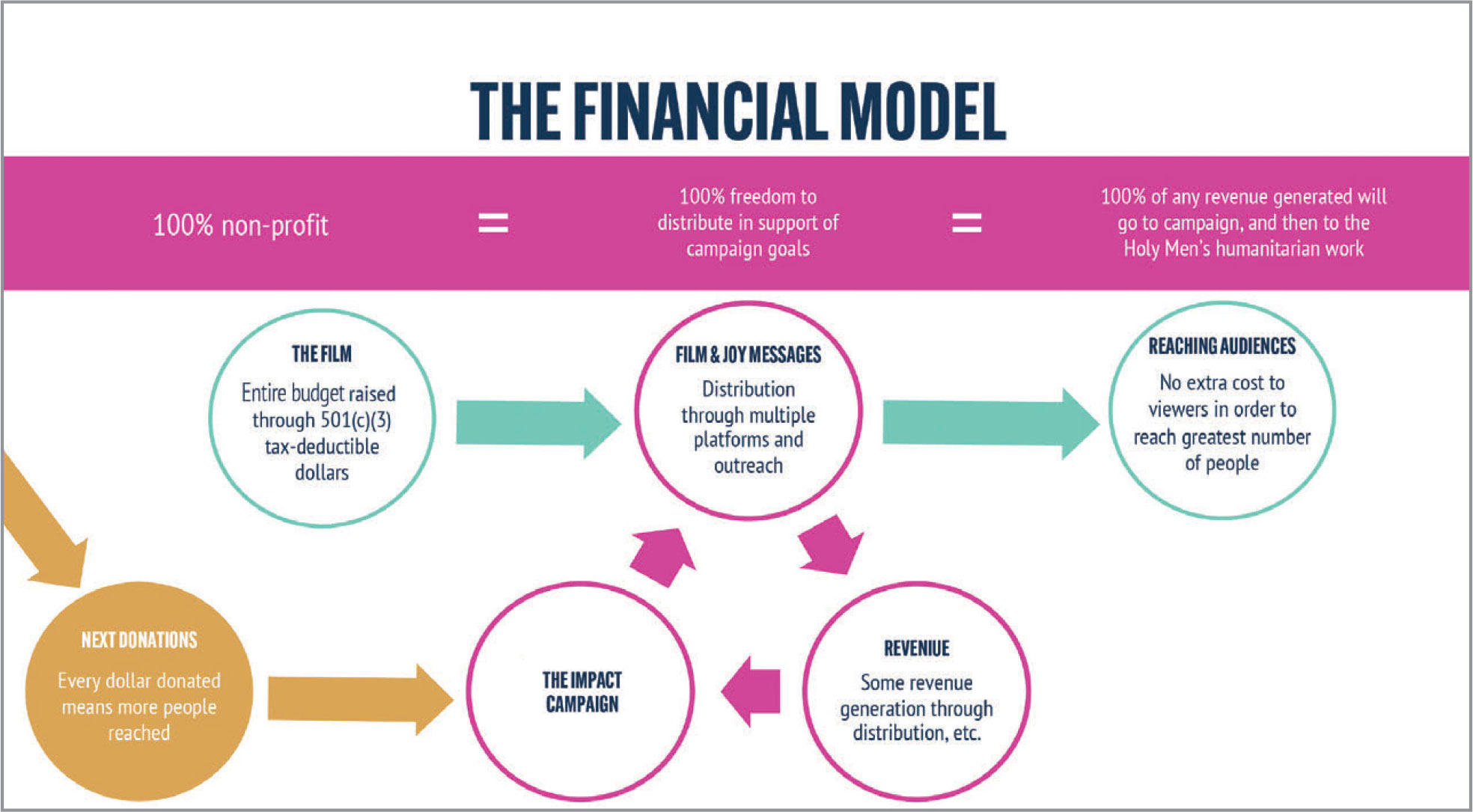

So, we decided to take no for-profit funding whatsoever. We raised the entire budget with nonprofit donations. That meant that I retained full control of the rights and could accept the distribution opportunities that were consonant with the impact goals of the holy men, and say “no, thank you” to the rest. Raising nonprofit dollars took longer than the alternative, but it was worth it to have full control to maximize impact.

In the long run, The Film Collaborative made it possible as our fiscal sponsor. The idea was that the nonprofit funding would cover the filmmaking costs, and then, when we said yes to the just-right distribution deal, we would use the payment from that to cover the costs of the impact campaign.

We crafted what we called an “Impact-First Revenue Model,” which prioritized our impact goals above all else and ensured that every dollar raised or earned was plowed right back into impact. It also ensured that we were never beholden to someone else’s profit motive when making decisions about distribution. For example, we included carve-outs in every contract we signed, so that we could continue to offer free screenings to community groups, prisons, etc., including online for millions of people. That scared off some distribution partners but ultimately allowed us to reach more vulnerable and marginalized people than we otherwise would have.

