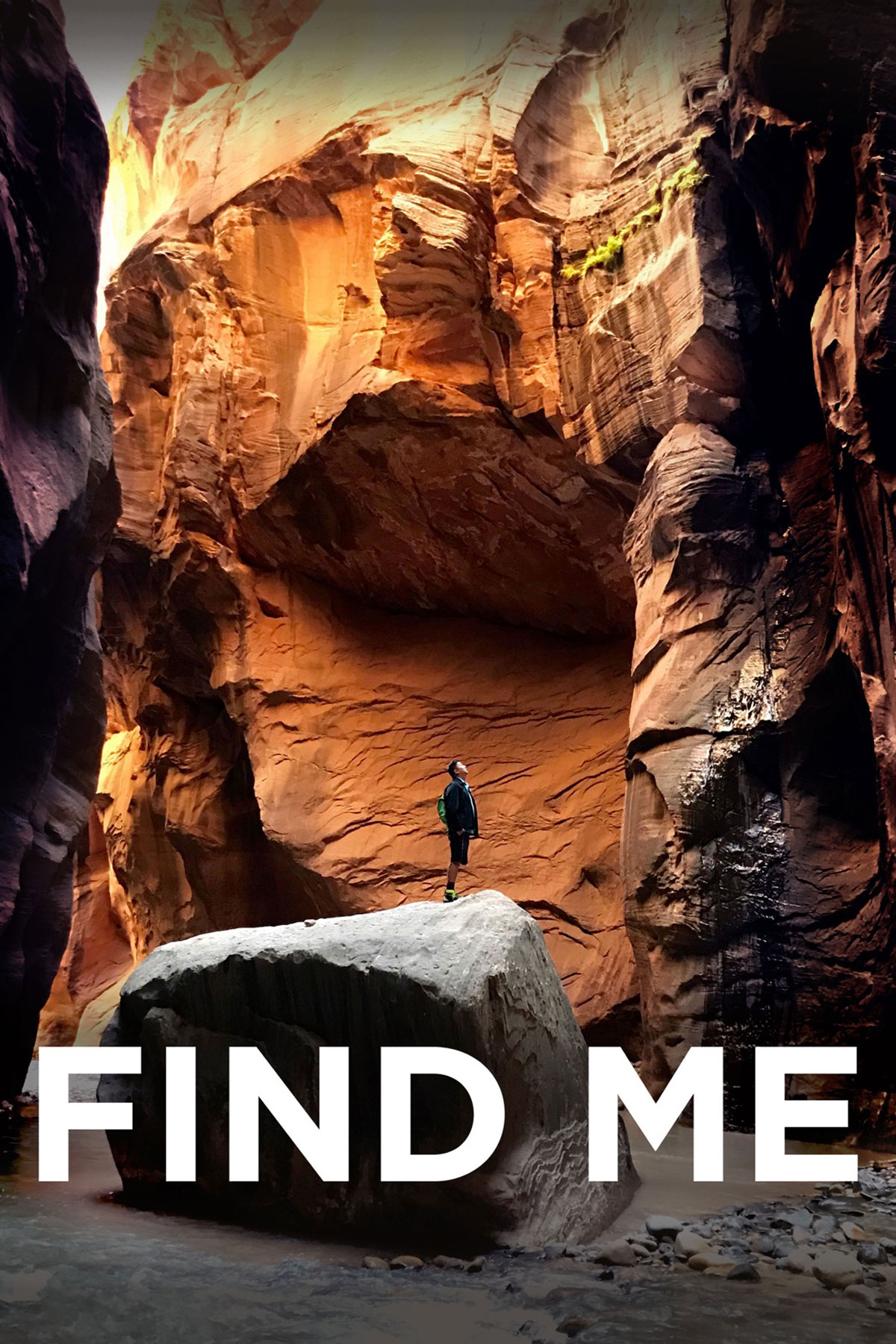

How Find Me Found Its (Outdoorsy) Audience Online

April 22, 2020

Find Me is a narrative feature about an emotionally wounded accountant, who breaks away from his routine to find a missing friend. That friend has left clues about her whereabouts in National Parks across the Western United States. Tom Huang, who wrote, directed, and edited the film, also plays the lead. This was a smaller project that Tom decided to do in order to keep busy, as many filmmakers do, while waiting for a feature project with a larger budget to come through:

Tom Huang: The larger indie project was taking forever to get off the ground and I was itching to just shoot something. So, I started thinking of ideas. During that time, I happened to be hiking an amazing hike in Zion National Park in Utah called the Narrows, where you are hiking in the Virgin River as it cuts through spectacular, narrow slot canyons with rock walls that reach to the sky. As I’m experiencing this, I stared up at these amazing canyon walls and thought to myself, “you know, I need to make a film where people point to the movie screen and say, ‘I need to go there.’” I felt like this kind of very accessible, magical experience is something everyone should do. So that day, I started writing the outline for the script for Find Me.