Pre-Selling the Film

That’s when I was working even more with Orly, who was advising us on distribution. We had William Morris Endeavor (WME, at the time the largest talent agency in the world) as the sales agent. And then we all started pitching everybody and their mother. Orly, Doug Abrams, and WME were pitching with us. And WME was sure in a red-hot second that we were going to get all the money we needed for the impact campaign. And when the impact campaign raised awareness about the how to increase your joy, it would also tell people about the film, some of whom would pay to see the movie, and that revenue would go back into the impact campaign, too. We thought we had it all planned. Win-win-win-win.

As we met with our best-case potential buyers, they would say, “We love this, we love this. This is perfect for us.” They were seeing it as we saw it: here are two people who have been to hell and back a few times—and even had a condo there for a while—and they figured out how to still experience joy. And this was at a time when the depression rates were at what was called a “double tsunami” in the world, so everyone was searching for accessible ways, such as this film, to help the many people who were hurting. I can still remember what they said the minute we would finish pitching: “Oh my goodness, this is the film for The Times, and you have these two guys who are screamingly funny and very wise. This is exactly what we need.”

But then later they would come back and say, “I’m sorry, I’m so sorry… we’re not going to be able to take it. We can’t.” And give no more explanation with that. After the third, fourth, and fifth most likely buyers all said the same thing, it was clear that something unsaid was at play. We heard through back channels that they believed saying yes to Mission: JOY would’ve put some of their other projects at risk—specifically the ones that get sold in China. One misstep and they could be blackballed.

What was little-known outside the industry at the time was that China was generating more than 1.5 times as much revenue the U.S. film industry (a trend which has since shifted). That turned some things on their heads. Film executives were starting to get their minds around what being shunned by the Chinese market could mean for their businesses. They were scared. We had gotten a taste of this when we were looking into creating the “We Are the World”- type charity single. We were reminded that some artists, like Lady Gaga, who was banned in China in 2016 after briefly meeting with the Dalai Lama. But we hadn’t accounted for the wave of self-censorship, probably before China had even weighed in that heavily, and our film was one of the casualties. We never discussed this publicly at the time, because why perpetuate the negative? But it was exasperating. We had this film that everybody agreed the world needed, and yet nobody from the industry felt they could be a part of it. It felt like a colossal waste.

But, with the mandate from the holy men to get the film and its messages out to as many people as possible, in all corners of the globe, I realized that we best get on with it. If the big dogs were not going to come on board, we weren’t going to sit around and cry about it. There were people who needed help, and we wanted to do our part to try to reach them.

This was one of those moments when our mettle was tested. With a combination of the pandemic and the self-censorship, we were going to get nowhere fast unless we tried things that were completely new. The traditional methods of getting a film out into the world were going to have limited impact in our case—at least at the beginning. It became our job to think expansively about the many ways we could get the film and its messages out.

Impact campaign

Since there were no distribution deals to hammer out at that time, we turned our full focus to the impact campaign. We had always conceived of it as something much broader than simply maximizing the number of people who see the film—but now we had additional reasons to lean in even more completely. If a large company was not going to take on the film and distribute it through their global network, then we were going to have to do it our own damn selves.

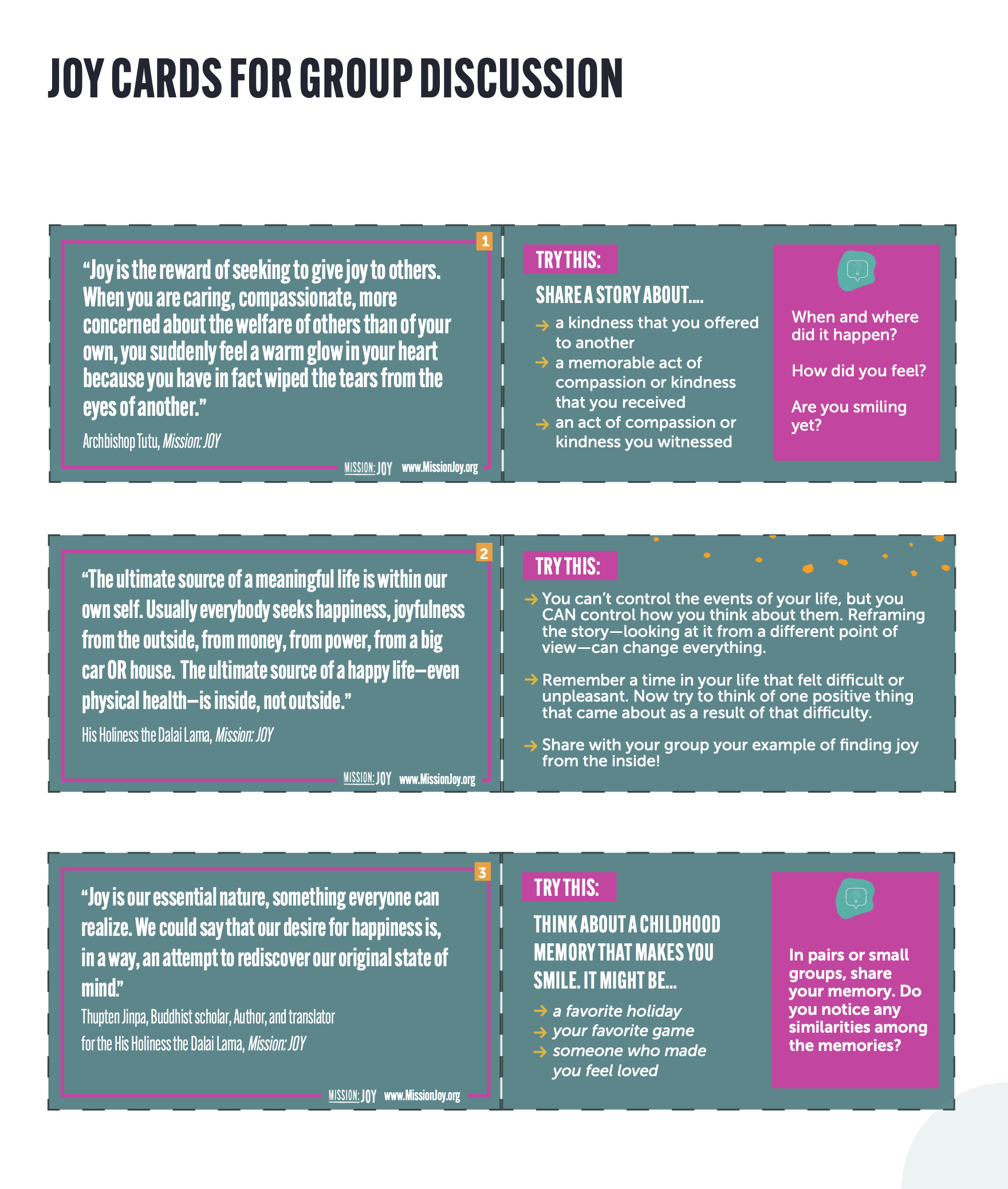

Here's part of a screenshot from our Impact Deck from July 2021.

While the making of the film was seen as its own standalone project, just like the book years before, the distribution of the film was part of this larger website and impact campaign. Here’s another graphic from the 2021 deck to expain what other components were envisioned as part of the impact:

In many ways, it was the Tale of Two Impact Campaigns:

- The “safe” impact campaign. The components that we had planned to do all along and could roll out immediately without risking any future distribution deals.

- The… shall we say… “courageous” (or maybe crazy) impact campaign. This included the components that we had to make up on the fly, many of which hadn’t been tried before and flew in the face of that standard way of doing things. It involved helping a lot of people see the movie for free. That was not cool with some potential distribution partners, who feared this would cut into their market. Which was where the need for courage came in.

The “Safe” Impact campaign

Film festivals

While we figured out an end-run around the major distributors, we could still continue with a film festival effort. We were thrilled that The Film Collaborative managed film festival outreach for the film and they did a great job. In fact, we’re still receiving requests to show the film as opening night or closing night of film festivals around the world. People seem to love it as a bookend, to set the tone, or to end on a unifying note.

We got the film done in one year and a week, starting in June 2020 and completing in June 2021—just in time for its premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival. Right during the pandemic. In 2021, Tribeca was the first major film festival in the U.S. to be held in person since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Things still felt a bit weird at that time. The premiere was hybrid. It didn’t include the kind of media coverage that it typically does. Was the premiere all that we had hoped for? No. But that wasn’t going to stop us.

So far, the film has been featured in 67 film festivals. A complete list of bookings from 2021-2024 can be found in this Airtable chart.

You can see some of the festival laurels and awards we received in the following graphic:

Educational Distribution and Community Screenings

ROCO handled our Educational Distribution. Schools and universities from South Africa to Malaysia screened the film in their classrooms. Just one of their screening events that was organized through university libraries reached 6000+ students and faculty globally. ROCO made the film available in prisons across the U.S., reaching 40,000 incarcerated learners. Watch the panel conversation they sponsored on October 6, 2021.

Some other screenings of note include during the COP26 conference in Glasgow, the Natural History Museum and the New York Times climate hub screened the film as a way to give hope and energy to climate activists. TED Women screened the film as part of their annual conference and film co-director and producer, Peggy Callahan, led a discovery session at TED Women Presents with Elissa Epel, PhD.

In all, working together with ROCO, more than 500,000 people saw the film for free through these efforts, many of those people from communities that cannot afford a movie ticket or a streaming subscription.

Viewers guide

We created downloadable Viewing Guide PDF of suggested activities to contextualize and prepare for the film, and connect and share afterward, with additional JOY resources. This was free on our web site and was also sent out to each host who organized a screening in their community, so that we did some of the heavy lifting for them. We wanted them to be able to just plug and play, knowing they had their own busy lives to attend to.