His secondary goal was to make a film that centered around how friendship and nature can heal and inspire. The 103-minute film was shot over a year, in periods of 3-4 days a month, with scenes edited right after each shoot.

This was Tom’s second micro-budget feature, with an overall budget in the very low six figures. Find Me got some great traction at festivals, booked a one-week theatrical at Laemmle Music Hall in Beverly Hills, received positive reviews in publications such as the Los Angeles Times and The Hollywood Reporter, held a handful of hybrid-theatrical event screenings, devoted more than $10K to social media ads, worked with organizations like the National Parks Conservation Association and Southern California REI stores to build brand awareness, and worked with distributor Indie Rights on a creative distribution plan that included VOD and DVD/Blu-Ray. Indie Rights retained Ships and Airlines rights, but Educational and Broadcast TV are still available at the time of this printing. Find Me is currently on track to make its money back very soon.

Festival Premiere

Find Me did not get into Sundance or SXSW, although in the case of the latter, it made it past the first round. It was not getting any traction even from festivals where Tom had screened his previous works. Feeling frustrated, Tom wondered whether it was even possible to predict who would respond positively to the film, so he decided to leave it up to fate and went with the first festival that accepted it. That festival ended up being the Chicago Asian-American Showcase Film Festival in the Gene Siskel Film Center, and he premiered in April of 2018.

Tom had a rewarding experience premiering the film in Chicago, in a state-of-the-art cinema with engaged audiences, who shed tears and stayed after for a great Q&A. An unexpected perk of this particular festival was that he could leverage the Film Center’s PR department and contact reviewers. Normally, Tom would have had to write to every publication within 50 miles by email and beg for some sort of coverage, but this access eliminated that leg work. Two positive reviews came from Rotten Tomatoes approved critics, which helped the film achieve a 100% Rotten Tomatoes critics’ rating.

Tom didn’t really invest in marketing, publicity, or social media during the festival run. He talked up the film on social channels, of course, but wanted to hold out on paid social advertising until the distribution phase. His main takeaway was two positive reviews in major midwestern publications.

As the festival run went on, Tom noticed that his film was consistently knocking out audiences in ways he never thought he’d see, drawing full houses and moving viewers to tears. People kept saying that they “came to see the National Parks but ended up getting caught up in the story.” This is when he realized he had a film that connected deeply with audiences.

The Search for a Distributor

For Tom’s second feature film, Why Am I Doing This?, which was also a micro-budget film, he also had some festival success, winning a handful of Best Feature film awards with positive reviews. For that film, he had gotten a sales agent who made a distribution deal with a distributor that ultimately ran off to Canada with all of the film’s revenue. Tom eventually got his rights back, and with the help of an aggregator put the film back up on digital platforms himself, but unfortunately by that time the film was too old to garner any meaningful earnings.

When it came to finding a distributor for Find Me, Tom discussed the project with potential sales agents, but the ones he talked to actually wanted upfront money. Tom sought advice from fellow filmmakers, who told him that he’d be crazy to pay anyone to look for a distributor for a film of this size. He expressed how he was feeling at the time:

To be honest, after a nightmare distribution situation that happened with my last film, I didn’t have much hope about distribution, knowing that I’d be making another microbudget film with no big stars. But I knew that I wanted do things differently with this film, namely, not rely on people like sales agents, and be much more stringent in what I wanted from a distributor. I knew that I could always self-distribute if I needed to and still get positive results.

So, Tom began looking on his own. He knew his audience was out there—people interested in the outdoors and National Parks—and if someone were to distribute the film, they’d have to prove that they understood how to market it to these folks.

As he talked with a handful of distributors, he found that every offer wanted to take 40-50%, with no MG, plus other ‘marketing’ and miscellaneous charges, to distribute to platforms that Tom could put the film on himself. They also seemed to have absolutely no specific marketing plan. From his research and experience (and basic common sense), he knew that nobody would watch the film if they didn’t know about it. So, if these distributors wanted to take half of the film’s take without being willing to do any real marketing for it, what good were they for a film like his?

After doing lots of research and talking with other filmmakers, he realized that there were distributors that catered to small films like Find Me. He discovered Indie Rights, who take 20% with no upfront costs to put the film on every key legitimate digital platform out there. He wouldn’t have to kill himself doing all the distribution legwork for the project and decided that paying someone with experience to take care of all of that was well worth that kind of cut.

After vetting the distributor, talking to multiple filmmakers who worked with them and exploring more what they were about by listening to podcasts and reading articles by Linda Nelson, the head of the company, Tom found that they were transparent with their bookkeeping, accessible when they were contacted by a filmmaker, and on-time with their payments and reporting. They also had vast experience dealing with the major digital platforms. The simplicity and transparency of how they worked really appealed to him. And all of this at no extra cost to the filmmaker, and no hidden charges after the fact—as long as the filmmaker delivers the film with the proper specs for digital distribution, there are no upfront costs for distribution on Indie Rights.

Although Indie Rights doesn’t do paid marketing (which was fine by Tom given the percentage they were taking), he appreciated that they did spend time posting and promoting their films on their social media accounts, as well as spreading their filmmakers’ social media postings.

Tom decided to license Digital and Home Entertainment worldwide rights to Indie Rights. One of their stated selling points was that they do international sales for their films: they have a booth at Cannes and at AFM and promote their films on the two biggest buyer databases, Cinando and The Film Catalog. They also noted that they are considered a “studio” by Amazon, and therefore have access to more than twice the number of territories that filmmakers who go direct with Amazon Video Direct can avail themselves of.

This choice let him put all of his distribution money into theatrical and marketing, thereby minimizing costs as much as possible. Tom did his own one-week limited Los Angeles theatrical while releasing simultaneously to digital formats via Indie Rights.

Theatrical / Hybrid Theatrical

The filmmakers did their own limited Los Angeles theatrical release at the Laemmle Music Hall theater in Beverly Hills the Friday after the Memorial Day weekend in late May 2019. They booked a shared screen with another indie feature, so Find Me played twice a day in a week-long release (i.e., this was not a four-wall, meaning that they didn’t have to pay to rent out the theater, but they did have to split the box office with the theater). They spent around $800 on Facebook ads targeted towards people that lived in Los Angeles and that were interested in the outdoors (which also doubled as advertising that the film was available on Amazon at the same time). They got positive reviews and write-ups in a handful of publications, including the Los Angeles Times and The Hollywood Reporter. These helped Tom reach the Rotten Tomatoes critical mass of 6 reviewers for RT-approved critics, which allowed it to have an official RT score of 100%. Being that the filmmakers are L.A. locals, and by tying in some promotion at the SoCal REI stores, the film brought in about $2,500 for the run, which, as it turned out, was the top-grossing screening room for that theater that week. The filmmakers felt the theatrical release was worth it for the marketing value, as well as just being able to screen the film on a big screen for their friends and supporters in Los Angeles.

Tom also did single event screenings in four other cities, which brought in another $1,500 in screening fees / sponsor revenue. Tom reinvested that back into marketing the film, but it turned out putting on event screenings was quite a lot of work for a relatively small amount of money. Post theatrical run, there was still strong interest to put on event screenings across the U.S., but it ended up being more work than Tom cared to deal with, so he wound that down and focused on digital, which was happening simultaneously.

Digital Release

The digital component of the quasi- “day-and-date” release saw a launch on Amazon TVOD in the U.S. (rentals/purchases), as per Indie Rights’ usual strategy.

Even before signing on with Indie Rights, Tom was well aware at the time of their release that it was possible for filmmakers to go direct with Amazon. But Indie Rights had also explained to Tom and his team that because of their longtime “studio” relationship with Amazon and the fact that they had a large number of titles with the platform, Indie Rights had a kind of privileged relationship with Amazon. (In fact, on the Indie Right’s website, it states that their relationship with Amazon dates back to the days of Amazon UnBox, which was the predecessor of Amazon Video, and that the first feature that Indie Rights released digitally was used by Amazon to promote itself as a platform for five years). They also made the argument that limiting the release to one platform gave the film the best chance to generate enough traffic to boost the film’s success on Amazon in such a way that it could leverage Amazon’s algorithm so that it would start automatically suggesting the film to other users. Such a strategy made logical sense to Tom.