Soundtrack

We packaged the soundtrack to Mission: Joy with original music by multi-award-winning composer Dominic Messinger, which includes performances from iconic Tibetan singers and musicians @Techung and Yungchen Lhamo; the famed, official Soweto Gospel Choir in South Africa; and the F.A.M.E.S Studio Orchestra in Macedonia. Dominic was so meticulous in music selection that every time period you experience in the film is matched to music that was popular during that period, in that specific region of Tibet or South Africa, and performed on the local instruments that were typical at that specific time and place. It’s breathtaking. You can hear an interview with Dominic discussing what was most important to him when creating the soundtrack to the film, and the hardest lesson he had to learn.

Social media campaign

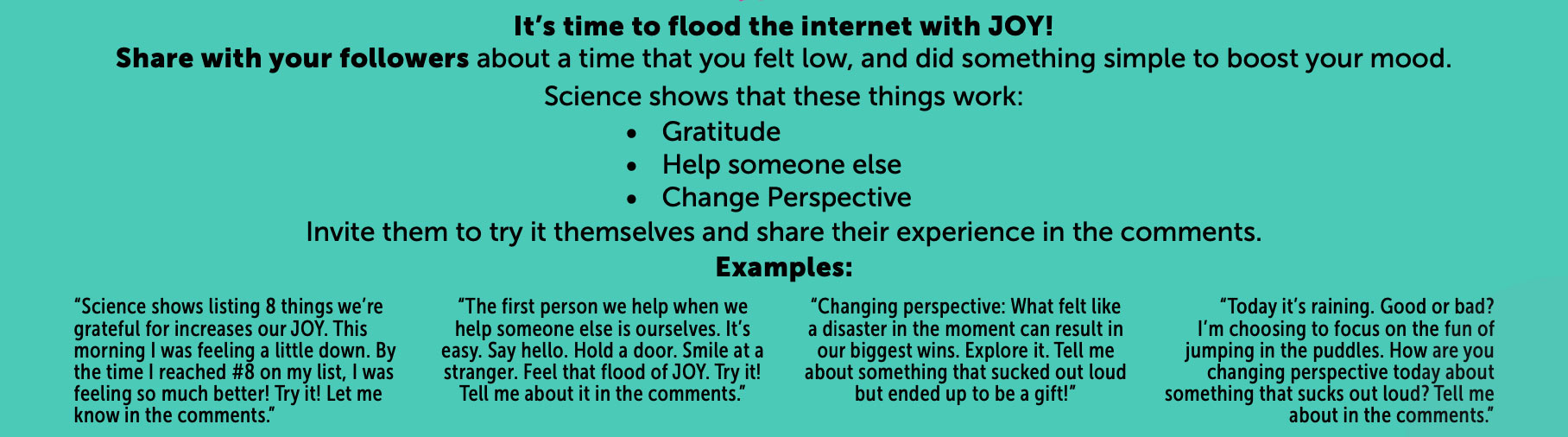

Through our work with HelpGood, more than 1 million people, 783,000 via social media and 220,000 via email, joined the JOY community from around the world. They receive updates about more JOY opportunities and get inspired by the wisdom of His Holiness and Arch, and each other.

The “Courageous” Impact Campaign

In some ways, since distribution was not going at all how we hoped—or how experts expected it would go—we started looking at the impact campaign as our DIY distribution plan. We thought of this in two ways. One was, of course, getting the film watched. But it was even more important—because of the mandate by our two men—to get the ideas of the film disseminated and incorporated into people’s lives. We started becoming less attached to the stats about how many people watched the movie, and more invested in what happened after they watched the movie, and/or read something on our social media, and/or tried out an Act of JOY in their own lives, IRL.

A silver lining of the pandemic:

You know how documentaries are famous for going over budget? Because of the pandemic, we actually saved a lot of money. By the time the pandemic hit, I had already directed the shooting in Dharamsala with Arch and the Dalai Lama and we had 18 hours of footage from that alone. But there were interviews with other people that we were planning to get. We had planned on being on the road for 68 or 69 days shooting all these other things in South Africa, and again in India, and with scientists in different places.

All that on-location shooting was cancelled. Everything kept getting shut down, but thank goodness we could get those major interviews we needed remotely. We could have crews there, see what they were seeing, and Louie could talk to the remote crews on the ground there. I felt for him. I got to spend all that time with the holy men, and by the time he started, the pandemic prevented him from traveling. But we got the footage we needed—and we saved a bunch of money from nixing all that travel and by using more archival footage than we had intended.

At the time it felt like a swift kick to the gut. We had planned all that on-location filming for a reason. And we didn’t have a rough cut of the film yet, so we didn’t know for sure how it was going to hang together. But by being forced to make a film a different way, we ended up saving about $250K. Since this initiative had been impact-first from the beginning, that money wasn’t going into anyone’s pocket. It would go directly to the impact campaign. The original plan had been that a major distribution partner would buy the film and we would use that money for the impact campaign—but it turned out that we hadn’t needed to rely on one of those distributors for that money anyway. With the extra $250k, we had many more interesting choices before us for the impact campaign.