We ended up having a great start on Amazon TVOD…I’ve been told by a lot of my filmmaker friends that it’s been tougher to get revenue from TVOD, so we were very happy with our results. Some general numbers to give you an idea of what we were getting: in our first month of TVOD release (the remainder of Q2 2019), the film brought in $28,075 gross (before Indie Rights’ cut), which represents half of the rental/retail price paid by viewers (Amazon’s usual split is 50%, and this was the case with Indie Right’s deal with them as well.)

Indie Rights maintained the strategy of keeping the film exclusively on Amazon TVOD for another five weeks. On July 9, they launched on GooglePlay TVOD, which is probably the first time the film appeared in Canada. (They didn’t have the film launch on iTunes until November 2019.) On July 16, six weeks after their Amazon TVOD launch, they made the film available for Amazon Prime SVOD in the 150+ territories.

When we released on Prime, it started out steady but slow…then, all of the sudden, the viewership exploded, and suddenly there were a whole lot of people watching the film, which prompted Amazon to suggest to more people, as well as put our film on suggested Top Film lists for Dramedy, Comedy, Adventure and Popular films. We stayed on that list for a good 3-4 months straight, and almost daily we’d be getting emails or posts from people saying how the film inspired them, as well as texts from all sorts of friends/family who heard from someone that saw the film and suggested it to them.

Over the next three months (Q3 2019), the film grossed $46,543. This includes some revenue from TVOD and TubiTV, but most of it was Amazon Prime.

Indie Rights is still working to get the film on other platforms and markets. They extended AVOD to Roku as well as Indie Rights’ own streaming services. The revenue from AVOD has been small and slow to start out, but it’s been very slowly increasing bit by bit. TFC has heard that many films do very well on TubiTV, but that they are taking more new and new-ish releases, and not as many library titles these days.

DVD/Blu-Ray and Other Rights

To avoid steep upfront costs on DVD/Blu-ray, Indie Rights works with a company called Allied Vaughn that creates and sends discs on demand, to minimize overhead cost ordering DVD/BluRay stock. The filmmaker still retains educational, broadcast TV, and Ships and Airlines rights available at time of printing, and the filmmakers are still waiting to hear numbers on DVD sales.

Marketing Push: Social Media Ads, Press Reviews, and Partnerships

Most of the marketing budget for the digital (and theatrical) release went to targeted social media ads, primarily Facebook ads, where the filmmakers could test and target specific audiences. Tom created a special trailer for the Facebook ads and tested different lengths. He discovered that, for Find Me, a 90-second version of the trailer was actually the one that more people engaged with, which is not the norm, as conventional wisdom is to stay under 30 seconds for Facebook ads. These ads got huge traction, with people treating them like posts, tagging their friends and commenting that they wanted to watch the film.

Find Me already had some great film reviews from the festival run, but it later received more positive reviews from key publications that were important to the film’s core audience, such as Outside Magazine, which dubbed it “the Indie Adventure Film we all need.” The film also got a great write up from SIERRA, the Sierra Club’s national magazine. Reviews came out as a slow drip, rather than all at once, which built a constant flow of awareness.

Additionally, Tom partnered with the National Parks Conservation Association and they did social media posts to their 1M+ followers, highlighting specific hikes from the movie. Another partnership was with the REIstores in Southern California, where Tom was an unpaid guest speaker to in-store audiences at special workshops, discussing the hikes and the film, which also helped build audience awareness.

The team worked with two PR firms, one focusing on indie film PR (David Magdael & Associates), and also What’s Up PR, a firm specializing in outdoor products. What’s Up helped them get a presence and screenings at the Outdoor Retailer Summer Market during the summer, as well as reviews and features in outdoor publications/blogs. Tom also reached out to outdoor bloggers/influencers, convincing several of them to tell their followers about the film.

I can’t stress enough that though distribution is of course important, for us, it was our work in marketing the film that I believe helped spur its overall success and I would urge indie filmmakers to consider that when they’re ready to release their films. Simply put, your film cannot exist in a vacuum.

Most people are aware that with when you make your film available non-exclusively on Amazon SVOD, unlike exclusive SVOD deals such as through Amazon Studios, or even via their now-defunct Film Festival Stars program, there is no upfront payment or MG. Revenue is paid per hour viewed, and while the rev share used to be higher (15¢ for U.S., higher for some distributors and aggregators, and double that if one was a part of the Film Festival Stars Program), as of April 2019, the baseline rev share lowered to 6¢/hour. That rate can be a few cents more depending on something called Customer Engagement Rating (CER), which is determined by things like how much people share the title, put up a review, or even buy things after watching the film. The CER measures your ad’s expected engagement rate compared to ads competing for the same audience.

I don’t think filmmakers realize how nebulous and difficult it is for those of us with small films to bring up our CER scores—because how big a star your actors are, and your (theatrical) box office numbers, also contribute to the ranking. This means that even if you bring in what you think is a lot of eyeballs, your ranking may not even change. More on how Amazon’s CER works can be found here.

Even though the rev share doesn’t sound like a lot, Tom and his team believe that the film’s overall success had a lot to do with their success on Amazon Prime, which the filmmakers in turn chalk up to a mix of social media ads, great media coverage from key publications and Amazon’s suggestion machine, along with the various forms of marketing/partnering to get the film to a point where word-of-mouth could blossom at the numbers needed to make a financial impact. Tom edited all of the trailers himself, and created the digital ads, which was time-consuming, but it meant they didn’t have to pay an external vendor to do it. (Tom is lucky that one of his side freelance jobs has been as a TV/Film Promos producer and editor, so he was uniquely confident that he could do those things himself for his film. He wanted to remind filmmakers who may be reading this, that do not have this kind of experience, to consider working with someone with a background in promos/trailers to help write and create a good trailer.)

Tom heard that he should spend a minimum of $30K for social media ads but, not having that much to work with, started by spending $10K and waiting to see the effects. As the film did better and better on Amazon, starting with TVOD and moving into SVOD, Tom felt more confident in putting a little more money into social media ads, moving money from other parts of the marketing budget. All together, they did not end up spending even close to $30K on social media ads, but the amount they did spend was spread out over about 5 months, with most of the spending done during the first 3 months of release.

Tom appreciated the 50-page filmmaker guide for how to maximize your SEO—website, Facebook page links, certain number of posts—that Indie Rights provides all their filmmakers.

About 60% of our efforts were based on the research we did and what we already knew, and about 40% were based on that guide. There were definitely a lot of little things in there that we thought were very helpful and specific—for example, what you should have in your Facebook banner photo, what kind of video categories should be on your YouTube page, etc. It was really good to have this sort of checklist of essential things to do for marketing and social media set-up.

The thing about going through a distributor is that you do not have direct access to the metrics of how your film is doing. Some aggregators are the same way, but Quiver, for example, has filmmaker portal that hooked up to iTunes Connect, and one can see estimates as soon as they are reported, which most of the time is the next day. But Quiver does not (yet) provide those kinds of numbers for Amazon. However, if one goes direct with Amazon via Amazon Video Direct, one can see daily estimates. So, we asked Tom how he knew that his ads were working. He responded as follows:

Well, first we would look at the response from the actual ad, like comments, likes, etc. I don’t have anything to really compare it to, but seeing the kind of comments and that people are liking it and tagging people in comments to share it with—I think that was a good sign.

We would also look at numbers provided by the Facebook ad portal itself.

Looking at those numbers (what is pictured in the image above is just one of quite a few statistics they give you), which sometimes required the help of some friends who were digital ads consultants, I began to understand what the numbers meant and how to figure out whether things were going well.

Lastly, to know the actual minutes viewed that Indie Rights has access to… they don’t automatically give those numbers to you with your reports, or even periodically, as they have hundreds of films, but Linda is accessible enough that if you ask her from time to time when they’re not swamped with AFM/Cannes or making quarterly payouts, they’ll give you minutes viewed numbers during a requested time period (a few weeks or a month). This is part of what has made it a positive experience working with them, though I’m not sure how they’d be able to respond to those requests if every film asked for them at the same time.

Even though Tom’s measurement of “high engagement” wasn’t exactly the same as knowing his exact daily CER, he was able to glean enough information to know when things were looking good, and when they started to shift.

Tom noted that one’s CER is easier to maintain when your film is doing well, but harder if your film is not. After five months of streaming, Tom pulled back on his marketing budget and the amount of attention he spent on promoting the film online, which had an effect on viewership and the CER rating. When your CER drops, the amount you get paid per view is also affected.

At one point, Indie Rights gave Tom and his team feedback on how to get the CER rating back up, but after putting all of this marketing work in, the filmmaker felt the need to move on and make movies again. Tom wants to remind any other filmmakers who might be reading this to remember this if you choose to market your own film:

You can definitely do it, but it’s not sustainable for you in the long run if you want to keep making movies and if you care about your general well-being.