Incorporating the film’s messages into people’s lives

What mattered most to us was that the messages of the film make it into people’s brains and into their lives. They didn’t have a preference necessarily whether that happened through a book, or a movie, or something else entirely. Since we had little control at that time regarding what was going to happen with the film beyond the “safe” things we were doing, we set our sights on helping people incorporate the JOY lessons in their day to day.

I have always been especially drawn to what the Holy Men have said because they use science. His Holiness works with scientists and appreciates studies that shed light on the wisdom that spiritual traditions have been teaching for millennia. The intersection of spiritual wisdom and science is compelling to me. On days when life just kind of sucks out loud and I’m having a tough time, I remember that if I help someone else, the first person I help is myself. It’s science and common sense. Even if it’s a teeny thing, like opening the door, smiling, etc., I make sure I do that and I immediately feel that burst. And the thing is, it’s just not me. It’s science. Science has shown that that’s just the way our bodies are wired.

We were talking to one of the great activists on the planet, Jamie Drummond, who co-founded ONE with Bono. He was one of our advisors. We told him my idea of having high profile people share on social media how completing what we call Acts of JOY will make anyone feel better. So, we would ask The Rock, for example, to go on social media and remind folks that helping others can increase your joy, and to challenge his followers to go try it out and report back in the comments. The idea was that it would get spread more virally and we would get numbers back that show that it happened. We could count how many people did something.

Jolene and I were explaining this to Jamie when he said, “Well, Peggy, why don’t you do a citizen science project with it?” And I’m thinking… “Citizen…science… Is that the thing where English people count birds and butterflies in the spring?” And he said, “It’s also the Human Genome project, Peggy.”

Right. Then I understood the potential here. I immediately wrote to a friend of mine, Elissa Epel, a great scientist at UCSF, and asked, “Do you think we could do a citizen science project on Joy with people doing Acts of JOY?” The next day she wrote back with the outline of a plan and said, “Yes, we could. And Berkeley’s on board and so is Harvard.”

The BIG JOY Project

Together with research scientists from these institutions, we selected seven science-backed easy, tiny actions that are shown to boost mood, that can be done anytime, anywhere, by anyone, for free. Then we named it “The BIG JOY Project.” If you go to bigjoy dot com, you’ll find a fast-food Bolivian chicken wing site, which, I’m sure brings a lot of people joy, but that’s not it! Our site is hosted on the Greater Good in Action (GGIA) page on UC Berkeley’s website, https://ggia.berkeley.edu/bigjoy.

People can sign up from anywhere in the world and try one Act of JOY a day for seven days and rate their mood before and after, and again before bedtime. At the end of the seven days, they get a personalized JOY Report that shows which Act of JOY had the most positive effect on them, and to what extent they enhance their level of joy. Participants report that they after the seven days, they feel on average 25.9% more joy and well-being. Also, that the quality of their sleep improved. And it's all free!

We teamed with top researchers in neuroscience and psychology to create the largest joy-focused citizen science project. Joy Partnerships included The Network for Emotional Well-being: Science, Practice, and Measurement, a collaborative project between UCSF, UC Berkeley and the Harvard University’s T. H. Chan School of Public Health. We also partnered with the Center for Healthy Minds at University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Positive Activities & Well-Being Lab (PAWLAB) at UC Riverside.

Now 100,000+ people from 213 countries and territories have participated, completing more than 420,000 Acts of JOY! It is the world’s largest ever citizen science project on joy. In addition to the participants benefitting, it has also created an extraordinarily large dataset that research scientists can use to unlock the next frontier of our understanding about how we can all experience more joy. The first peer-reviewed journal articles based on this data are about to be published. We didn’t set out from the start to advance the field of science regarding joy and happiness, but it was a welcome addition to the overall impact that made both Arch and the Dalai Lama smile.

Participants also had 23% increase in ability to have positive emotions!

It made us smile as well. We always knew we wanted for our impact campaign to go beyond simply maximizing the number of people who watched the film, and while advocacy campaigns to contact elected officials make sense for some documentaries, it didn’t for this one. So, finding a simple, doable action step that helps the individual while also helping the collective was a particularly big win to us.

Making the Film Available for Free in the Global South… our UNITE for JOY Event

While our pitch team kept getting nos from the major distributors, we were getting desperate to share the film, especially in the Global South, where the pandemic was causing skyrocketing mental health needs, and where there were the fewest resources available. We had already witnessed, through the film festivals and community screenings were happening, that when people see the film, they feel better and they learn reframes that help them with the challenges in their lives. We needed the film to be available ASAP, and for free, especially in the Global South.

We partnered again with The Film Collaborative, who had recently received a small grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to do a “Global VOD” initiative. We were shopping the film around to platforms around the world and offering the film to them for free—zero license fee—simply asking for it to be put on their AVOD (or even SVOD) platforms. Finally, we were in talks with a huge platform in Africa that wanted the film.