And even though viewership has started to drop (Q4 2019 gross was $19,399.97), there are still manypeople watching the film, and Tom believes it now has taken on enough of a life of its own to keep that up to a certain extent.

Analysis and Takeaways by the Filmmaker

As stated earlier, if everything goes as planned, the film should be into the black sometime very soon.

|

Digital Earnings |

Gross |

Net |

|

Q2 2019 (June only) |

US $28,075.92 |

US $22,460.74 |

|

Q3 2019 |

US $ 46,543.34 |

US $37,234.67 |

|

Q4 2019 (estimated) |

US $19,399.97 |

US $15,519.98 |

Tom knows that getting money back for a small microbudget film is kind of a long game, but he believes his start has been tremendous, and considers himself very lucky. For a film that wasn’t in any big festivals, did not have any big stars, and had a tiny marketing budget, he thinks they’ve done incredibly well, with a huge viewership on Amazon and Amazon Prime that helped push its revenue.

Tom hopes to make back-end money for his filmmaker services moving forward. However, since he took on just about all the marketing services for the film, from social media ad design and creation, to doing write-ups, and reaching out to countless media people among a million other things, he did build in a little bit of money (but not a lot) into the marketing budget to help compensate himself for the enormous amount of time and sweat put into it.

Things he would do differently include talking to different outdoor products more beforehand to see if they’d be willing to provide products and/or get involved in some way. After going to the Outdoor Retailers’ Market, there was interest in the film, but product placement or other tie-ins weren’t possible once the film was already in the can.

On his P&A spend, Tom had this to say:

Do I think if I had the money to spend more on social media ads, I would have spent more? I think I would for sure…I would expand our targeted audience wider, putting out different kinds of ads towards, say, older or younger audiences, or audiences who like indie Asian American films vs. outdoors films, as well as just pump more ads out to more people. I think there’s probably some point of saturation which we didn’t reach, and I think that would’ve upped our revenue. For us, though, after many months of huge success, we felt that we had gambled enough of my money and had to move on…all of this is still a gamble, so you need to know when to walk away at some point.

For a filmmaker who wanted to make a small film, with a bunch of people he knew and liked and who believed in the script, at a budget that meant he wouldn’t have to worry about waiting around to raise money or killing himself over a crowdfunding campaign, he achieved all of his goals. However, he doesn’t think he can keep making microbudget features and maintain his relationships and sanity.

But in the end, Tom realized his goals and dreams and even exceeded them, and what has happened with his film is beyond anything he could ever imagine, even in its relatively small scope. He knew he fully realized his dream when he got a post on social from a guy who told him he was watching the film while going through chemotherapy for cancer, and was so inspired by the film that he left the next day to go see Yellowstone and Bryce Canyon National Parks and sent Tom pictures.

It brought me to tears…I realized that this is why I want to make movies, to inspire people in a positive way. And that reward is way beyond going to Sundance or winning an Oscar… in that moment I really felt like I’d achieved my dreams as a filmmaker.

Tom’s advice to other filmmakers is to look at the big picture and do everything to scale, according to the kind of film you’re making and what assets you have to promote it. Independent filmmaking is all still a long game—a marathon, not a sprint.

The other film he was waiting on when this journey began is starting to gain traction again and they are hoping to secure a little bit of financing to start casting it. The film is called “Dealing with Dad” (Effie Brown is Executive Producing) and it is a dramedy feature about an Asian-American family dealing with depression. This past November they were lucky enough to be accepted into Film Independent’s Fast Track program, and then a week later won a pitch competition at an Asian-American Film festival.

We’ve been in touch with Tom quite a bit these last few weeks, and since people are basically shut inside at the beginning of the COVID crisis in in early April, 2020, and watching more streaming than ever, and he sent us this mini- case study as an update:

We decided to throw $200 for a weekend Facebook/Instagram ad run at our target audience to see if it made a dent. Since we saw that our highest viewership consistently was on a Sunday, we spent $200 for our ad to run Friday afternoon to Sunday afternoon (2 days). I’ve attached the kind of reactions we got from that 2-day run, plus our Facebook ad numbers so people can get an idea of the reach $100/day might be able to get. A .09¢/click average is okay, not amazing, but not bad (the lower the better). This ad run showed a corresponding rise in viewership of 50% on Amazon Prime for that weekend for us (can’t give out exact numbers, but it was a rise of the tens of thousands minutes viewed). I don’t think it’s a completely direct correlation, but it’s definitely part of the impact. So, the ads can definitely work if you find the right audience and make the right ad, I believe.

However, the problem is that since now that Amazon as of January 1, 2020 has lowered the base rev share they were offering from 6¢ to 1¢ per hour, any sort of gains we make on Amazon Prime are pretty negligible. Unless we get a crazy amount of viewership increase, or we somehow raise our CER, spending money on ads is basically spending more money to get back less. It’s pretty depressing, and we are how placing our hopes there might be some other outlet (AVOD??) that we’ll be able to push people to in the future that can actually help us.

Analysis by The Film Collaborative

Of course, one of the first things TFC would have mentioned in this section had Tom not beat us to it in what he wrote above: that a 1¢/hour rev share is an incredibly paltry and insulting amount to be offering filmmakers who pour their blood, sweat, and tears into making their films. But, it’s not like Amazon did not try to be an ally for the independent film community; their Film Festival Stars program was an incredible safety net and a great deal for some filmmakers, although Find Me wouldn’t have been eligible to participate because it didn’t have an A-list festival premiere. And, the fact that Festival Stars program was ended before even two years went by suggests the obvious: it’s hard to get most people to watch non-star- studded independent films. But there are AVOD Platforms where filmmakers are making real money, so if Amazon Prime cannot be the vehicle that will perform well for certain films, there are other platforms that can…for right now. Tubi is consistently mentioned by distributors as a rising star platform for revenue generation.

There are a couple of other things that still warrant a discussion, however, even as Tom was completely happy with the choices that he made to get his film where it ended up.

Regarding festivals, if Tom had come to us seeking help with a film festival strategy, we certainly would not have advised him to “go with the first film festival that accepted him.” (Let us pretend for just a moment that we are not currently living through a pandemic as we go to publish this case study, and that we are able to dispense advice that actually makes sense for the world we lived in before all the craziness, and that one day we will be able to live in again.) This is not to say that Tom’s choice of premiere didn’t work out for him—we would just like to provide some clarity on what we believe other filmmakers should be thinking about their premieres.

TFC’s co-executive director Jeffrey Winter has four basic questions that he asks when evaluating a possible premiere:

- Will the film Industry be taking notice?

- Will the film be getting domestic/international press (or at least more than local press)?

- Will other film festival programmers notice it in such a way that that it pays forward?

- Is the festival willing to pay a screening fee? Or, at least, travel and accommodations?

His basic philosophy is to perhaps overthink the festival to have as one’s premiere and then after that try to maximize exposure and not overthink too much, unless it is about which festivals would be the best to consider on a regional basis, since festivals in the same metropolitan areas tend to cannibalize each other.

As to Tom’s digital strategy, the fact that Indie Rights decided to launch solely on Amazon spurred quite a bit of internal discussion at TFC.

The majority of distributors seem to take a different approach. They put the film up everywhere it can possibly be placed so that viewers can watch the film the way they feel most comfortable. It also creates the impression that the film is getting a proper, robust release, which inspires confidence and signals that the film should therefore be taken seriously. It’s one of the reasons why many filmmakers have gone with Gravitas over the years, because they were very good at placing films on Cable VOD in the United States and Canada, which was much harder to do via a DIY-type aggregator. Nowadays, cable is not as important as it once was at the emergence of VOD, but certainly, there are distributors who still launch their digital releases by placing films on all the major TVOD platforms: iTunes (now AppleTV), Amazon, GooglePlay, and maybe Vudu, Microsoft, Sony, etc., at a bare minimum, and even some cable outlets.

So, knowing that one can do Amazon for free nowadays, the first question we asked ourselves was: What risk is Indie Rights assuming if all they are doing is putting the film up on Amazon? Furthermore, if this is the strategy that they use for all their films, is putting the film on Amazon merely a litmus test to see which films do any significant business before committing to placing films on GooglePlay and iTunes, which would incur actual and significant upfront costs? Many distributors recoup these fees from filmmaker earnings, but if there is nothing earned, there is nothing from which to recoup, so the distributor must eat those charges. It wasn’t so much that this strategy was a bad one—after all, TFC often advises filmmakers who have no more funds left to do Amazon and Vimeo yourself and see what happens, and if you still want to aggregate to iTunes and GooglePlay after a few months, we will be here for you—so much as the possibility there was a disconnect between what we wondered they might be doing, and what they actually told the filmmakers. Was there really a benefit to funneling their click-through targets to a single platform, and did they really have as much influence with Amazon because of their long history with the platform to justify this strategy? It made us wonder whether all their talk could be just a smokescreen.