In the meantime, one of the creative paths we were considering was partnering with Facebook. Individually, each of us had questions about whether Facebook was values-aligned, but at the same time, the Dalai Lama and Arch both had their own active Facebook pages with active followings. It seemed reasonable to go to people where they are already hanging out. And as we discovered, especially in the Global South, Facebook was king. Although certain new social media outlets were considered trendy at the time by young people in the U.S. or Europe, and therefore prioritized in those regions, those apps were actually only a drop in the bucket compared to the sheer billions of people who use Facebook worldwide. Even when targeting young people, the number of young people on Facebook far surpasses that of any other platform.

I had found out, though, that Facebook has a special program for when people they call “Public Figures” work together through the platform on a mission that Facebook supports. In our case, Facebook offered to connect the Facebook pages of any Public Figures we got to help promote the film if we were willing to do a simultaneous free screening of the film through all of their actual pages. Facebook also offered gratis ad credits to amplify the screening and the comments that were posted about the film and the screening event.

If we had already had a major distribution deal, I’m sure this would have been a nonstarter. Even though we of course would have maintained our standard carve-outs for free community screenings at places like faith communities and schools, a global free screening at this scale probably would not have been described as simply “community.”

Armed with this opportunity—and no other at the time! We scrambled to reach as many values-aligned Public Figures as possible who had large Facebook followings. The more people the Public Figures reached, the more people we would reach with this film. This strategy had the added benefit of their followers finding out about this film from them. That way, people would be more likely to give the movie a try even if they typically didn’t watch documentaries. This was especially important with younger audiences for whom the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Tutu were not known well, or at all.

We called the global watch party UNITE for JOY. It happened June 2, 2022, and we treated it as our global premiere. We were blown away when the event got 13.3 million views of the film and 138 million impressions, with participants spread out around the planet. Compared to the limited reach that even the major streaming services have in the Global South, this was a major win. We had finally gotten our global reach, where people could watch the film for free!

It was a major success regarding our impact-first distribution, but it did come with a cost. As soon as the platform in Africa heard about the free Facebook global watch party, they cancelled their deal with us. Even at the time, we knew we had made the right decision in charging ahead with getting the film to as many people as possible as soon as possible.

Our social media campaign, plus the global watch party earned us a few awards.

Global JOY Summit

During this time in “distribution desert,” we were all-in on the global free screenings, so we partnered with Mind & Life Institute to create what we called The Global Joy Summit, a free four-day online event that took place November 13-16, 2022. It featured 30+ spiritual teachers, JOY researchers, social justice activists, and artists to help participants enrich their learning about creating JOY. We got almost 200K participants watching in 29 countries. It also offered a free screening of the film. 120,000 people watched.

The First Major Distribution Deal and What Happened with Sales

Let’s rewind for a second. I mentioned earlier that Orly Ravid of The Film Collaborative and WME were trying to secure a distribution deal and that that was not happening at first.

The first really huge “yes” we got for distribution was the BBC. This was especially meaningful because during the Dalai Lama’s most difficult years, the BBC was his lifeline for real information about what was going on regarding Tibet. Definitely a full-circle moment that brought tears to all of us, and I’m not even a cryer. In addition to knowing it was so poignant for His Holiness, it had been a long few years. I know my fellow documentary filmmakers know what I’m talking about. It can feel sisyphian at times. The BBC deal was a watershed moment. And the CBC came on too.

In the end, the JOY Team arranged for the film to be available via the above broadcasters and streamers. Currently, the film is available in 244 countries and territories around the world, including on the Netflix platform in all of Africa, Latin America, the U.S., the UK, Australia, and New Zealand.

We understood that a certain percentage of the world's population will only watch a movie if it's presented via these platforms, due to their viewing habits of how they learn about and watch films. These platforms also provided for additional marketing and publicity of the film, and, in the case of broadcasters like the BBC and CBC, is free to watch.

But the story of how this all happened was not a neat and tidy one.

It was a tricky dance, for sure, because when typical distribution deals were not happening, the JOY Team forged ahead with huge free screenings such as the global launch on Facebook. This allowed us to have some interesting conversations with potential distribution partners who are used to full exclusivity of films they accept. Such as the Netflix deal. They came back around. It’s not like we didn’t pitch them initially. But we did such amazing work with the impact campaign and the rest of it that it became possible. I can’t discuss who on our team made it happen, but it was well after the initial sales pitching was done. We are so grateful for their non-stop efforts. Had we said yes to the African platform, we would never had gotten to yes with Netflix.

The Big Picture

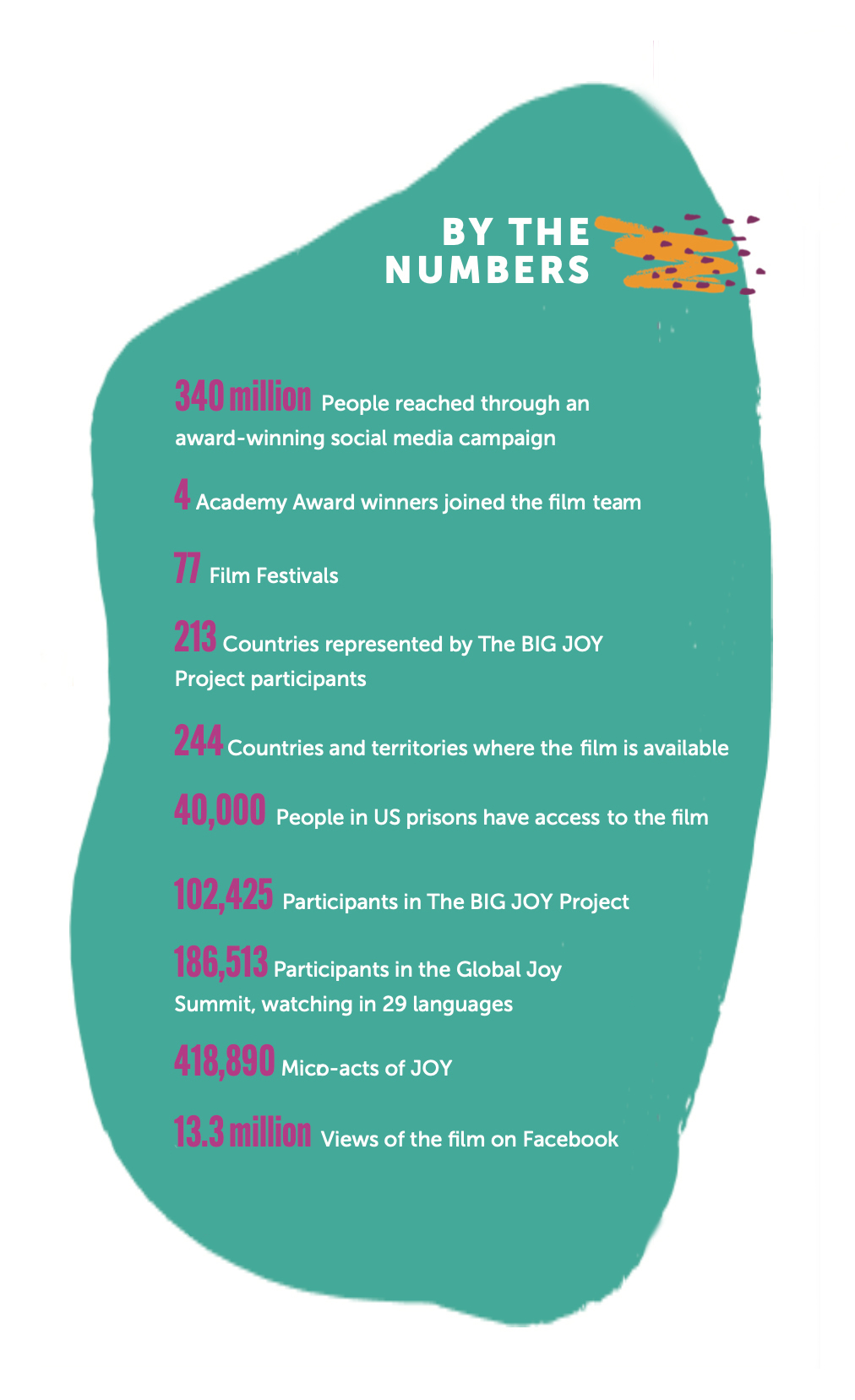

All the accomplishments that I’ve outlined above, and the stats in the “By the Numbers”—when you just list them like this, it seems like it was a cakewalk. But, in reality, the highlights of the impact campaign—working with Facebook to do a global event around the film and working with Berkeley etc. on Big Joy—sort of mark all the times we got the s&%t kicked out of us. We had plans. The universe didn’t particularly agree. And that’s when it started to get interesting.

We explored every Sales alternative imaginable way to get it out there. We stuck with it. During my interview session with David Averbach of The Film Collaborative for this case study, he marveled at what he generously called my tenacity. He wondered whether most filmmakers would perhaps have given up, either out of exhaustion or out of a more immediate need, like a financial one, to move on.

I would say this, though. In all my journalism and in all of my television projects, it was always about social justice. It was always about the bigger pictures, always about, “How do we make this world better in whatever way we can?” It’s not someone else’s job; it’s our job. So, I come at it from an activist point of view, and I left full-time television and went all activism by co-founding two international anti-slavery organizations. I can’t quit that ever…it’s not going way fast enough! And I think that a project such as this calls for an unreasonable love.

Having said that, however, I think many documentary producers must do the same. I don’t think I’m so different in this respect. As an activist would, I have a job, I want to help create change through this vehicle, through these astonishingly wise men to a desperate world. And I do believe that requires an unreasonable love. You know, the kind of love that you want this to happen so much, and you’re so committed to it, that that love will pick you up off the ground when you would much rather stay down there and just rest a bit. It never would occur to me to make a film and not doing every possible thing you can to get people to see…that is absurd! You just wasted all your time. I don’t have that much time…I’m freaking old! I want to make use of every moment. And...this project attracted so many great people with big hearts and huge talent. We were all determined to get the Holy Men’s message to the world.