We brought this up not just with Tom Huang, who had no real reason to doubt them, but also with Linda Nelson of Indie Rights to try to drill down a bit further into why they thought an Amazon-only strategy worked for them. Linda reiterated the reasons they preferred Amazon over iTunes for films that do not have an obvious commercial value. But the discussion regarding Amazon bled into Indie Rights’ longstanding relationship with them and the fact that one could transition to SVOD and also quite easily release films in international territories, and in fact more international territories than an individual could do on his or her own. We felt that although that approach completely made sense to us, we also had to admit that we often never really know how much influence a distributor has with a platform in terms of placement, and that Indie Rights was no exception in this case.

We could not deny that to make this much money on TVOD and then SVOD was not the norm, in the sense that TFC has rarely seen similar films—the kind without festival pedigree or named cast—do as well as Tom’s has. We certainly can’t and don’t claim that we have a sufficient number of films that are performing well enough in our Digital Distribution program to have Amazon’s ear about placement on the platform. But this is a shining star for Indie Rights as well. There’s a reason Indie Rights pushed for this film to be the subject of one of our case studies: it’s a success story. If Indie Rights was able to achieve this result simply because of their relationship and experience with this specific platform, then surely they could reproduce these results with all of their titles, which is not the case, though this film is not their only success story, either (Indie Rights explained that Amazon is best suited to distribute and monetize low-budget films with a budget under $500,000 – and for those films, the revenue generated pays off). In the end, we still had a few nagging questions, such as why one would begin an iTunes window four months after their SVOD window started and not sooner, and, why couldn’t they release the film on all three main TVOD platforms but target only Amazon with their ads?

Distributors by definition have more experience than filmmakers. They claim that they have influence all the time. In the case of Indie Rights, a big selling point of theirs is that they have a booth at the Cannes Marché du Film and do the American Film Market (AFM) in Los Angeles, so that they are in a great position to handle worldwide sales. Tom even quoted this line back to us when discussing their availability to get back to them about how their film is doing on the platforms. But in this case, their theatrical/digital release was May 31, right after Cannes, so the timing wasn’t right for that year. Plus, they launched on Amazon Prime in that enhanced list of international territories in mid-July, so clearly, they did not think international was worth holding back until after AFM in November. And when we look at the TVOD and SVOD numbers, only 1-2% of the earnings come from the U.K. and the rest of the world. Which means that for all the talk Indie Rights did about maximizing worldwide revenue potential, in the end, for Find Me, it didn’t make much of a difference.

But we cannot dismiss Indie Rights’ relationship with Amazon that easily. We also have had lots of filmmakers try to do Facebook ads, and create partnerships, and work with PR films, and try just as hard as Tom did for people to take notice. Even a little help on the platform side can start the ball rolling, and without that, one may not get off the ground. But without Tom putting in so much work of his own in terms of marketing, placement alone might not have worked as well as it did. We tell all indie filmmakers that no one is going to market your film better than you, and this was certainly the case in this instance as well.

The third factor in this sort of perfect storm trifecta is the fact that people undeniably responded to Tom’s film. He had almost built a gestalt around it, where people would not just rent it—as in, shell out money for it, which ordinary people seem to do less and less of these days for a film that doesn’t have a star power—but take the extra step of recommending it to their friends. This is the sort of X-factor that successful films need to possess in order to do well. A lot of filmmakers think their films have it, but actually don’t. In all the hundreds and hundreds of films that The Film Collaborative has handled in the past ten years, and as much as we personally may love some of them, only a small percentage of them have had this quality. It takes on a life of its own in a way that defies its actual on-paper pedigree.

TL;DR

While TFC was left with some questions on this digital blueprint, it’s hard to deny that Tom’s and Indie Rights’ strategies were successful in this case. Next time, we would advise Tom to ask a few more questions when a strategy seems out of keeping with industry standards, and to take a more calculated approach to festivals (especially the premiere). However, Tom did a lot of things right: he set realistic goals and expectations, targeted his marketing budget at a specific and reachable demographic, paid attention to his social media statistics, utilized his social connections where appropriate, and was realistic about his own limits around how much time/effort he could spend on distributing a project before he had to get back to filmmaking. Tom’s film is on track to be in the black next quarter, and he connected with his audience beyond their wallets—which we always count as a success. At the end of the day, the biggest takeaway is that he made more money from distribution than he would have from going with an all-rights or VOD-only distributor, who most certainly would have taken more fees and recouped more in costs.