Every single thing was hard. Every single thing kicked all of our asses. When David said, “There’s something about you such that you succeeded where others would have given up,” all I can say is that it’s not like I didn’t pay a huge price. I lost my hair. My face got frozen. I developed Bell’s Palsy when I was in Telluride, I had to go to that festival with my face frozen and speak like that in front of a huge crowd. It wasn’t pretty.

But you cannot be entrusted to tell the story of some of the wisest men in the world and spread their story, and then you go, “Oh shoot, it’s not working.” You have to be as “all in” as they are. And really believe in their message, because every single day we were getting all these comments from people, “This has changed my life,” “I will always remember this.”

So, I always thought that the impact campaign was as important as the film. If you don’t do that, I mean, what’s gonna happen? No one’s going to see your film. And, if you want to create change, that’s what it takes. That’s the ultimate payoff.

You can deliver the harshest messages in the world, but if you can get somebody to laugh, they laugh. It opens up their spirit and the message starts finding its way. And the world needed it and still does.

Once you commit to any project, it can be as life-affirming as it is ass-kicking. I know myself. I know that once I decide to do something, that’s when that unreasonable love steps in, I have got to do it. And I don’t take it on if I’m not willing to do that.

But David made one other point, and that was that if you are a documentary filmmaker, and that’s the hat that you’ve been wearing for several projects, it can be kind of limiting. Because you always have to filter it through, “what’s my next film?” But since I don’t have the kind of background, perhaps I’m much freer to look at the content and say, “what’s important here?” Maybe that’s a luxury that other people don’t have. It certainly allowed me to surround myself with people who were really great at what they do, and they didn’t have to come from the documentary film world. Some of them did, but they were all great. That’s number one. And I don’t think most things deserve a documentary, but if they do, you have to be willing to go the distance. My grown-up job is fighting slavery. It’s really hard sometimes – and imagine how life destroying it is for the people enslaved. So, it’s true the film was difficult at times but much easier than fighting slavery where lives are at stake.

Maybe it is because the issue of slavery can be so depressing that I’ve always been conscious about the need to bring joy to the work whenever possible. I think of joy as the ultimate clean energy that fuels long-term change. If our activism is powered by anger, that doesn’t burn clean. We might get a lot done in the short term, but we’ll burn out and probably feel miserable along the way—which is not pleasant to be around. If we fuel ourselves with joy instead, we can keep going and going and have a good time with great people.

TL;DR

The documentary film Mission: Joy—Finding Happiness in Troubled Times, released on the heels of a related international best-selling book, was heralded as “an antidote to the times” and featured two of the most well-known and respected individuals in the world, the Dalai Lama and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Filmmaker and human rights activist Peggy Callahan, serving as co-director and producer on the film, had been entrusted to deliver the message of these two holy men to carry their message of joy to a hurting world. It was bad enough that her filming plans were severely altered by the pandemic. But after the world premiere of the film at Tribeca in 2021, she received no acquisition offers, even after top agents in the film world, expecting a bidding war, told Callahan to keep her cell phone on 24/7 (self-censorship in the industry around being involved in a project that had to do with the Dalai Lama—a third rail for doing business China… they were weighing this against the billions of dollars in revenue that could potentially be at stake if the Chinese government viewed their buying the film as promoting the Dalai Lama—someone they see as their enemy). She picked herself up and got to work. She and her team burrowed underneath and eventually through the existing film distribution system to have the film accomplish the following:

- Reached 13.3 million people through a global watch party

- Debuted at #2 on iTunes for documentaries

- Secured distribution on Netflix and nearly all major streamers

- Reached 340 million people through an award-winning social media campaign

Yes, they had some pitfalls, but on each occasion, they pressed on, turning lemons into lemonade. To meet the holy men’s requirements that the film’s distribution be centered around the Global South, not merely the Global North, they made an early decision to raise funds only from nonprofit, not for-profit, sources. This allowed them to retain full control, which eventually paid off. When the pandemic hit and needed to forgo travel, they were able to save money, and those saved funds were then put into their impact campaign. In fact, they developed an Impact-First Revenue Model that prefaced the impact of their mission over the distribution of their documentary. Lastly, their two-day global watch party ended up scaring off a huge platform in Africa, but in the end they got something even better: after their award-winning social media campaign, Netflix reconsidered and acquired the film in many territories, including Africa.

They also created the largest joy-focused citizen science project in history. Have a look at these results from participants before and after Big JOY:

- 25.59% increase in peace of mind, well-being

- 12% improvement in sleep

- 23% increase in ability to have positive emotions

- 27% increase in feeling agency over joy in their lives

- 30% more content with friendships & relationships

- 34% increase in feeling in control, coping well

Need some more JOY in your life: Take the BIG JOY Challenge here, for free.